4.7 Philosophy of Language

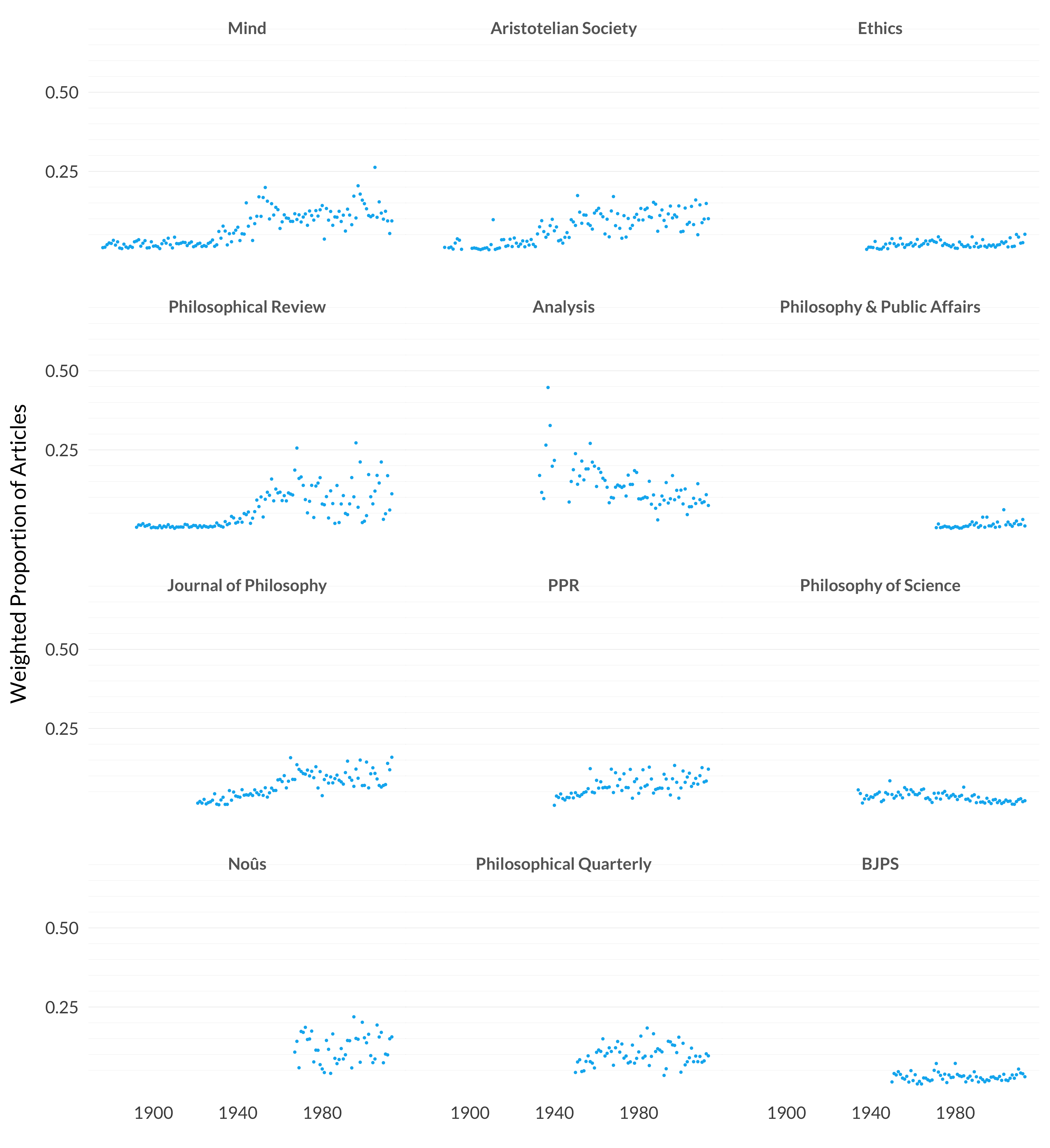

Figure 4.18: Proportion of each journal’s yearly publications in Philosophy of Language

There isn’t much trend there. Within Analysis I guess there is a downward trend, though it’s so random before its wartime hiatus that it’s hard to say. Philosophical Review starts publishing philosophy of language articles in the 1940s then especially in the 1950s. (This is probably connected to Norman Malcolm moving to Ithaca.) Afterwards there is a bit of year-to-year variation, largely because the Review publishes so few articles. Before Ryle takes over there isn’t a lot of philosophy of language in Mind, then it is fairly steady apart from a blip upward in the 1990s. But otherwise there isn’t much trend here to speak of. Let’s instead look at the topics.

