"He taught me to look for the non-obvious ways to gain leverage times ten on an issue."[1]

McKinsey & Company Manager,

About Bill Drayton, founder of Ashoka

This page elaborates upon, and associates with sources, the hypothesized new value associated with establishing innovation's organizing principles -- broad access to a resource for high-leverage learning about innovation and its methods.

Part Four, the last section of this page, adds sample "how it could become" hypotheses. That is, how could this hypothesized value of access to high-leverage learning about innovation and its methods become available to students? The most fundamental "how" to address is that of developing a valid and articulate version of innovation's organizing principles, beyond a prototype.

"The curriculum of a subject should be determined by the most fundamental understanding of the underlying principles that give structure to the subject."[28]

-- Jerome Bruner, The Process of Education

Again, the feasibility of principles matters because of the hypothesized value associated with the potential public good of a developed, high-quality set of innovation's organizing principles.

The balance of text for this Part One discussion of the three accumulating levels of learning leverage, repeats the related text from the site's Home page:

Level 1: Leverage from Principles AloneWhen education psychologist and cognitive learning theorist, Jerome Bruner, established the conceptualization of "structures of the discipline" he argued that "the curriculum of a subject should be determined by the most fundamental understanding of the underlying principles that give structure to the subject."

Overall, structures would facilitate students' access to, and engagement with, a subject. Using Algebra as an example, Bruner held that understanding Algebra's underlying principles, or structures, allows students to recognize myriad problems as but "variations on a small set of themes."[29] For innovation, a framework of structures (or principles) would allow students to recognize its wide-ranging examples as "variations on a small set of themes." It might also facilitate recognizing new opportunities.

Bruner held too that a framework of structures of a discipline "permits many other things to be related to it meaningfully." [42] In the case of innovation's purpose and methods -- in effect, a modifier of the overall workplace -- there are indeed many things to which innovation relates. For example, a framework of structures or principles would:

- situate a treasure trove of innovation models and tools

- contextualize schooling's overall academic work

- reveal innovation's inclusiveness of varying types and levels of knowledge, varying human strengths, and more

- etc.

Overall, Bruner held that a framework of structures provides support for taking in "an enormous amount of information," akin to the cognitive science notion of "chunking."[30]

In a similar vein, Peter Drucker argued that it's a framework of "organizing principles" that permits "conversion of a skilled craft to a methodology or discipline" -- by making it "broadly teachable" -- as occurred in the past with engineering, the physician's differential diagnosis, and more (including the scientific method).[31] A framework of structures, or principles, provides not only for any individual learner's efficient access to the unifying concepts of innovation's driving purpose, forces, and methods, it allows too for the beneficial connection of shared understanding across learners.

Drucker made this argument within the context of describing the crucial need to convert innovation and entrepreneurship's skilled craft to methodology: He held into the early 21st century, up to his death, that a "post capitalist" society in which "knowledge is the only meaningful resource" means that: "Every organization … will have to learn how to innovate – and to learn that innovation can and should be organized as a systematic process." "What we need is an entrepreneurial society." [32]

Level 2: Leverage Points Associated with Innovation's Particular PrinciplesIn addition to the fundamental value of a framework, the particular content of innovation's organizing principles, at least according to the prototype principles, presents the additional value of three complementary and mutually-reinforcing learning leverage points, as follows:

- Intelligibility --

By speaking to innovation's driving constants, principles provide a lens for seeing innovation throughout the world and recognizing its overall purpose and methods as a particular category of creativity -- one that "integrates and applies" knowledge, to produce new value that catalyzes societal benefits. The lens allows not only for seeing every innovation example as but a variation on the driving constants, that perspective allows for seeing how much and in what ways innovation does vary, including highlighting primary types of variation (e.g., in the targeted societal-level change/s, in practitioners' medium of expression, pathways to hypotheses, types of knowledge, etc.). The lens also supports seeing brand new opportunities for the methodology's effects, and it facilitates understanding the way that innovation relates to other methodologies, the array of academic fields, etc..

Additionally, the prototype principles highlight potential for beginning instruction early (e.g., no later than middle school), akin to beginning early for methods of science: Whereas the label "innovation" is associated with large scale transformation, its forces (and associated methods) pertain to "all but that which might be called existential."[3] The methods pertain to change at any scale, including scale as small as a classroom and including potential for catalyzing meaningful change even at a young age.

- Engagement --

By highlighting innovation's essential creative structure of hypotheses, the principles support a familiar on-ramp for engagement. Hands-on practice can combine the hypothesis structure with other benefits of the organizing principles framework, such as the authenticity of small scale (e.g., community benefits as "societal" benefits), plus existing pedagogical structures (e.g., project-based learning) and innovation models and tools (e.g., design thinking, customer development, and many more). Feedback from active engagement, including learners' direct experiences of agency, collaboration, and more, is integral to gradually deepening understanding of innovation's core concepts.

