2.5 Dewey and Pragmatism

Category: History of Philosophy

Keywords: dewey, pragmatism, judgment, objectivity, judgments, relativism, objective, objectively, inquiry, subjective, ideal, peirce, judged, situation, ments

Number of Articles: 256

Percentage of Total: 0.8%

Rank: 61st

Weighted Number of Articles: 380.2

Percentage of Total: 1.2%

Rank: 30th

Mean Publication Year: 1949.9

Weighted Mean Publication Year: 1954.6

Median Publication Year: 1950

Modal Publication Year: 1951

Topic with Most Overlap: Value (0.045)

Topic this Overlaps Most With: Moral Conscience (0.0365)

Topic with Least Overlap: Belief Ascriptions (0.00028)

Topic this Overlaps Least With: Races and DNA (0.00144)

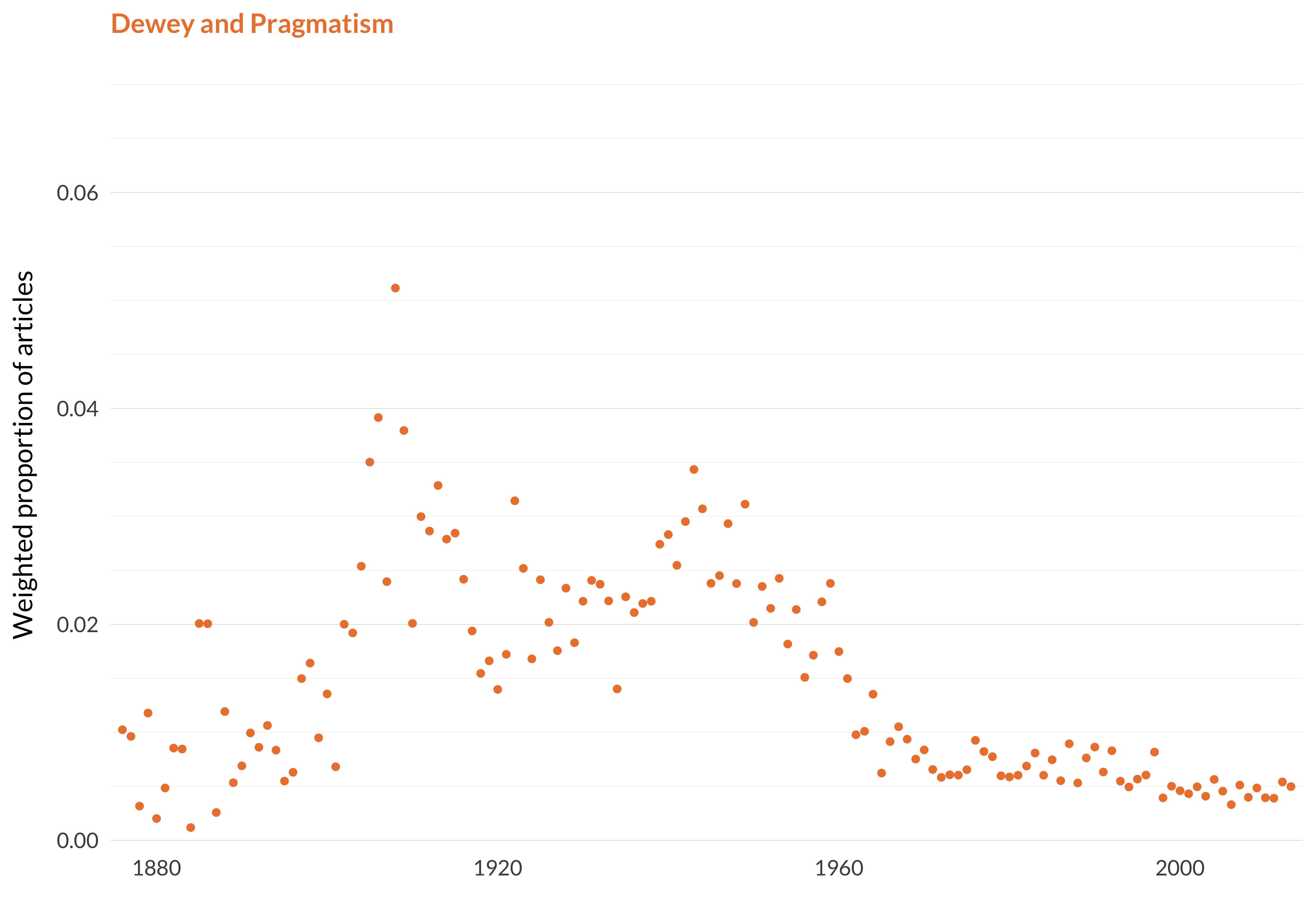

Figure 2.12: Dewey and pragmatism.

