6 Epistemology

This chapter is a detailed case study of epistemology articles in the twelve journals. I’m including this partially for self-interested reasons: I work in epistemology and I wanted to see what the field looked like. But I’m also including it because the data here makes a striking point.

- Main Thesis

- The literature on the Gettier problem is not that big.

Now I don’t mean to say it’s small. There is a plausible case that it is (or at least was circa 2013), the largest sub-iterature within epistemology. And for a while it was a huge proportion of what goes on in epistemology. But that time has passed, and I suspect a lot of people haven’t updated their view of the field.

Within these twelve journals, the literature on the Gettier problem consists of roughly one hundred articles. That’s a third of a percent of all the articles in those journals. And given the importance of the question it addresses, What is knowledge?, a third of a percent seems fine to me. I think it’s a widespread view in philosophy that the Gettier problem literature was much bigger than it should have been. And I think that’s false; a third of a percent is a perfectly reasonable proportion of the available journal space.

To analyze the epistemology literature, it would help to know what the epistemology articles are. Since I’ve already said that I’m treating four topics—the larger half of arguments, knowledge, justification, and formal epistemology—as the epistemology topics, one might think the thing to do would be to just take articles from those topics. But this doesn’t work for a couple of reasons. In theory, which topic has the highest probability isn’t that significant. Whether an article’s highest probability is in one of the epistemology topics depends on just how the model carves up the space of nonepistemology topics, and that seems wrong. In practice, this method declares that “Is Knowledge Justified True Belief?” (Gettier 1963) is not an epistemology article, and that isn’t something we can live with.

A better approach is to sum the probabilities that the model gives to an article being in one of the four epistemology topics, call that its epistemology probability, and then say that an article is an epistemology article if its epistemology probability is above a threshold. But where should the threshold go? Since I want to convince readers that the Gettier problem literature isn’t that big, I want to have a very inclusive definition of epistemology, so I capture all the articles in that literature. So that militates in favour of a low threshold.

There is also the fact that epistemology articles tend to naturally slide into a lot of different topics. If they discuss scepticism at all, the model thinks they might be talking about Hume. If there is any probability talk, the model thinks they might be doing theory of confirmation or theory of chance. If they talk about which propositions a subject does or doesn’t know, the model thinks they might be talking about propositions. If they talk about values, or norms, or obligations, or permissions, the model thinks they might be doing ethics. And the house style of Anglophone epistemology is close enough to the style of the ordinary language philosophers that the model constantly thinks they might be just ordinary language philosophers.

Which is all to say that the cut-off ended up being much lower than I expected. I ended up setting it at just 0.2. This seems absurd, but rather than doing the pure theory, let’s look at what this looks like in practice. Here are the last eight articles that are classified as epistemology under this measure (i.e., the eight articles with a probability of being epistemology just above 0.2).

- Kirk Ludwig, 1992, “Skepticism and Interpretation,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 52:317–39.

- Cindy D. Stern, 1990, “On Justification Conditional Models of Linguistic Competence,” Mind 99:441–5.

- Catherine J.l. Talmage and Mark Mercer, 1991, “Meaning Holism and Interpretability,” The Philosophical Quarterly 41:301–15.

- David E. Nelson, 1996, “Confirmation, Explanation, and Logical Strength,” British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 47:399–413.

- Richard Schantz, 2001, “The Given Regained. Reflections on the Sensuous Content of Experience,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 62:167–80.

- N. M. L. Nathan, 2004, “Stoics and Sceptics: A Reply to Brueckner,” Analysis 64:264–8.

- Hastings Berkeley, 1912, “The Kernel of Pragmatism,” Mind 21:84–8.

- Michael Martin, 1973, “The Objectivity of a Methodology,” Philosophy of Science 40:447–50.

Those aren’t all epistemology articles, but some of them are. The Ludwig clearly is, and the Nathan, and plausibly several others. What about the eight that just missed the cut (i.e., the ten with a probability of being in epistemology just below 0.2).