In general, the principles' provision for grounding shines light on the potential for scaffolding engagement. For example, the forces do not require advanced knowledge; they only require pertinent knowledge. (For the domain of a school, this might include knowledge of the operations of recess, the cafeteria, recyling practices, bullying, etc., combined with knowledge about the school community.) Also, scaffolded engagement might begin with the "mental engagement" of considering examples, with sample practices (e.g., observation log), with generating and testing innovation hypotheses, and generally progressing one step at a time. As with science, students could return repeatedly to a framework of innovation's unifying concepts and driving forces and progress in hands-on practice with methods as they incorporate parallel growth in overall knowledge, skills, and interests.

- Embedded Personalized Guidance --

By highlighting the methodology's essential "force" of value to practitioners (the value of personally-compelling purpose), the principles reveal that innovation instruction both calls for and provides structure for students' exploration of personal sense of direction. For example, as Intelligibility supports taking in innovation's overall purpose and variation, and Engagement supports experience-based learning, the combination facilitates informed consciousness and development regarding questions such as: What types of change in the world do I think matter most? What types of value? How can I help create it? Hands-on innovation practice can help clarify leanings within innovation's methods and/or leanings that complement innovation's direct practice. Either way, learners have the benefit of knowing the overarching context established by the 21st century's need for innovation, including context for their schooling experiences.

In light of the rare quality of value of support for exploring/discovering a personal sense of direction, or purpose, Part Three of this Learning Leverage page elaborates this element of value, including sources.

The complementary and mutually reinforcing nature of these three learning leverage points includes dynamics such as: Intelligibility supports the dimension of personalized guidance, which supports engagement, which supports deepening intelligibility and personalized connection and engagement, and so on.With time and intentional structures, the combination of these dimensions can train the eye, develop discerning imagination associated with pertinent knowledge, cultivate innovation consciousness and its day-to-day impetus, cultivate personal purpose and signature strengths, and more.

Overall, a student is learning innovation's version of creativity, which includes understanding the present-day need for its expression:

- Within the 21st century, intelligibility of innovation's creative expression and its function of allowing for a sustainable world could be considered a type of literacy that is relevant to all.

- Beyond intelligibility -- developing personal innovation capability -- calls not only for a developing personal connection to types of purpose, it also calls for developing pertinent knowledge and skills, as discussed in sections below. The force of purpose can naturally motivate development of the knowledge and skills, much of which fits directly within the U.S. Common Core State Standards for grades K-12.

Level 3: Leverage from an Innovation Learning System

By allowing for broad access to innovation instruction that is grounded and connected across time and place, organizing principles provide for an innovation learning system, similar to the existing system for science. John W. Gardner provided an early voice for such a system. In a book about "the individual and the innovative society," Gardner framed innovation's instructional challenge in a way that remains pertinent over fifty years later:

"The classic question of [societal renewal] has been: How can we cure this or that specifiable ill? Now, another question: How can we design a system that will continuously reform (i.e., renew) itself, beginning with the present specifiable (ills) … (to the) ills (we) cannot foresee?" ... "Like a scientist in a lab, part of enduring tradition/system …"[35]

In the way that the scientific method has established an enduring tradition and broadly-accessible system for over a century of learning and practice, toward the purpose of advancing what is known about our world, innovation's organizing principles could establish such a tradition and system for the 21st century's urgently needed societal effects associated with innovation's function of resource leverage.

Leverage from an innovation learning system extends, or amplifies, Drucker's notion of converting a skilled craft to a discipline or methodology:

- First, since innovation's methodology is broadly pertinent as a modifier of the vast majority of disciplines and the vast majority of 21st century workforce roles, breadth of access is especially pertinent:

- Again, Drucker held that: "Every organization … will have to learn how to innovate – and to learn that innovation can and should be organized as a systematic process." "What we need is an entrepreneurial society." [32]

- For students within K-12 and into higher education, broad access would allow for trajectories of learning as students move from one teacher/grade/school to another. Again, akin to learning trajectories for the methods of science, a system allows for learning that is grounded and connected across time and place and also personalized.

- An innovation learning system also would provide for broad student access to the embedded structure of support for exploring and developing a personal sense of direction.

- What's more, innovation's methodology is fundamentally cross-functional and cross-disciplinary, making shared roots of understanding especially valuable.

Organizing principles would provide for, in effect, a "modular interface," or univeral language. [33]

Shared understanding of concepts and language would support individuals in nimbly "plugging into" innovation's instruction and practice across time and place.

From creativity researcher Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi: "What makes (the) breakdown in communication among disciplines so dangerous is that, as we have repeatedly seen, most creative achievements depend on making connections among disparate domains." [34]

- Indeed, it seems only a matter of time until the majority of a university's departments, or disciplines, will include "Innovation Methods" curricula in parallel to ~universal "Research Methods" curricula, including the parallel of beginning with organizing principles.

This section looks at the special value of each of the three learning leverage points associated with this site's prototype version of innovation's particular organizing principles:

Complementary and mutually reinforcing, these leverage points are hypothesized to offer students the value of:

- Intelligibility

- Engagement

- Embedded personalized guidance

- support for successfully thinking about and acting on innovation's essential purpose and forces

- support for progress in personal sense of direction, or purpose.