Figure 2.13: Dewey and pragmatism articles in each journal.

Comments

One of the disappointing things about this model was how it handled pragmatism. Most model runs ended up with a very nice pragmatism topic, that gave a very clear sense of the rise and fall of pragmatism in the different journals. This model did not. James primarily ended up in the previous topic, Pierce was all over the place, but primarily in universals and particulars, and Dewey is here. There isn’t a single clear look at where pragmatism goes.

This topic also involves as much looking back at Dewey as it does original work. Of course in philosophy that’s sometimes a distinction without a difference; plenty of Kantians do exegetical work that is continuous with their work defending ethical conclusions. But still, it’s not great that the closest we get to a pragmatism topic is one that feels as much like a history of pragmatism topic as it does one that reflects pragmatism being done the “first time around”.

Relatedly, this model doesn’t give a clear test of the claims that Joel Katzav and Krist Vaesen make in their paper “On the Emergence of American Analytic Philosophy”. Here’s the abstract of their paper, which summarises it as well as I could do.

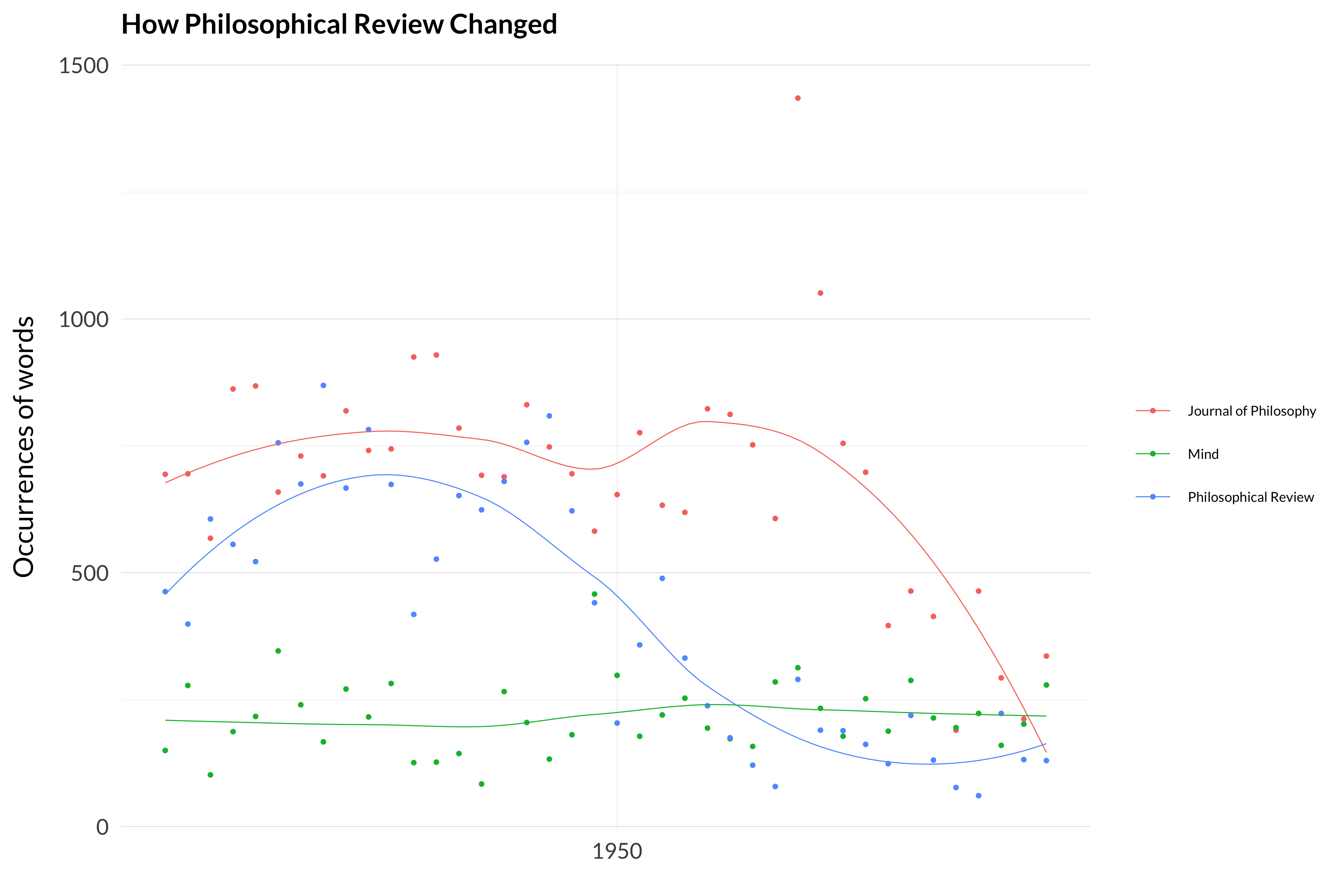

This paper is concerned with the reasons for the emergence and dominance of analytic philosophy in America. It closely examines the contents of, and changing editors at, The Philosophical Review, and provides a perspective on the contents of other leading philosophy journals. It suggests that analytic philosophy emerged prior to the 1950s in an environment characterized by a rich diversity of approaches to philosophy and that it came to dominate American philosophy at least in part due to its effective promotion by The Philosophical Review’s editors. Our picture of mid-twentieth-century American philosophy is different from existing ones, including those according to which the prominence of analytic philosophy in America was basically a matter of the natural affinity between American philosophy and analytic philosophy and those according to which the political climate at the time was hostile towards non-analytic approaches. Furthermore, our reconstruction suggests a new perspective on the nature of 1950s analytic philosophy. (Katsav and Vaesen 2017, 772)