- Irving Thalberg, 1974, “Evidence and Causes of Emotion,” Mind 83:108–10.

- Sanford C. Goldberg, 2000, “Word-Ambiguity, World-Switching, and Semantic Intentions,” Analysis 60:260–4.

- James Van Cleve, 1992, “Semantic Supervenience and Referential Indeterminacy,” Journal of Philosophy 89:344–61.

- Alvin Plantinga, 1998, “Degenerate Evidence and Rowe’s New Evidential Argument from Evil,” Noûs 32:531–44.

- Curtis Brown, 1992, “Direct and Indirect Belief,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 52:289–316.

- Elazar Weinryb, 1978, “Construction vs. Discovery in History,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 39:227–39.

- Robert K. Shope, 1973, “Remembering, Knowledge, and Memory Traces,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 33:303–22.

- David E. Cooper, 1977, “Lewis on Our Knowledge of Conventions,” Mind 86:256–61.

That’s pretty good—we don’t seem to be excluding any articles that should be included. So the threshold is at 0.2.

The result of all this is that we get 1842 articles to work with. They are not distributed evenly across the years, to put it mildly. Here is how many articles there are in each year.

Figure 6.1: Number of epistemology articles each year.

The gaps are for the cases where there are zero papers. Through 1945, there are only twenty-four papers. So from now on I’m going to start graphs after World War II. And I’m not going to divide things up into journals; I am not going to use up space with a graph that shows that Philosophy and Public Affairs doesn’t publish much epistemology. But those twenty-four papers will stay in the analysis; I just won’t present them on graphs.

The next step was to take the 1842 articles and, as one might have guessed, build an LDA model for them. After a little bit of trial and error, I decided to set the number of topics to forty. I wanted to get the number to be as small as possible, while still having a topic that in some plausible sense had only Gettier problem papers.

It divided the 1842 papers up into the following forty subjects. The subject column is my subjective description of what area the papers there seem to be about. The count column is how many articles are in that subject (i.e., the model gives more probability to them being in that subject than it gives to any other subject). The weighted count is the expected number of articles in that subject (i.e., the sum across all articles of the probability of the article being in that subject). And the year column is the average publication date of the papers that are in the subject. I’ve renumbered the topics so they are arranged by year.

| Topic | Subject | Count | Weighted Count | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Knowledge of mind | 82 | 77.53 | 1968.0 |