Tactically, the levers can be complemented by existing pedagogical structures (e.g., project-based learning, e-learning) and existing innovation models & tools (e.g, design thinking).

Also, a separate page of this web site features sketches of sample Learning Applications, motivated by the principles and complementary learning levers, to address a sampling of new opportunities for programming and tools.

A. Lever of Intelligibility

"To do things differently, we must learn to see things differently. Seeing differently means learning to question the conceptual lenses through which we view and frame the world ... To see differently, we need new intellectual constructs."[36]

John Seely-Brown, 1997

A Lens --

A high-quality version of innovation's organizing principles provides a lens for seeing innovation's driving fundamentals:

Well-articulated principles provide a conceptual on-ramp.

Students can view concrete innovation examples through the lens, seeing the fundamentals that drive each example, from the simplest to the most complex. Fundamentals such as:

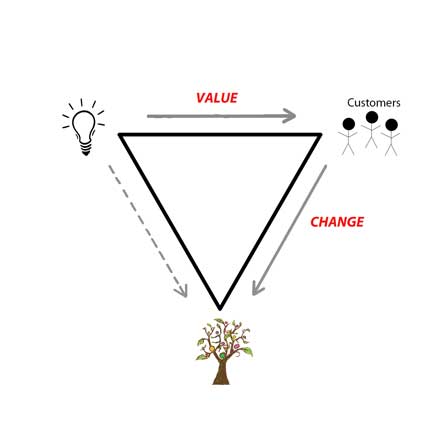

- the creative structure of hypotheses (about new value)

- value as force for change

- resource leverage and its ultimate purpose of collective benefit

By recognizing widely varying examples of innovation offerings as but variations on a small set of driving constants:

- The lens also supports seeing how much innovation's examples do vary around the constants, with examples reaching into many different societal domains and calling for the input of widely-varying knowledge, talents, and interests.

- Indeed, small-scale examples of the forces (e.g., contexts as small as a classroom) convey that even young students can begin to harness the forces toward real and personally-meaningful results.

In this same vein, the lens captures what cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham calls the "unifying concepts that come up again and again" -- "a limited number of ideas carried through a curriculum for years as different topics are taken up."[37] It provides support for successful thinking to which students may return time and again, for deepening learning.

Plus, like Bruner, Willingham points to connecting the concrete with the abstract as the best way for students to gain traction with understanding the unifying concepts: "The surest way to help students understand an abstraction is to expose them to many different versions of the abstraction," where the connection is explicit. [38] Examples in the form of stories add the general learning lever of "meaning" for even greater effect of connecting the concrete with the abstract:

"The human mind seems exquisitely tuned to understand and remember stories. Stories are believed to be treated differently in memory."[39]

Overall, unifying concepts and plentiful concrete examples support students' successful thinking regarding innovation's intelligibility:

"What is innovation? How does it work? Why does it work? Why does it matter?"

Taking in Enormous Amount of Information --

Bruner pointed also to a subject's framework of underlying principles as support for taking in "an enormous amount of information." [40] Cognitive science uses the term "chunking" for this benefit to cognitive processing and memory. [41]

This benefit is very much pertinent to learning about innovation, given how broad reaching and varying it is. The framework established by innovation's organizing principles serves to situate what is indeed an enormous amount of information, which can be introduced and assimilated over time. For example:

- recognizing standard types of variation (e.g., aiming for effects of "planet" vs. "people" vs. "profit")

- appreciating similarities and distinctions of innovation's two types of hypotheses ("what could be as new compelling value" and "how it might become an offering and catalyst of change")

- recognizing the way that innovation's array of models and tools support different aspects of the methodology and/or different types of oferings

- with time, considering the fit of an array of existing and emerging constructs such as: knowledge management; intellectual capital; user experience; data science; high tech anthropology; etc.

- and much more.

Permits many other things to be related meaningfully --

Bruner argued too that understanding a subject's underlying principles, or structures, "permits many other things to be related to it meaningfully."[42]This too is highly pertinent to learning about innovation. For example:

- Relating both the purpose and methods of science and invention/technology to innovation's purpose and methods, including:

- the way that the three methodologies share the essential creative structure of hypotheses

- and the way that the testing of innovation hypotheses (e.g., for the purpose of assessment / decision making) overlaps somewhat with the testing of hypotheses within the other methodologies

- Relating schooling's structure of academic disciplines to the economy and society's structure of producing value.

- Understanding "creativity" as broader than "the arts" (or even perhaps different from), including understanding the "paradigmatic creativity" associated with hypotheses versus "narrative imagination" associated with "gripping drama," etc.

- Relating the whole of knowledge (including information, big data, ordinary knowledge, and personal "secrets") to innovation's process of "integrating and applying" knowledge, with particular strands of knowledge as typically pertinent.

