2.74 Knowledge

Category: Epistemology

Keywords: knowing, knows, skeptic, skeptical, knowledge, edge, testimony, warranted, know, warrant, skepticism, closure, williamson, hands, epistemology

Number of Articles: 426

Percentage of Total: 1.3%

Rank: 21st

Weighted Number of Articles: 416.2

Percentage of Total: 1.3%

Rank: 23rd

Mean Publication Year: 1990.8

Weighted Mean Publication Year: 1980.7

Median Publication Year: 1997

Modal Publication Year: 2005

Topic with Most Overlap: Justification (0.0734)

Topic this Overlaps Most With: Justification (0.0603)

Topic with Least Overlap: Chemistry (0.00041)

Topic this Overlaps Least With: Space and Time (0.00102)

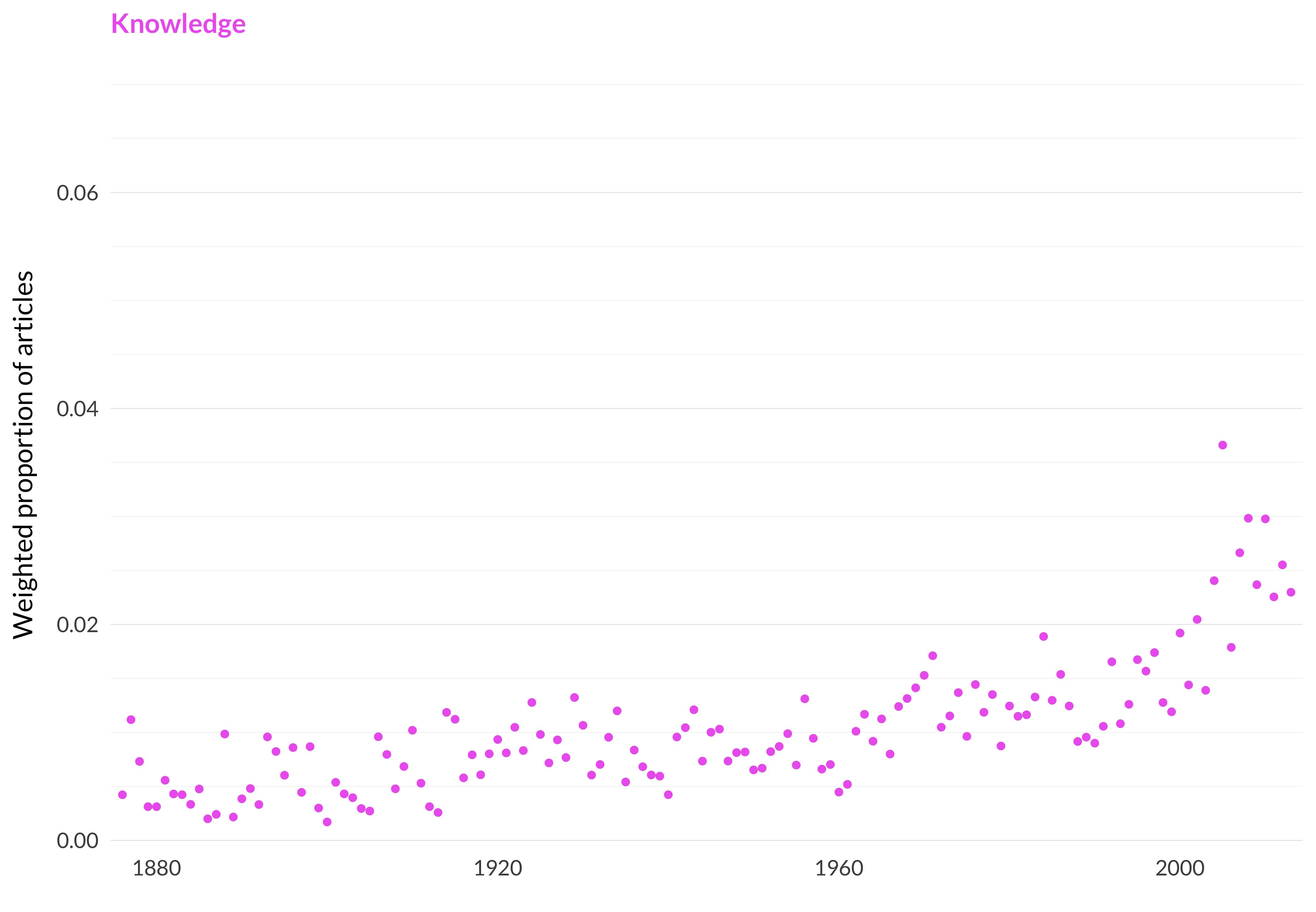

Figure 2.171: Knowledge.

Figure 2.172: Knowledge articles in each journal.

Comments

It’s perhaps a bit surprising that theory of knowledge—everything from scepticism to Gettier cases to testimony to closure principles to Williamsonian knowledge-first epistemology—is in just one topic. And that it’s just 1.3 percentof all the articles.

In part this is because of how new a topic it is. There just isn’t very much that feels like contemporary epistemology from before World War II. Of the 426 articles in this topic, only six of them are between World War II. And five of those feel like fairly borderline cases, where the model couldn’t really make up its mind. There is one notable exception.

| Subject | Probability |

|---|---|

| Knowledge | 0.4428 |

| Deduction | 0.1234 |

| Perception | 0.1125 |

| Idealism | 0.1118 |

| Methodology of science | 0.0433 |

| Truth | 0.0332 |

| Meaning and use | 0.0295 |

| Justification | 0.0221 |

I couldn’t find any other references to Dhirendon Mohon Datta, but that’s a typo. (Or a nonstandard transliteration.) Dhirendra Mohan Datta wrote a number of books. (The details about Datta that follow are from sources that I was pointed to in helpful conversations with Michael Bench-Capon, Bryce Huebner and Michael Kremer.)

He wrote The Philosophy of Mahatma Ghandi (Dhirendra Mohan Datta 1953), based on his time working with Ghandi.