| 2 | Ordinary language | 73 | 81.70 | 1972.7 |

| 3 | Statistics | 44 | 51.44 | 1979.3 |

| 4 | Surprise exam | 40 | 35.64 | 1983.2 |

| 5 | Belief | 78 | 100.34 | 1983.3 |

| 6 | Gettier | 103 | 90.92 | 1983.9 |

| 7 | Conditionals | 123 | 106.51 | 1983.9 |

| 8 | Scepticism | 34 | 45.31 | 1988.4 |

| 9 | Evidence | 37 | 45.15 | 1988.8 |

| 10 | Know-how | 65 | 59.23 | 1988.8 |

| 11 | Rationality | 42 | 49.36 | 1988.8 |

| 12 | Degree of belief | 29 | 32.54 | 1989.3 |

| 13 | Logic and paradoxes | 49 | 50.60 | 1990.4 |

| 14 | Assertion | 37 | 31.38 | 1990.8 |

| 15 | Virtue | 35 | 32.13 | 1990.9 |

| 16 | Experts | 37 | 28.34 | 1991.2 |

| 17 | Infinity and regresses | 30 | 32.63 | 1992.3 |

| 18 | Skepticism | 61 | 57.43 | 1992.4 |

| 19 | Perception | 69 | 81.10 | 1992.7 |

| 20 | Conditionalisation | 72 | 64.35 | 1993.0 |

| 21 | Deception | 51 | 45.98 | 1993.5 |

| 22 | Ethics of belief | 52 | 50.77 | 1994.4 |

| 23 | Semantic externalism | 48 | 48.94 | 1994.7 |

| 24 | Processes | 27 | 31.45 | 1995.1 |

| 25 | Preferences | 21 | 21.01 | 1996.0 |

| 26 | Decision theory | 22 | 25.67 | 1996.1 |

| 27 | Triviality results | 41 | 40.45 | 1997.0 |

| 28 | Desires | 29 | 27.20 | 1997.1 |

| 29 | Aim of belief | 43 | 40.57 | 1997.2 |

| 30 | Epistemic value | 37 | 35.01 | 1997.6 |

| 31 | Transmission | 30 | 33.20 | 1998.6 |

| 32 | Testimony | 36 | 33.29 | 1998.9 |

| 33 | Luck | 46 | 53.48 | 1999.9 |

| 34 | Bootstrapping | 31 | 22.01 | 2000.9 |

| 35 | Epistemic modals | 23 | 21.47 | 2001.5 |

| 36 | Contextualism | 58 | 50.76 | 2002.1 |

| 37 | Sleeping beauty | 49 | 47.21 | 2004.6 |

| 38 | Assertion | 20 | 23.00 | 2005.6 |

| 39 | Disagreement | 21 | 17.53 | 2007.0 |

| 40 | Accuracy | 32 | 34.37 | 2007.3 |

There are several weirdnesses here that are worth listing. (I don’t think this eliminates the usefulness of the model, but I should be up front about the shortcomings.)

- The larger LDA had put epistemic modals in with epistemology (reasonably enough), then followed that up by putting indicative conditionals in as well. Indicative conditionals are a tricky subject to classify, and different models treated them differently. But given their links to work on probability, and to epistemic modals, it isn’t surprising they end up in epistemology. Still, it means topic 7, and topic 36, are more philosophy of language topics than epistemology.

- Similarly I could easily put topic 19 (perception), and even topic 1 (knowledge of minds), in philosophy of mind. I’m working in this chapter with a fairly broad conception of epistemology.

- I don’t know why this model split topics 14 and 38, which both look like norms of assertion. I think what’s going on is topic 14 is pre-Williamsonian and topic 38 is Williamsonian. But it does look a bit like a pretty arbitrary split.

- I do know what’s going on with topics 8 and 18, and it’s a little hilarious. The model just does string recognition, so it doesn’t know that ‘sceptic’ and ‘skeptic’ are stylistic variants. But it does know they are super important words. So each of them gets its own topic.

- Splitting off topic 16 (experts) from topic 32 (testimony) was a bit weird.

- Topic 24 includes both process reliabilism work, and work from recent cognitive science on mental processes. This isn’t terrible, but it’s not how I would have carved things up.

- I’ve called topic 4 the surprise Exam, but there is also a lot of work here on the sly Pete example. I’m not entirely sure what the model saw that put these puzzles together.

In the remaining sections of this chapter I include (automatically generated) statistics, graphs, keywords and key papers from these topics, so readers can investigate them more at leisure. For now I want to talk about the broad trends, some highlights, and then especially topic 6 (Gettier).