- Mapping higher education's fields of knowledge to innovation's two types of hypotheses (e.g., hypotheses for "what could be as new value" often draw on deep knowledge of a particular field, spanning virtually every university field from Agricultural Science to Kinesiology; "how" hypotheses, in contrast, often draw on functional skills such as information technology, engineering, marketing and communications, and many more).

- Considering the proposition that innovation represents the knowledge base of entrepreneurship, as argued by Peter Drucker.[43]

Overall, within a trajectory of learning, innovation's unifying concepts can be continually related to the "close neighbor" concepts of science and invention, per the type of summary in the following table:

Support for Personal Connection (Seeds of Inspiration) --

By revealing innovation's broad expression and demystifying how its forces allow for positive change -- including, as Steven Johnson noted, "Good ideas are not conjured out of thin air; they are built out of a collection of existing parts" [43-5] -- intelligibility can serve as a leverage point regarding how one might participate. This can begin early, in small but meaningful ways.As Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and colleagues have noted:

"Humans can observe and/or be shown how activities of humans have changed the environment, fostering realization that other people may be able to also bring about change ... A sense of what has been done helps lead to a sense of what might be done as well as an appreciation for the kinds of established constraints that might affect imagined changes." [44]

Even without hands-on engagement, assignments could, for example, call for selecting one's favorite innovation example(s), reflecting on why they're favorites, and noting the types of knowledge ("existing parts") connected to form these pictures of possibility.

See a fuller discussion of support for personal connection under the third learning lever heading of "Embedded Personal Guidance."

Trajectory of Intelligibility --

Overall, the lens of innovation's organizing principles (along with hands-on practice) can launch and support a trajectory of deepening intelligibility, supporting both deepening inspiration and more effective engagement.For example, the Kauffman Foundation's Panel on Entrepreneurship Curriculum in Higher Education described the benefit of maturing intelligibility in distinguishing examples of excellence, drawing on an analogy with music:

Departments of music composition cannot make students creative. But studying how great music is made can ignite whatever creativity students possess and help bring it to expression. The aim of studying composition is to unpack works of genius and excellence and thereby lead students beyond imitation to originality. … Making innovation intelligible may help students to imagine and engage in entrepreneurial activities they otherwise might not have considered. [45]

Innovation's organizing principles can support continual "unpacking" of excellent examples, or what Willingham refers to as "understanding the parts and the whole." [46]Deepening knowledge of innovation's unifying concepts supports successful thinking for unpacking such as:

- the nature of "forcefully positive value"

- the existing knowledge that was connected to form each hypothesis within the overall set of : "what could be" as new value and "how it could become an offering accessible to customers and a catalyst of change"

- practitioners' pathways to the hypotheses

- the nature of practitioners' personal connections to a purpose addressed by the hypotheses

- organizational context

- the nature of adoption needed for societal effect (transactions alone vs. customer change in behavior and/or capability)

- types of, and extent of, societal effect (profit, planet, people)

- similarlities to other offerings (e.g., the "Uber" of airplanes).

Plus, examples of unpacking a bit more:

- The practitioner's original point(s) of reference. For example:

- starting with a goal (a type of change, general or particular)

- starting with new technical capability or new knowledge

- starting with observation of customers, marketplace, industry, etc.

- Role of technology and its centrality to the offering (e.g., new technology versus "appropriate" technology versus new application of existing technology versus no central technology role).

- The levels, types, and strands of knowledge connected.

- Classification of leverage and scale (e.g., "disruptive," transformational, other), which could begin with an established classification system (e.g., by Jeff DeGraff and Shawn Quinn).

At this site's Applications page, three of the tools feature examples and stories that are structured by the intelligibility lever's lens:

- An online gallery of innovation profiles is sketched as a new type of learning tool, where each profile is structured according to a template that is based on innovation's organizing principles. The gallery idea, as sketched, is both searchable (by tags representing myriad types of variation) and interactive. The sketch also points to a simple prototype of this type of tool at www.InnovationAgents.org.

- Cases of social innovation viewed through the lens of the prototype principles are intended to help convey the type of unpacking that a framework of principles can support.

- "Elegant video lectures" are to convey a developed version of principles/concepts, potentially within a venue such as the Khan Academy (or other open educational resource). A potential model for such lectures might be a principles-structured curriculum about the subject of engineering, designed for new engineering students.[46-5]

B. Lever of Engagement

"No amount of doubling down on math and science courses is going to produce the innovators we need in the 21st century. ... The key is engagement." [47]

Richard Miller

President, Olin College of Engineering

Channel of "Good & Good for You" --

The light that the prototype organizing principles shines on innovation's essential purpose and forces, in turn, shines light on opportunities for scaffolding students' hands-on engagement with the purpose and forces.In particular, the combination of the three learning levers associated with the principles supports an on-ramp for engagement, which can launch a trajectory of learning that can be understood only by virtue of experience.