He also wrote The Six Ways of Knowing: A Critical Study of the Vedānta Theory of Knowing (Dhirendra Mohan Datta 1960), which overlaps with this paper. Indeed, on page 337 of the second edition of that book, he refers to “Testimony as a Method of Knowing” as his article. (Thanks to Michael Bench-Capon for spotting this.) I’ve linked to the second edition, which is the only one I could find online. If the first edition is like the second, it would be decades ahead of its time. (And the Mind article suggests that that’s true.)

And he coauthored a prominent textbook: An Introduction to Indian Philosophy (Chatterjee and Datta 2007).

When he retired, Datta’s colleagues and students put together a festschrift for him, which is available through the Internet Archive: World Perspectives in Philosophy, Religion and Culture (Singh 1960). These books normally have a somewhat detailed biography of the honoree, but this one only has a skimpy four-page stub. Still, we learn something interesting from it. Most of the Indian philosophers who published in Mind and Philosophical Review in the first half of the century spent a fair bit of time in Britain or United States.14 Datta did not; he acquired his very extensive knowledge of philosophy in England from his teachers (especially his brother) and his own reading.

There is a really interesting book to be written about the ways in which late twentieth-century English language philosophy resembles (some strands in) Indian philosophy more than it resembles early twentieth-century English language philosophy. And Datta could be a key part of that story. But that’s for another book and, preferably, an author with more knowledge of Indian philosophy than I have. So I’ll leave Datta here for now.

I’ve written much more on postwar epistemology in chapter 6. The main takeaway from the longer chapter is that work on “Gettier cases” makes up a surprisingly small amount of the work in epistemology. It does make up a large percentage of the work in epistemology in the early years. (And for epistemology, the early years extend into the 1980s.) But it’s never as big a percentage of work done in philosophy as I suspect a lot of people believe.

Datta also had an invited paper in Philosophical Review.↩︎