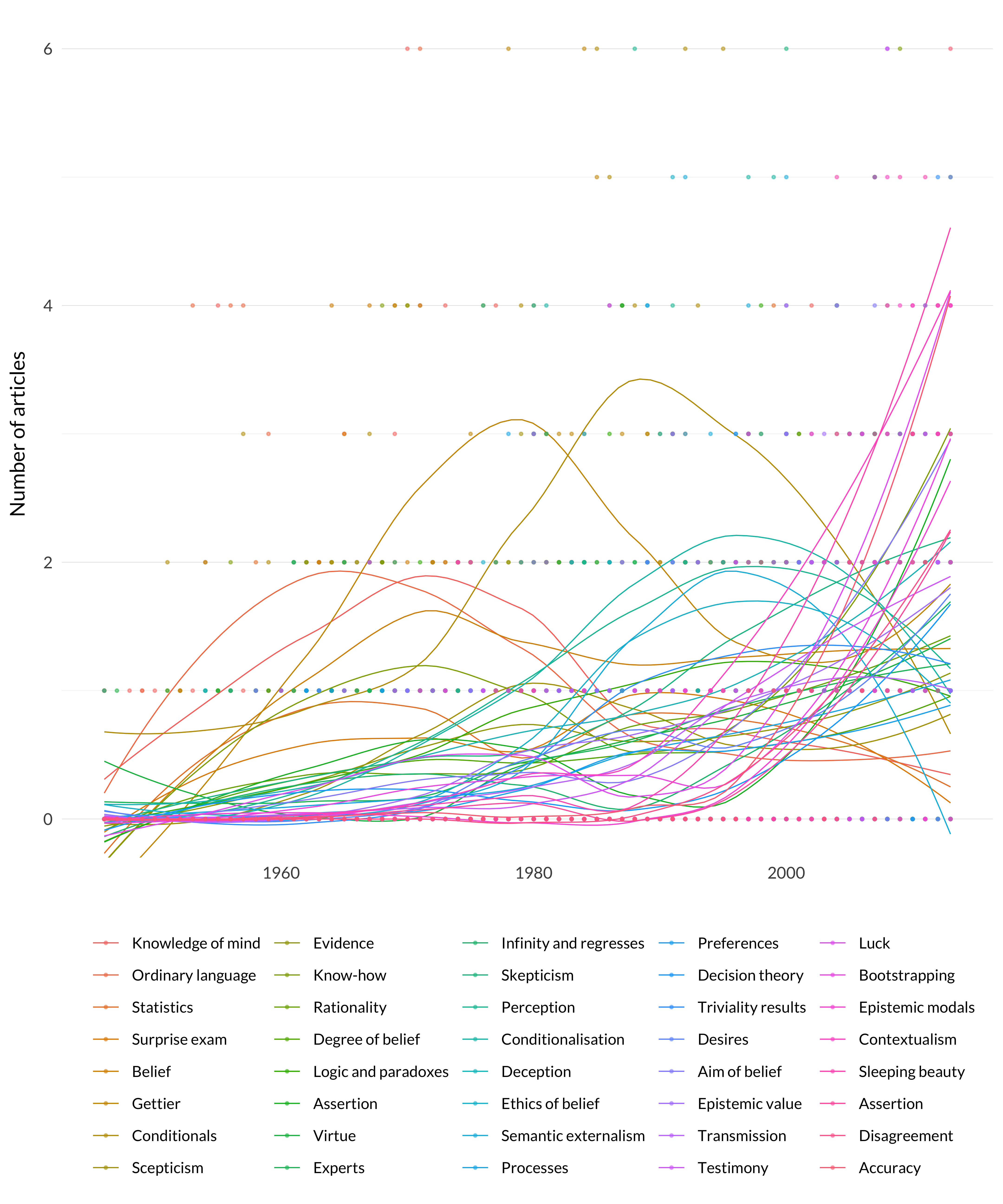

First are the overall graphs of the raw count and the weighted count. I’ve included trend lines for the raw count because otherwise there are a lot of overlapping dots. And I’ve capped the graph at 6 to make everything clear.

Figure 6.2: Number of articles in each epistemology topic.

The “missing” data points are:

| Year | Subject | Count |

|---|---|---|

| 1996 | Perception | 8 |

| 2005 | Contextualism | 10 |

| 2006 | Testimony | 7 |

| 2010 | Contextualism | 8 |

| 2012 | Accuracy | 9 |

These points are not shown, but they are influencing the curves.

The graph is a lot of stuff, but the basic picture is fairly straightforward.

The Gettier problem was a big deal through the late 1970s and early 1980s. It’s perhaps worth noting here that the model treats work on Nozick’s theory of knowledge as part of the Gettier problem literature, which is fair enough, and it explains a bit of its longevity. Then there is a bunch of work on conditionals. Then a lot of modern topics become significant, and several of them seem to be as significant to the philosophical literature in the 2010s as the Gettier problem was in the 1970s.