It's learning that is both "good" and "good for you":

- "Good" in terms of the positive aspects of direct experiences of innovation's version of creativity, such as:

- "What is needed is an opportunity for youth to experience the joys and responsibilities of making things happen" ... including attention to "activities that are halfway between the spontaneous play of childhood and the serious work of adulthood."[49]

- "Effective surprise" -- "Good observations often seem simple in retrospect, but the truth is that it takes a certain discipline to step back from your routine and look at things with a fresh eye."[50] As Wendy Kopp put it regarding a national teacher corps, "How could this not already be in place?" [51]

- "A certain unclassifiable sixth sense of what is possible" -- following experience with a new idea that catalyzes change. [52]

- "The creative process is ... one of the most powerful and intimate involvements with life."[48]

- "Creative confidence" as described by IDEO's David Kelley and Tom Kelley. [53]

- Even "brushes with purpose." [54]

- "Good for you" in terms of deepening learning, including:

- Willingham argues that deep learning is above all a product of practice, especially hands-on practice. [55] Practice cultivates understanding of a subject's parts and whole, and it relates the challenging abstract concepts to the concrete.

- For innovation, learning based on firsthand experience allows for a different perspective on unifying concepts. As one big example, firsthand experiences can teach that seemingly simple concepts (principles) are not so simple to adhere to, including for longtime practitioners. [56]

In particular, practice can include the experience of finding oneself strongly attached to an idea ("inner-driven") in which there is not customer interest (not "other-focused"). This potential experience supports not forgetting the "simple" principle that customers are innovation's gatekeepers. Practice supports learning to navigate the combination of inner-driven and other-focused.

- Acting on hypotheses can be eye-opening in general including: perspective regarding the level of logistics involved even for small-scale efforts; discovering personal strengths and noticing others' strengths; and much more.

- Practice can support customer-focused experiences of applying technology or advances in science/invention toward innovation's purpose of resource leverage. As Steve Jobs put it: ~"We're the ones who are stupid if customers can't figure out how to operate the devices we make."

- In general, engagement calls for students to practice wide-ranging skills, including those associated with the Common Core State Standards, which can help cultivate those skills for overall academic and life purposes.

The engagement scaffolding opportunity borrows from Csikszentmihalyi's example of a "flow" channel, where each of a series of experiences is neither too difficult nor too easy. If the experience is too difficult, it provokes anxiety, or perhaps disinterest and lost opportunity in the case of innovation's methods. If it's too easy, it's boring. [57]

Willingham reinforces the notion of this "just right" channel: "Working on problems that are of the right level of difficulty is rewarding, but working on problems that are too easy or too difficult is unpleasant." [58]

Most important ultimately, Csikszentmihalyi holds that every experience within the flow channel produces growth in abilities, for a potential channel of ever-developing growth and personal evolution. [59]

Hands-on practice with innovation's constants lends itself to the structure of a flow channel, based on fine gradations of difficulty combined with vast possibilities for personalization. Again, Drucker noted that innovation's function and forces "pertain to all activities of human beings other than those one might term 'existential' rather than 'social.'" [60]

- The amount of leverage realized for any given student-generated innovation hypothesis (or set of hypotheses) may not be of the size or scale to be labeled "innovation," but the experience of generating and/or acting upon a hypothesis about forcefully positive new value would rightly be labeled engagement with innovation's purpose and forces.

- And while the objective here is not to generate flow per se (which focuses on engaging/developing an individual's signature strengths), the objective is to take advantage of innovation's gradations in order to support students in realizing the practitioner's positive experiences and to promote interest in continued engagement. With creativity there can be power in even quite small experiences.

This overall approach is similar to existing experiences with the methods of science, and consistent with science, hypotheses represent the essential creative structure.

Hypotheses as Fundamental Structure of Engagement -- Most fundamental to engagement is working with innovation's essential creative structure of hypotheses, featuring the principles-based methodological constants of:

- Generating and testing hypotheses (both "what could be as new value" and "how it could become")

- Situating "what" and "how" hypotheses within a design for action (e.g., using a tool such as the Business Model Canvas)

- Acting on a hypotheses-based design for action and assessing the action/results.

Throughout engagement, organizing principles provide constant reference and benchmarks for innovation's hypotheses, emphasizing the same fundamental purpose and forces, for the smallest application to the largest.As one of those forces, all experiences should emphasize what each student finds important, compelling, interesting, etc., even within "small" examples:

It's difficult to convince someone to care deeply about advancing a transaction-based subject that they do not already care about. But if the practitioner's intrinsic interest is in place, it allows for the methodology's force of "inner-driven and other-focused."

IDEO's General Manager, Tom Kelley, advised:

"(T)his work [of understanding customers] requires curiosity. How can you get better at it? Find a field that commands your interest." [61]

To help foster personal connections, hands-on practice can and should incorporate regular variations of the methodological constants -- guided by common categories of variation described under Intelligibility (e.g., societal benefit in terms of profit, planet, and/or people; nature of value offered; hypotheses for "what could be" vs. "how it could become"; and so on). The variations highlight innovation's broad and yet structured space for personal preferences. It would make sense for students to keep a log, or journal, of variations explored and associated reflections.