The short version is that there was a change in management at the Philosophial Review in the late 1940s, and after that, what had been a flourishing diversity of approaches was narrowed down, and the Review only published papers that met with the approval of the analytically inclined editors. But the short version is a bit of a bad simplification of their view. For one thing, they note that one kind of pragmatism, the kind of scientific pragmatism associated with Dewey, continued well after the analytic takeover. Relatedly, a fall away in this topic isn’t seen at Philosophical Review until around 1948. For another thing, they note that through the early 1950s, some papers that were more representative of the old style of Review articles were getting through. This wasn’t the hard crackdown on some subjects that Gilbert Ryle executed at Mind. And for another thing, “analytic” is possibly not quite the right term for what takes over in the 1950s. Max Black is unambiguously an analytic philosopher, though a lot of the other folks who play signature roles, especially Norman Malcolm, have somewhat more difficult relationships to what would now be called analytic philosophy.

But the most relevant point is that if they’re right, there should be a topic that is a big part of Philosophical Review up until the late 1940s, then falls away very rapidly. And there should be, but in this model there isn’t. That’s not because Katsav and Vaesen are wrong though; it’s an idiosyncrasy of this particular model. It was very common when I was building different models to see topics that looked exactly like what would be expected if Katsav and Vaesen were correct. Rather than walking through a whole new model though, I’m going to look at some of the underlying data that supports their view.