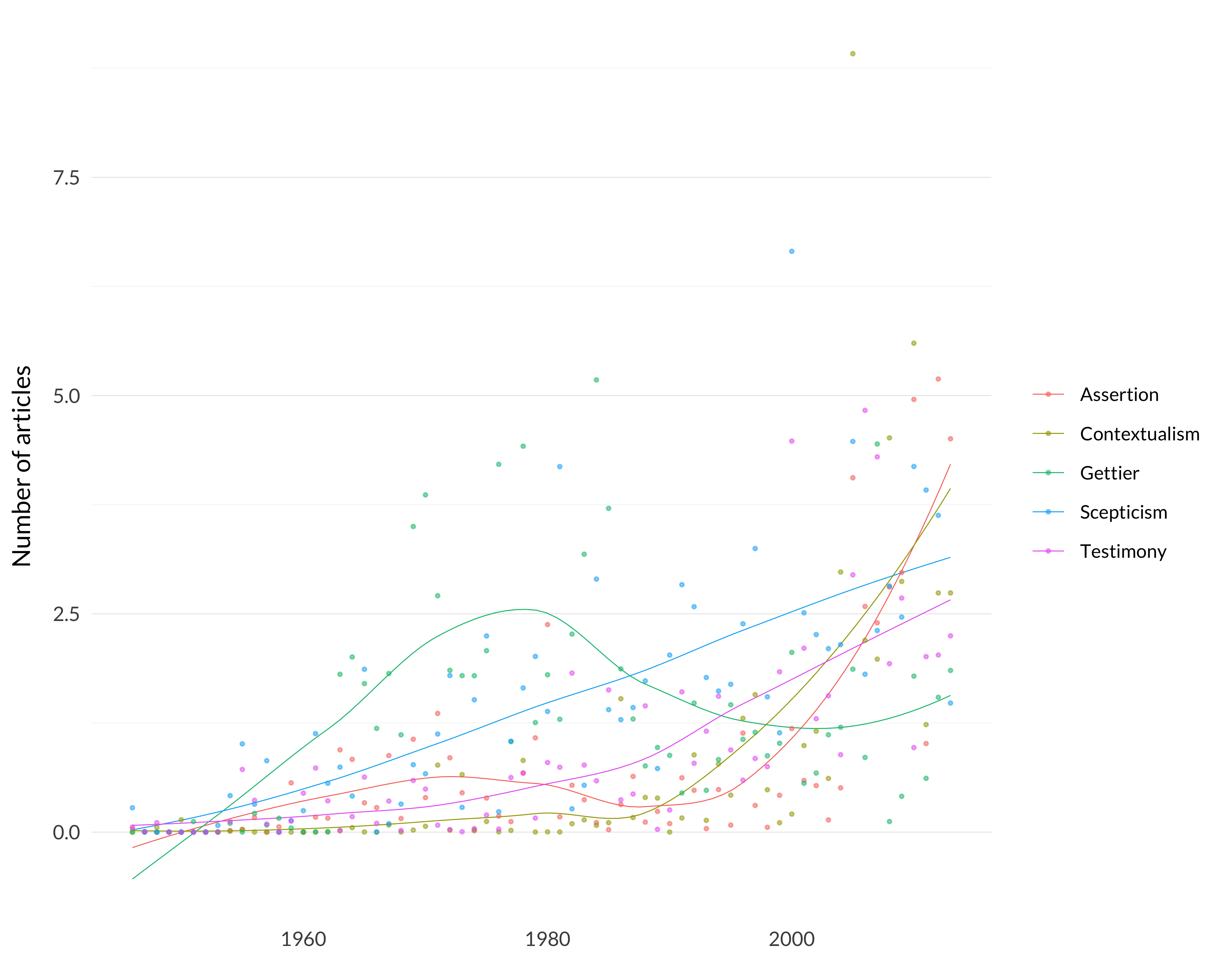

The picture doesn’t change enough if we use weighted counts rather than counts, though this does let us remove the trendlines.

Figure 6.3: Weighted number of articles in each epistemology topic.