Hypothesis Testing:Actively generating and testing innovation's hypotheses reinforces and deepens learning, including understanding fundamental differences versus hypotheses for the purpose of science. (Conceivably, the differentiation could support skill with hypotheses for science too.)

The purpose-based departure includes actively considering the different basis for testing innovation's hypotheses and implications for designing those tests:

Even as the activity of testing represents an area of overlap between methods of innovation and of science, testing for innovation's purpose of resource leverage is fundamentally different from testing for the purpose of science (advancing knowledge).

- For science, "truth" is with respect to a formal, existing reality.

- For innovation, "truth" is with respect to customer response to possible new value (and associated possible resource leverage).

Tests of innovation's "what" and "how" hypotheses typically involve gauging customer response, which informs decisions about action (e.g., whether or not to act; what to expect from action). There may be a series of potential actions and decisions, such as:

- whether or not to pursue an idea at all (where an offering may be represented initially as a description only, or what the Lean Startup calls a "minimum viable product")

- preparing to act on the idea, which may include testing and adjusting elements of a design for action and which is likely to involve arranging for resources and other aspects of implementation planning

- assessing, or evaluating, implementation (which may inform decisionmaking about future action, including broadening the scale of action).

At each stage, the rigor of testing innovation hypotheses, determined by the practitioner, reflects the extent of resources at stake (including resources limited to students' time, energy, etc.). Also, at each stage, the design of testing may include both "test" and "control," drawing on fundamental research and/or analytic methods.

Sample Scaffolding -

The following set of stages provides an example of the opportunity to scaffold hands-on practice with innovation's methodological structure of hypotheses:

- Build on prior experiences (using intuition & mental engagement)

- Explore practices of the methodology (e.g., observation, questioning, testing)

- Draw on engagement tools (e.g, providing for boundaries to action, the option of innovation "recipes," and more)

- Aim toward elements of mature creativity

Each of these sample scaffolding stages is described in brief:

- Build on Prior Experiences

The omnipresence of innovation's forces means that engagement allows for beginning with intuition, especially within "mental engagement."

- Virtually all students have hands-on practice as customers responding to offerings of value (especially as defined by Drucker -- referring to all but that which is existential rather than social).

- In this sense, it's likely that most have experience too of offering value to others.

That base of experience gives them an intuitive understanding, which can provide support for a successful start of mental engagement as an innovation agent. To launch initial student engagement, connection to the organizing principles can be loose and then brought to bear as a structured reality check of sorts -- a basis for cognitive processing that follows engagement.

For example, drawing on a known subject like environmental sustainability (and one that is deemed important widely among today's youth), questions like those in the box below can be engaged and then related back to the organizing principles.

- As a side note, there is no reason for every teacher to need to come up with topics and questions. Instructional resources could be generated, featuring a variety of topics to support this type of mental engagement. (The sample application for the separate discipline of engineering, noted at the end of the Intelligibility section, just above, provides an example of concepts linked to exercises. It's a curriculum-based book: Principles of Engineering.)

- Topics could be tailored to learner age, with respect to the starting point of life experiences. However, for all beginners, regardless of age, the gist of the questions probably would be similar, focusing on the principles' driving constants and with relatively straightforward scenarios.

- For example:

Mental Engagement --

- How much of what you could recycle [readily] do you recycle (or compost, etc.)? When you don't recycle, what's the reason?

- Is "value" associated with your amount of recycling -- value such as "ease" and/or "meaning" (connection to a purpose larger than oneself).

- What might lead you to recycle more? (Or less?)

- What might you do if you wanted to increase others' recycling/composting in a given context (home, classroom, cafeteria, school, restaurants, etc.)?

- Consider intuition-based answers as working hypotheses. Probe for what knowledge students are drawing upon.

- Ask how they might test their ideas and/or how they might investigate what types of value would most influence the "customers" in that context -- the gatekeepers.

- Proceed with "how" hypotheses.

- The array of "how" hypotheses that arise intuitively might then be written into a large "business model canvas."

- Students could work in groups on this or on different types of examples, guided by their interest, and the class could consider overall examples.

- With all hypotheses generated from intuition, unpack them. Ask students to consider what knowledge they drew upon for their hypotheses. What's the category/strand of that knowledge? What is not known that matters?

- With class sharing, make constant reference to the organizing principles. Also, call upon pedagogical structures such as those from Writers' Workshop (.e.g, beginning with "I like [this element of the example]" and proceeding with "I'd like to see more value in ..." etc.]).

- If motivation is there, proceed with experimenting/implementing.

- After this exercise in mental engagement (or one that begins with mental engagement), refer to the real-world example of the one-time new offering of curbside recycling pick-up. (Ready access to this and other such stories could be developed.)

- Ask if there are ways other than the force of value to generate the same extent of recycling and its collective societal benefit. Consider the comparative resources needed for different approaches.