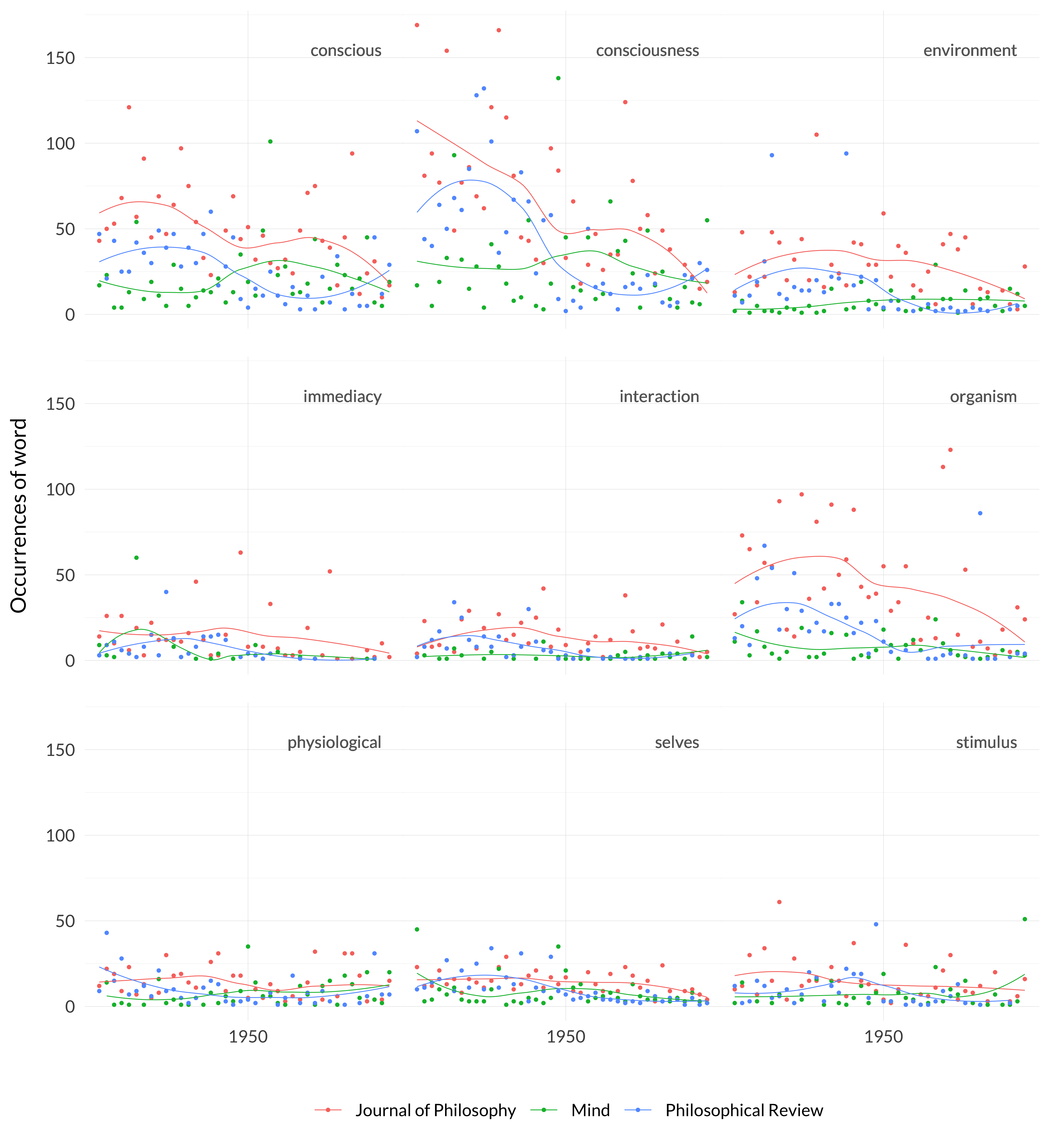

As a methodological note, I found the words that I’m about to focus on by building a small LDA model for just Mind, Philosophical Review, and the Journal of Philosophy for the midcentury years and looking for topics where Philosophical Review stopped publishing around the time Katsav and Vaesen focus on. And then I looked at the keywords for those topics. That’s to say, the words I’m about to talk about were not selected at random. But the data about them does, I think, show that something distinctive happened at the Review around the middle of the century.

What I’m going to do is show how often a bunch of words appeared in those three journals (i.e., Mind, Philosophical Review, and Journal of Philosophy), between 1930 and 1970. The words were chosen to give a sense of what kinds of things the Review published articles about before 1950 but didn’t publish about after 1950. This whole book has been based around using very fancy models to compute that kind of thing from the word frequencies. But sometimes it helps to just look at the word frequencies (or, in this case, the word counts) themselves.

I’ve put the words I’m looking at into three categories:

- Philosophy of Mind Words

- consciousness, physiological, conscious, stimulus, selves, interaction, environment, immediacy, organism

- Speculative Philosophy Words

- dialectical, contemporary, philosopher, synthesis, naturalism, metaphysics, idealism, categories, speculative