In this case there are just two missing data points.

| Year | Subject | Weighted Count |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Contextualism | 8.915284 |

| 2012 | Accuracy | 8.666790 |

It’s much easier to see what’s happening here with the subjects separated out. Again, I’ve left off those two data points so they don’t throw off the scale of the whole graph.

The model makes these three weird divisions: splitting experts from testimony, having two assertion categories, and dividing skepticism and scepticism. Let’s put those together, alongside the two big topics from theory of knowledge: contextualism and Gettier.

Figure 6.4: Five epistemology categories.

I think that gives a pretty good sense of what the central parts of epistemology have looked like over the last fifty or so years. The Gettier problem was the central question, for a while by far the central question. (Note that the loess curve here is well under some of the dots, so it understates the trend.) But scepticism keeps being taken more and more seriously, even if still as something haunting the land. But issues about language, and about social epistemology, are now as important as the Gettier problem ever was.

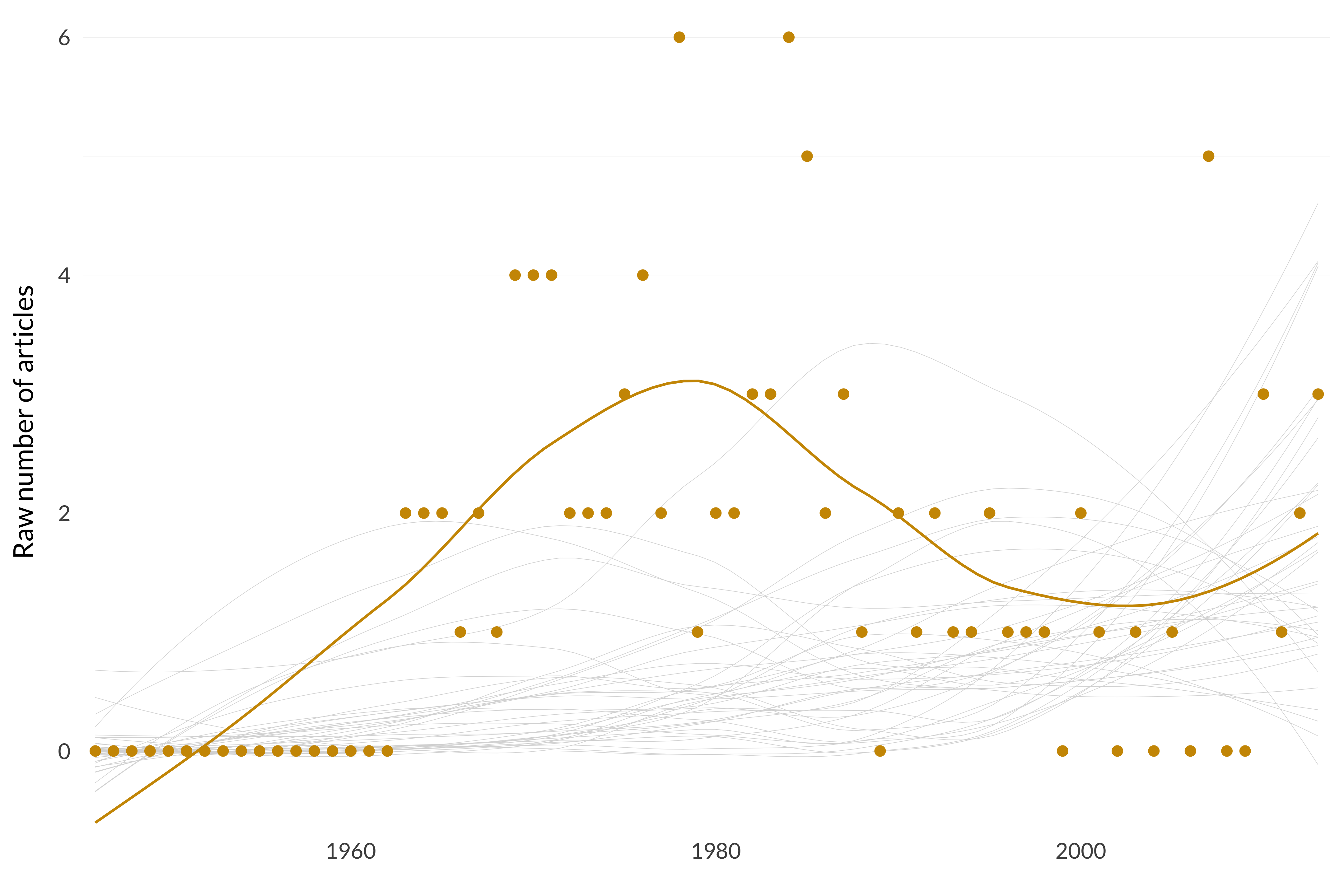

So why was the Gettier problem so widely thought to be dominating epistemology? The following four graphs might help explain this perception. I’ll eventually do these for each of the 40 topics, though I won’t include any commentary on any of them other than these. First, here’s the graph (with trendline) of the raw number of articles about the Gettier problem each year.

Figure 6.5: Number of articles in topic 6, Gettier.

There were a few articles, especially in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but it doesn’t look so huge. It’s even less dramatic if using weighted counts.

Figure 6.6: Weighted number of articles in topic 6, Gettier.

We can also look at that as a percentage of all philosophy articles published in that year.

Figure 6.7: Percentage of philosophy articles that are in topic 6, Gettier.