- Explore innovator practices (e.g., observation, questioning, testing) -

Cultivate regular practices that have been associated with fertile creativity, such as purposeful observing, questioning, and experimenting/testing -- looking outward through the principles-based innovation lens. With this, cultivate practitioners' internal and external conditions of creativity, such as: openness, flexibility, and complexity. [62]

For example, for the sample practice of logging observations, begin perhaps by sharing with students the findings of author Steven Johnson, who investigated shared types of practice among an array of creators (including Charles Darwin) across the domains of science, invention, and innovation, over centuries, where one practice was keeping a log of observations. [63]

Practice of Logging Observations --

There could be "questions for the week," tailored perhaps to particular innovation concepts.

For example, honing in on the concept of resource leverage, a question for the week might be:

- Where do I see resources underutilized? Or phrased differently, where is there waste? (For example, many school buildings are empty all summer and on weekends, youth have strengths that a community could benefit from, a lot of edible food is thrown away, outgrown youth sports equipment, wasted electricity, etc.).

- In advance of logging, discuss actual innovation examples that have focused on the innovator practice (observation) that highlights the question for the week. For underutilized resources, the overall "sharing" economy offers a cluster of examples (e.g., ZipCar, Uber, AirBnb). Similarly, Salman Khan, in founding the Khan Academy referred to the "ridiculously underutilized resource of the Internet" for benefits to education. Make examples vary enough to keep students' minds open.

- Generally, guide students to actively consider resources of all types, including knowledge/information resources.

- After the period of observation, have students reflect independently on what they logged, including reflecting on how the underutilized resources might be used to offer new value to some set of "customers." That is, how can the resources be made more fruitful?

- Also share observations. Perhaps the instructor could cluster students' observations into categories for positing on poster paper. The clusters and particular examples then could be discussed, built upon, and potentially even serve as a basis for implementation.

The same practice of logging observations could be applied to other concepts. For example, "value as a force for change" could be associated with an observation question of the week such as:

- Where are people experiencing "rough edges" in their activities? For example: hard to get a phone signal, hard for youth to find a babysitting job and/or for adults to find babysitters, experiences of being new to a school, experiences of being bullied, some kids want to play sports and don't have the resources for equipment.

- Or similarly, where do I notice opportunity for improvement (e.g., school lunches? raise funds with better offering than selling popcorn or pizza dough?)

Structured exercises for different practices could help students develop day-to-day consciousness of innovation's purpose and opportunities. Not only are examples bringing concepts to life, the examples are personally generated. Continued engagement can support "deep memory" of the essential purpose and forces, all toward support for "opportunity finding." Experiences with a variety of practices also could lead to student adoption of preferred practices (an element of personal connection).

Hypothesis testing provides additional focal opportunity for engaging a fundamental innovation practice/method. Testing includes the benefit of being bounded and yet essential to the practice.

- Conceptually, hypothesis testing provides an opportunity to consider the purpose-based difference between hypotheses for innovation vs. for science and invention, but also to consider an area of overlap that varies across innovation examples. That is, since the reason for testing is different, the design for testing often is different throughout innovation's practice. For innovation, test design considers the resources that are at stake if customer interest is low, considers the resources needed if interest is high, etc. In general, test design asks: How accurate does the gauge need to be and for what reason?

- Testing innovation hypotheses can begin informally, in keeping with the power of small. Students could be assigned to test hypotheses where customers are peers, siblings, neighbors, teachers, coaches, community members, etc.., in person and/or online. Testing can help them consider who represents their customer segments and much more. For example:

- In-person testing could exercise students' empathy muscles. It could also help stretch their "inner conditions" of openness, flexibility, and comfort with complexity.

- Testing also could involve hands-on experience with the practice of prototyping, especially with "minimum viable products" -- as minimal as drawing a picture of an envisioned offering.

- Finally, depending on student interest, testing could lead to revising hypotheses (and/or testing revisions).

- Draw on Innovation Models & Tools

The message within a cookbook's introduction from Julia Child and colleagues speaks to the highly valuable support that "recipes" can provide for early hands-on practice with "fundamental techniques":

"Our primary purpose in this book is to teach you how to cook, so that you will understand fundamental techniques and gradually be able to divorce yourself from a dependence on recipes." [64]

Since innovation's organizing principles situate an array of models and tools, continued reference to the principles can support experimenting with different tools and also support recognizing how various tools provide differing aspects of support.

Within instruction, tools can be selected based on varying tasks (e.g., from hypothesis generation to testing, implementing, and assessing):

- Some models and tools emphasize an overall process, along the lines of a recipe for cooking (e.g., "design thinking" and "lean startup"). Others support one or more particular aspects of the work (e.g., a model of ten innovator "personas" describes varying ways to connect personally to innovation's purpose and practice). In some cases, it is skilled cooks, not beginners, who can make the best use of a recipe (e.g., the benchmarks of "disruption"). [65]

- For learners, the combination of a principles framework and models/tools is complementary and potentially synergistic. For example: the intelligibility offered by principles allows for an overall purpose; tools can support learners in getting started; and the framework of principles provides benchmarks (e.g., considering all pertinent strands of knowledge for innovation hypotheses, confirmation of forcefully positive value to customers, etc.).