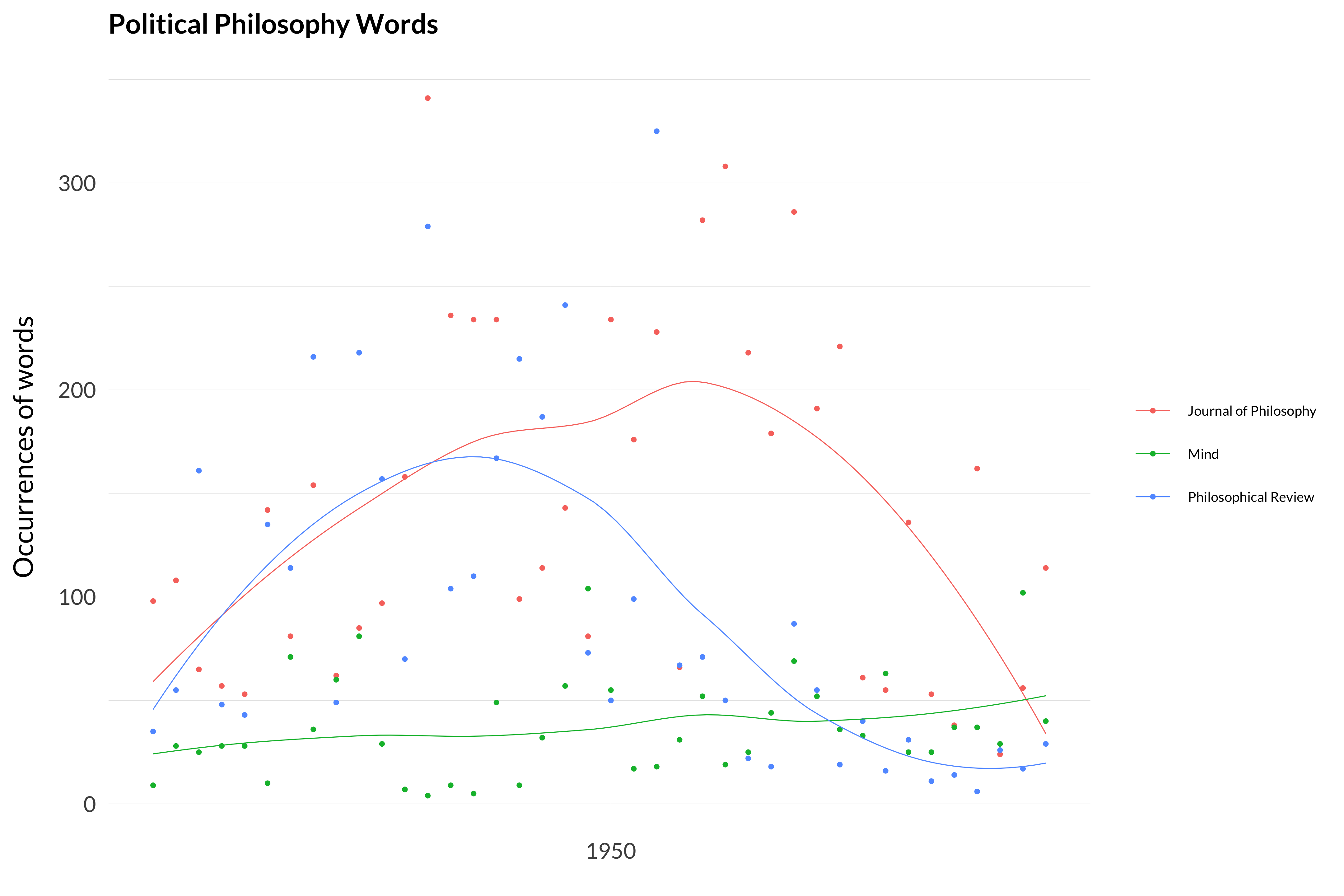

- Political Philosophy Words

- economic, society, national, culture, cultures, democracy

None of the three titles I’ve given here are exactly apt. (This is sort of the point; the work from before 1950 doesn’t even naturally fall into the categories that are now used.) Philosophy of mind includes a mix of empirical psychology and idealist-inflected reflections on the nature of consciousness. What I’ve called “speculative philosophy” is a bit of a grab-bag of things that the analytic philosophers didn’t like. And what I’ve called “political philosophy” is as much about social theory as politics as we’d now understand it. But as long as we keep track of what’s being measured, the terms provide a helpful enough shorthand.

I’ll start by looking at the philosophy of mind words. I’ll first graph out how frequently each of these nine words appears, and then look at what happens when they’re summed up.

Figure 2.14: Philosophy of mind words in the three big journals, 1930–1970.