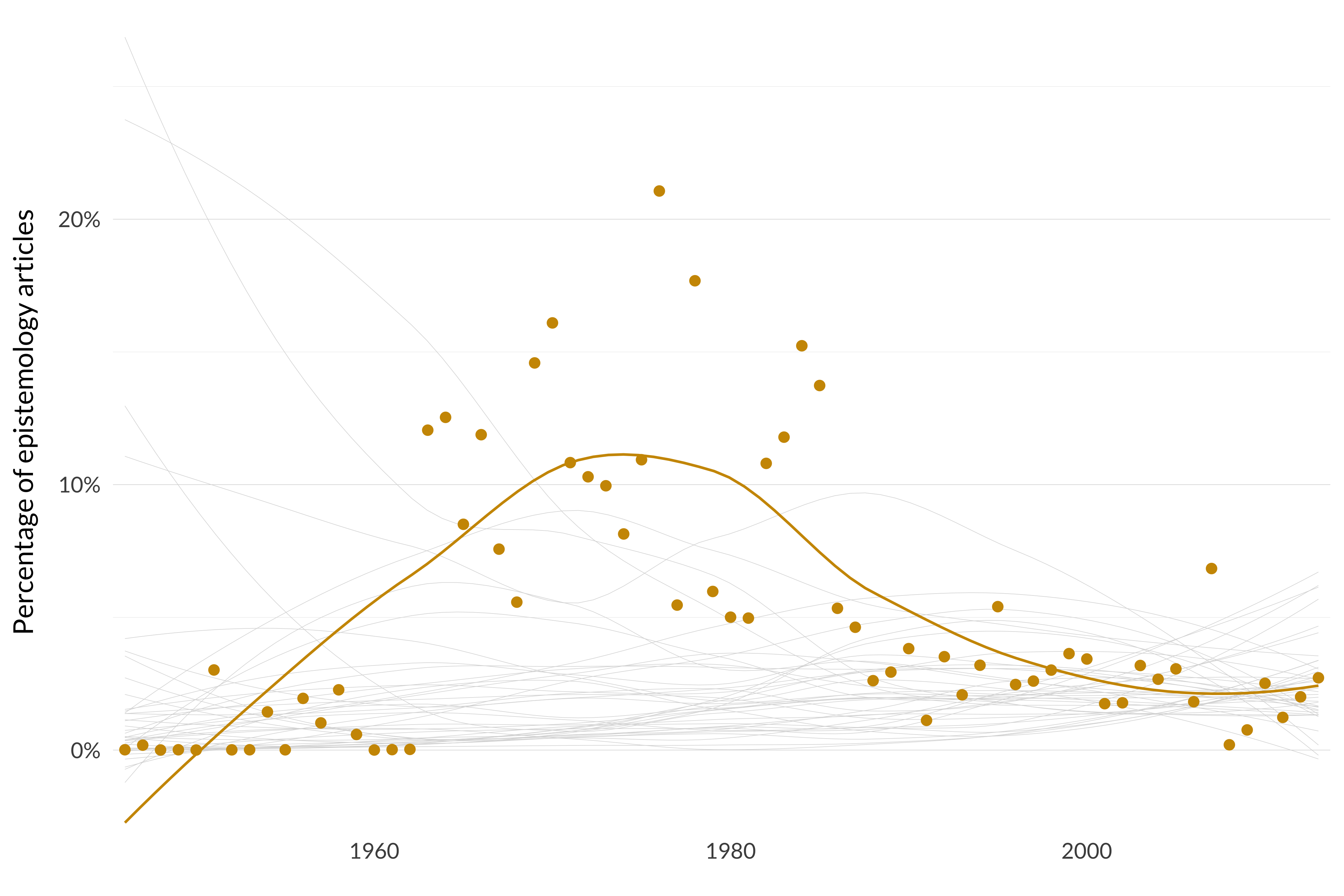

At its height, it’s about 1.3 percent of all the philosophy being done in a year. That’s not a small number, but there are only four years where it is above 1 percent, and only four more between 0.75 percent and 1 percent. So why is it remembered as taking over everything? This graph I think is part of the explanation. Now we’ll express these articles as a percentage of all epistemology being published.

Figure 6.8: Percentage of epistemology articles in topic 6, Gettier.

Characteristic Articles

- Gilbert H. Harman, 1966, “Lehrer on Knowledge,” Journal of Philosophy 63:241–7.

- John A. Barker, 1975, “A Paradox of Knowing Whether,” Mind 84:281–3.

- Peter D. Klein, 1979, “Misleading”Misleading Defeaters”,” Journal of Philosophy 76:382–6.

- James G. Mazoue, 1985, “Nozick on Inferential Knowledge,” The Philosophical Quarterly 35:191–3.

- Edmund L. Gettier, 1963, “Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?,” Analysis 23:121–3.

- Peter D. Klein, 1976, “Knowledge, Causality, and Defeasibility,” Journal of Philosophy 73:792–812.

- David Coder, 1970, “Thalberg’s Defense of Justified True Belief,” Journal of Philosophy 67:424–5.

- John Turk Saunders and Narayan Champawat, 1964, “Mr. Clark’s Definition of ‘Knowledge’,” Analysis 25:8–9.

- Graeme Forbes, 1985, “Response to Mazoue & Brueckner,” The Philosophical Quarterly 35:196–8.