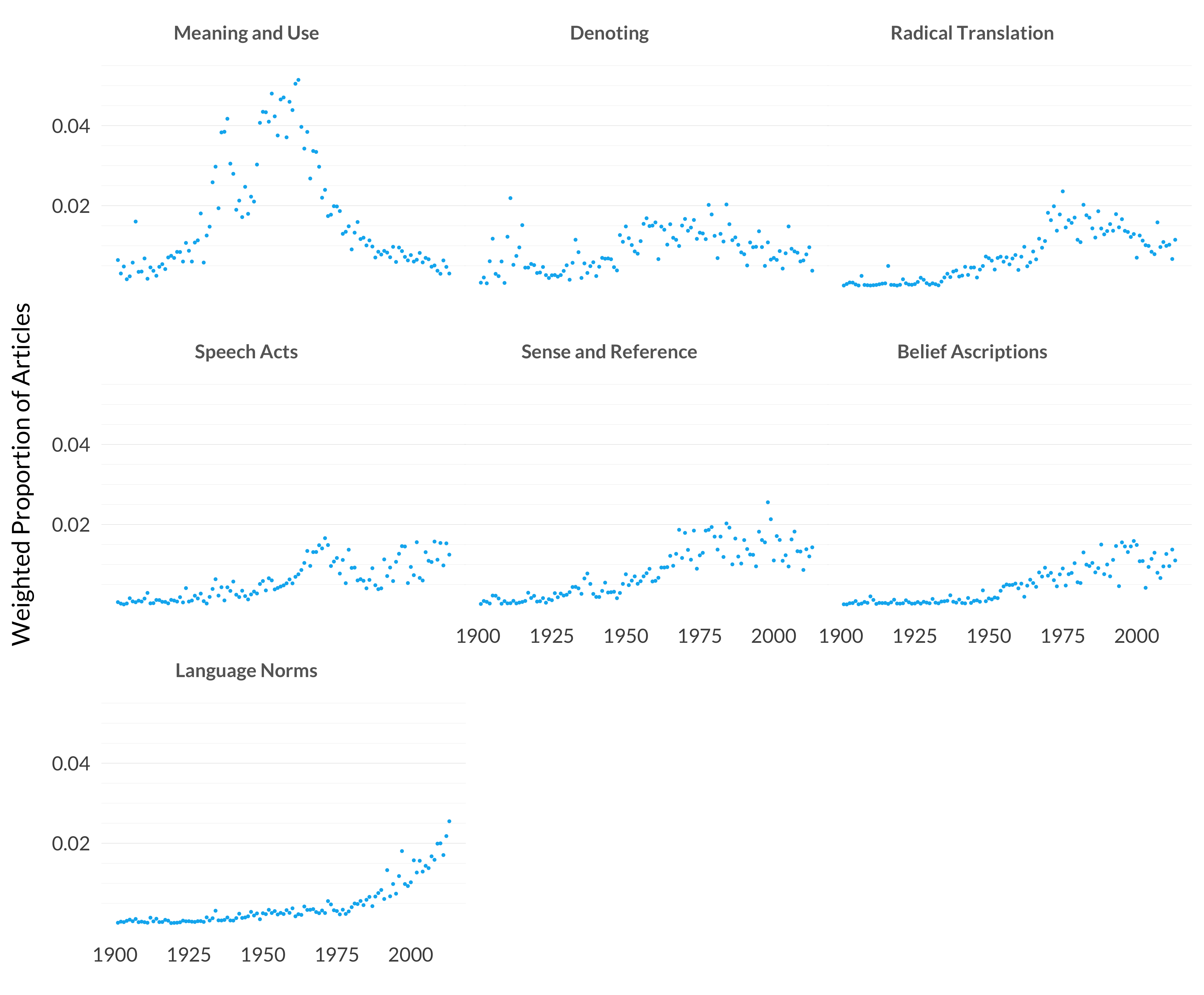

Figure 4.19: Topics in Philosophy of Language

That’s more interesting. Four of the topics are almost absent before 1940. A fifth, centered around On “Denoting“, has a flurry of early century activity, then picks back up again in the 1950s. All five of them continue to be important to the present day, though a few of them look slightly down from their peaks.

But the dominant theme here is Wittgensteinian philosophy of language. It has a remarkable rise and then an equally remarkable fall. What surprises me is how much work on this topic the model finds pre-1900. It could just be noise—we’re talking at most 2 percent of a small number of articles. But the model doesn’t think that Fregean or Quinean philosophy of language turns up in these articles, so it’s a bit interesting that it sees some Wittgensteinian work there.

The rise and fall of Wittgensteinian philosophy of language is not symmetric. The rise took away from other parts of philosophy, but when the fall happened the interest simply shifted to other areas in philosophy of language. The result was that philosophy of language was stronger afterward than before, though the work that ended up being central was not the work that made philosophers take philosophy of language seriously.

There would be more topics here, and the overall graph would trend more sharply upwards, except the model itself thought that some topics that could have been in philosophy of language are better placed in logic and mathematics. I’ll come back to that in the next chapter.