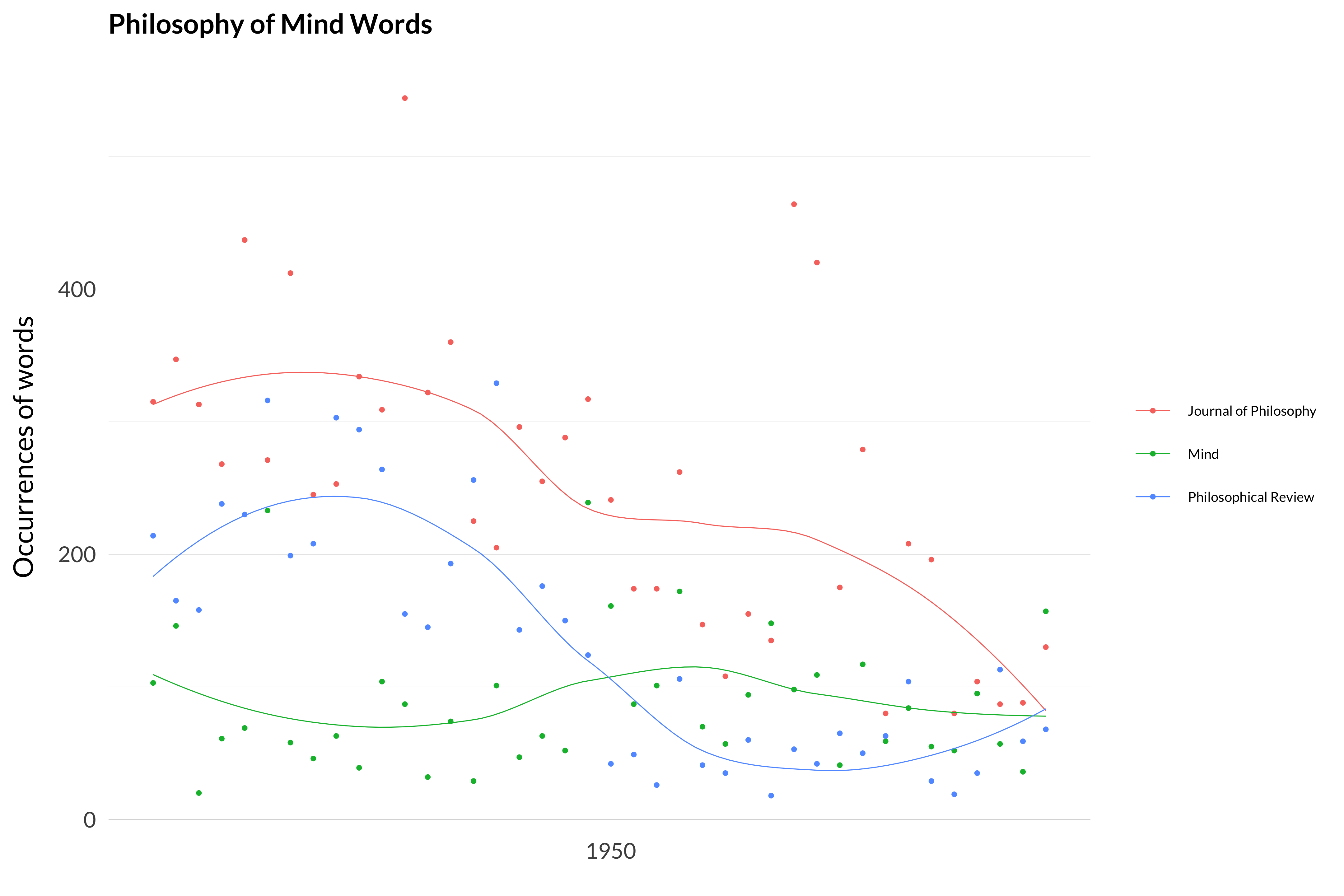

Figure 2.15: Sum of philosophy of mind words in the three big journals, 1930–1970.

There are three things happening here, which combine to form the distinctive graph at the end.

One is that Philosophical Review, like a lot of other philosophy journals, started out as a cross between what we’d now think of as a philosophy journal, and what we’d now think of as a psychology journal. Most such journals had split into one of the other by the 1930s, but the Review kept publishing psychology papers for quite a while. But they fade away over the period looked at here (i.e., 1930–1970).

A second is that as idealism drops out of the conversation, a particular kind of writing about consciousness goes away with it.

And a third is that behaviorism happens, and this really puts a damper on discussions of minds.

The third trend gets reversed eventually, but the second trend doesn’t. Post-behaviorist writing about consciousness on the whole does not feel a lot like prebehaviorist writing. (Though note that the model does think of “What Is It Like to Be a Bat” as a fairly old-fashioned paper.)

But the result of these three is a dramatic falling away in the late 1940s and early 1950s for these nine words.