- Keith Lehrer and Thomas Paxson, Jr., 1969, “Knowledge: Undefeated Justified True Belief,” Journal of Philosophy 66:225–37.

Highly Cited Articles

- Edmund L. Gettier, 1963, “Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?,” Analysis 23:121–3. (0.9676315)

- Keith Lehrer, 1965, “Knowledge, Truth and Evidence,” Analysis 25:168–75. (0.9015168)

- Michael Clark, 1963, “Knowledge and Grounds: A Comment on Mr. Gettier’s Paper,” Analysis 24:46–8. (0.8368709)

For several years it was 15 to 20 percent of all epistemology that was being published. And remember that we have a very inclusive conception of epistemology, so there’s a decent case that these numbers are on the low side, and it’s really more like 20 to 25 percent. And that does seem excessive. So there’s a reasonable case that for a while the Gettier problem literature was a rather excessive proportion of the epistemology literature. And maybe that’s why it looms so large in a lot of people’s impressions of what happens in epistemology.

The rest of this chapter is automatically generated. Every section covers one of these forty topics. It displays:

- The keywords for each topic.

- The raw and weighted counts of articles in that topic.

- The four graphs I just showed.

- The ten articles that have the highest probability of being in that category. (These aren’t weighted by length, because so many of the significant articles are short.)

- If there are any of the six hundred highly cited articles, it includes those as well.