4.5 Logic and Mathematics

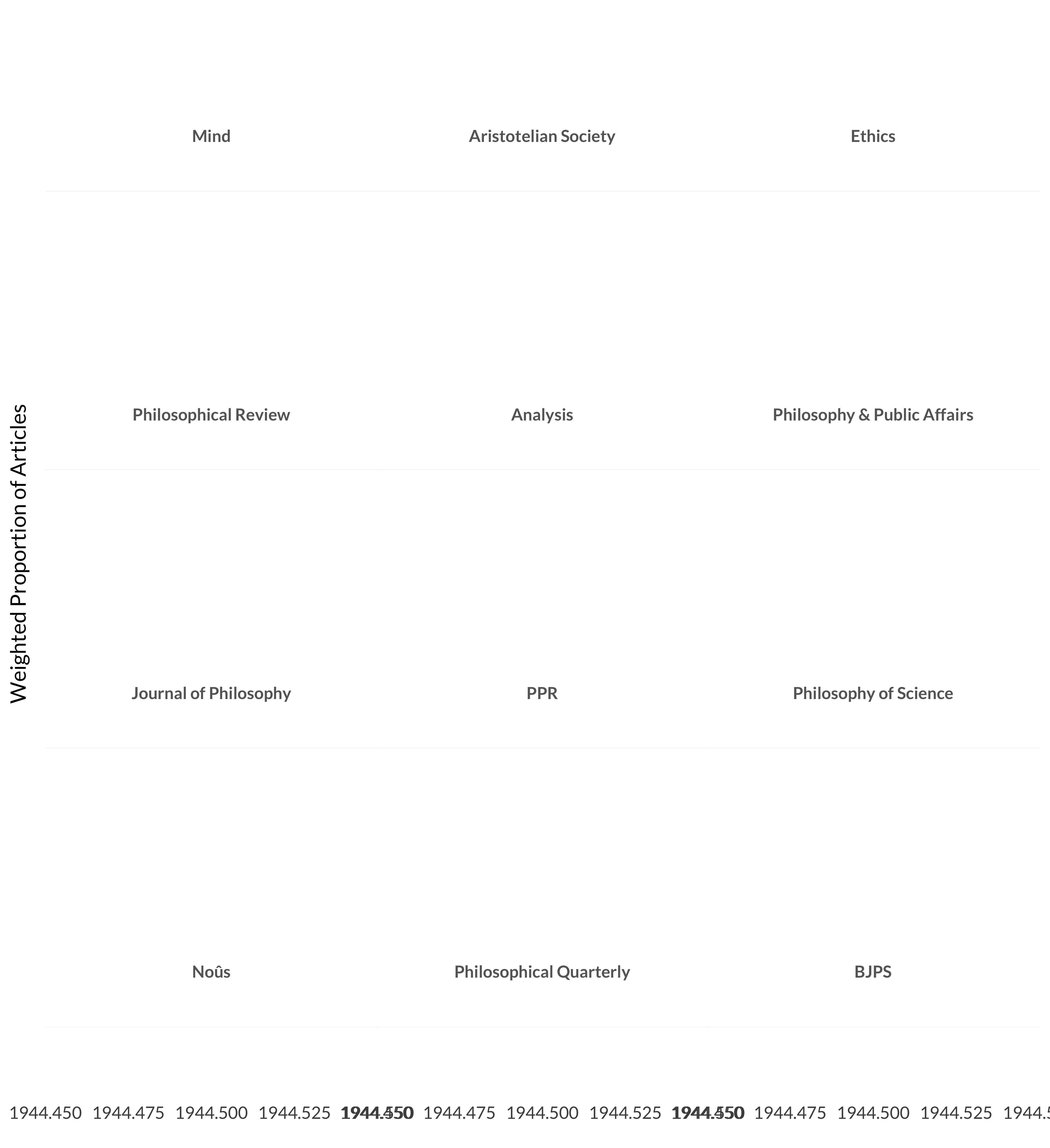

Figure 4.12: Proportion of each journal’s yearly publications in logic and mathematics.

The story of this category is a rise until midcentury and a fall afterwards. The journals start to give us a few clues as to what happened.

- Analysis starts off being very welcoming to logic and mathematics—so much so that it messes up the scales for these graphs a bit—but gets progressively less so over time.

- Noûs follows the same pattern.

- Mind under Hamlyn really stops doing any of this kind of work, though it returns in a hurry once Hamlyn leaves.

- Philosophy of Science moves strongly away from doing logic and mathematics work. And given the number of papers Philosophy of Science publishes in the 1990s and 2000s, this affects the numbers a lot.

So part of the story here, perhaps a large part, is a familiar refrain. The specialist journals are getting more specialist, and this is crowding out other things. But the downward trajectory in Analysis and Noûs matters too. Let’s look by topics.

Figure 4.13: Topics in Logic and Mathematics

That makes a bit clearer what happened. Two topics associated with positivism—definitions and verification—are in the category. And they peaked in midcentury and then fell.

They peaked at slightly different times, which I wouldn’t have expected. I guess a lot of the work in definitions is really trying to make positivism work, by getting a working account of definitions. And once verification itself becomes a topic, it’s because people are starting to think that the verification principle doesn’t have a defensible disambiguation. It’s not so much logic fell away, as that logical positivism did. And we knew that would happen.

It’s only up to 2 percent, but there is an interestingly steady rise in work on theories of truth. These play an important role in contemporary theories of logic, especially in motivating nonclassical theories. The optimistic take on this category is that the topics that have fallen are now basically at 0, so they can’t fall farther, while other topics are steadily rising. I’m not sure I buy that—I suspect we’ll see more falls if we extend this study beyond 2013—but it’s one reason for optimism.