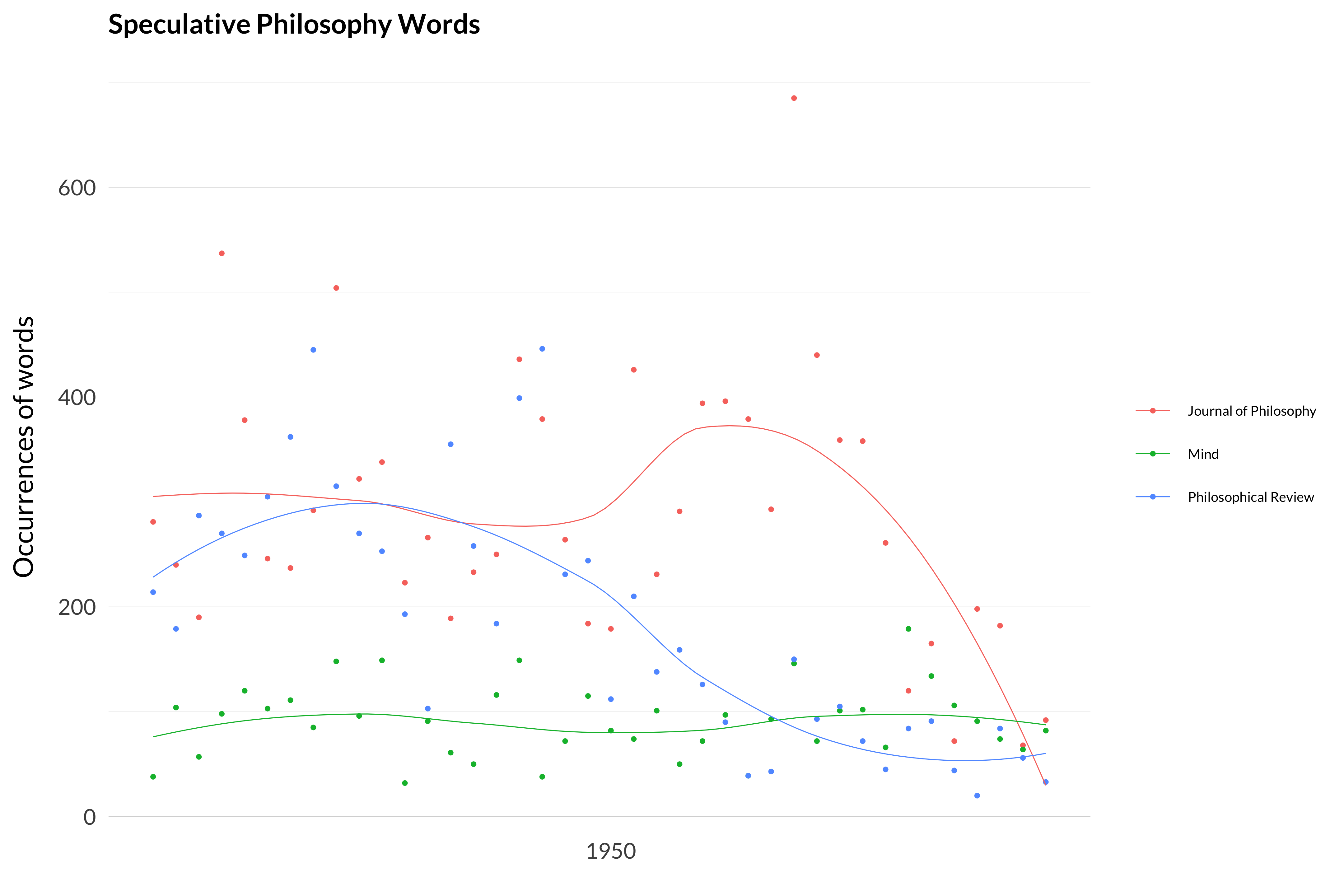

Now for what I’ve called speculative philosophy. I’m going to leave the Journal of Philosophy off the first set of graphs because some of the words were used so often in some of the years that it threw off the scale. I’ll come back to the Journal when I sum these graphs together. I’m also leaving off one data point for the Review: ‘philosopher’ which gets used 176 times in 1947. The loess curve that is shown does, however, take that hidden point into account.

Figure 2.16: Speculative philosophy words in (two of) the three big journals, 1930–1970.

Now I’ll show what that looks like after summing the nine words, and adding the Journal of Philosophy back into the picture.

Figure 2.17: Sum of speculative philosophy words in the three big journals, 1930–1970.

Again, there is a falling off after 1949, but it’s not completely sudden. Finally, I’ll look at the political philosophy words.

Figure 2.18: Political philosophy words in the three big journals, 1930–1970.

Figure 2.19: Sum of political philosophy words in the three big journals, 1930–1970.

Again, there is a fairly big drop, though here it seems like the break comes in 1952. And note from the word-by-word graph that it’s the parts that seem most like political philosophy in the current sense that hold up for the longest. Philosophical Review in the 1950s talked about democracy a bit, but it didn’t talk about culture.

I’ll sum all these together to get an overall picture. The next graph shows how often these twenty-four words appear in each of these journals in each year.

Figure 2.20: Sum of word usage for twenty-four distinctive words in the three big journals, 1930–1970.

By that measure, the 1950s at Philosophical Review do look quite different to the 1940s. This difference is why, I think, most models I looked at had at least one topic that disappeared from Philosophical Review right around 1950. For whatever reason this model didn’t have such a topic; this topic on Dewey is the closest, but I wanted to show why this was a common occurrence.

That said, the big change in Philosophical Review could be summarized by saying that it changed from being like the Journal of Philosophy to being like Mind. It wasn’t like they did something completely unprecedented, or were well out in front of the international trends.

And the changes that Philosophical Review made were eventually replicated at the Journal of Philosophy. Not just that, the changes preceded the glory years of the Journal in the 1970s. I don’t really think that the changes the Review made around 1950 were particularly bad things. But the evidence from word counts does point towards there really being a change.

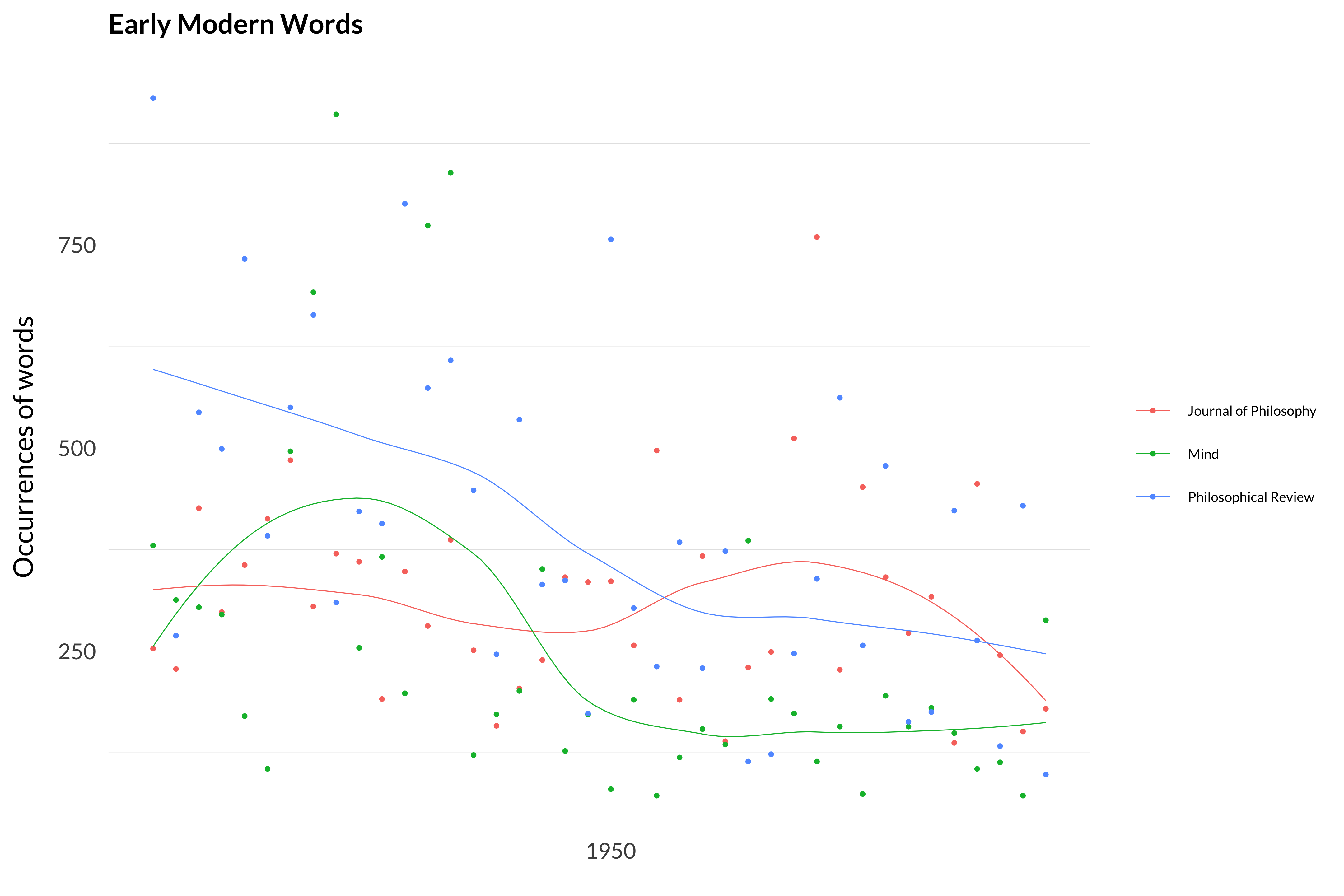

It’s not connected to Dewey, or the Philosophical Review, but I wanted to show how this kind of evidence from word counts can reveal a change in the journal. So I ran exactly the same kind of query as before, but with words connected to early modern philosophy.

- Early Modern Words

- idea, ideas, immanent, intellect, treatise, esse, hume, berkeley, spinoza, res, natura, descartes

Note the dramatic fall in the late 1940s, at the same time Ryle becomes editor of Mind. I will have more to say about this in what follows.

Figure 2.21: Early modern words in the three big journals, 1930–1970.

Figure 2.22: Sum of early modern words in the three big journals, 1930–1970.

Is it possible this kind of crude counting could detect a change in journal policy? I think that’s possible I think you have the answer right there. It’s a bit interesting that there is a fall at the Journal and the Review as well, but that’s a story for another topic.