- See a mapping of an array of differentiated innovation models and tools to the prototype principles, plus brief descriptions.

Eventually, actively situating tools vis-a-vis the principles and overall methodology can support students in learning to use innovation tools nimbly.

Along with tools designed specifically to support innovation's methods, the established pedagogical structures of tools such as project-based learning (PBL) represent a seemingly strong complement for hands-on practice with innovation's methods. For example, PBL's established guidelines for boundaries supports acting on hypotheses that students find compelling or simply worth trying out.

Action can cultivate:

- Practical abilities -- especially for those who have undiscovered talents in this important practitioner skill area -- while containing the demands of implementation within learning contexts. [66]

- Innovation's version of participating in teams -- ideally "collectives of purpose" -- where the dynamic is both cross-functional (a division of labor) and collaborative (a merging of minds). [67]

- Learning from failing -- especially if learners recognize ways they didn't observe fundamentals and especially if the failure motivates them to adjust and try again.

- Concrete perspective for relating innovation's methodology to science, invention, and more -- in support of reflection about personal preferences among these complementary methodologies, including over time, or perhaps about ways to integrate them (e.g., focusing on using innovation's methods to leverage advances in knowledge or technology).

- And much more.

Aim Toward Maturing Creativity -

Descriptions of mature creative capability reinforce the value of a means to scaffolding. They reinforce the pertinence of intentional and structured cultivation over time.

To begin, consider in the box just below the developmental demands indicated by Robert Sternberg's WICS model (Wisdom, Intelligence, and Creativity Synthesized), which unpacks fundamental elements of mature creativity for the explicit purpose of understanding what is to be learned. [68]

Note that the WICS model addresses creativity in general, which encompasses science and invention/technology, but seems different from "art."

"Wisdom, Intelligence, Creativity Synthesized" (WICS) --

Building on a period of funded creativity scholarship from the latter half of the 20th century, Sternberg drew on the work of multiple scholars in elaborating this model: "Wisdom, Intelligence, Creativity Synthesized (WICS)." He presents the elements in reverse order of the WICS acronym:

- "Creativity": "(W)ork that is novel (original, unexpected), high in quality, and appropriate (useful, meets task constraints)."

"Creavity is the potential to produce and implement ideas that are novel and high in quality. (Creativity) goes beyond the creative intelligence ... in that it contains attitudinal, motivational, personality, and environmental components as well as the cognitive one of creative intelligence."

- Intelligence: "Creative work and the broad-based creativity underlying it, requires applying and balancing the three intellectual abilities -- creative, analytical, and practical -- all of which can be developed."

"Creative ability is used to generate ideas. ... Without well-developed analytical ability, the creative thinker is as likely to pursue bad ideas as to pursue good ones ... Practical ability is used to translate theory into practice and abstract ideas into practical accomplishments. It is also used to convince other people that an idea is valuable ... (and) to recognize ideas that have a potential audience."

- "Analytical ability involves analyzing, evaluating, judging, inferring, critiquing, and comparing and contrasting."

- "Creative ability involves creating, designing, inventing, imagining, supposing, and exploring."

- "Practical ability involves applying, using, implementing, contextualizing, and putting into practice."

- Wisdom: "People can be intelligent and even creative but also foolish."

"(W)isdom is the application of intelligence, creativity, and knowledge as mediated by positive ethical values toward the achievement of a common good through a balance among (a) intrapersonal, (b) interpersonal, and (c) extrapersonal interests over the short and long term."

WICS & Common Core --

The WICS model of creative capability (again, encompassing multiple types of creativity, including science) highlights the importance of proficiency with the K-12 Common Core Standards (CCSS) as one fundamental element.

However, considering the model's multiple elements of ability, the CCSS seems mainly to serve the analytical ability within "Intelligence," with modest attention to cultivating the model's other types of skill.

Structured innovation learning experiences could support broader development of the WICS ~checklist of what is needed for maturing creative capability. Plus, if students are engaged in learning about innovation, those experiences actually can support development of the areas of overlap with the CCSS in addition to broadening development.

For example, scaffolded experiences could support the WICS "Creativity" element -- attitudinal, motivational, personality, and environmental components (beyond creative thinking) -- and much broader development of the "practical intellectual abilities" and "Wisdom" element. (Nobel prize recipient Daniel Kahneman emphasizes the need to cultivate "responsible creativity.") [71])

Similarly, other resources highlight the function of engaged experiences with the humanities, again for all types of creativity:

"For, in effect, the humanities have as their implicit agenda the cultivation of hypotheses, the art of hypothesis generating.

It is in hypothesis generating (rather than in hypothesis falsification) that one cultivates multiple perspectives and possible worlds to match the requirements of those perspectives. [69]

Gardner argued similarly for the crucial perspective to be gained from the humanities:

"... by absorbing, through literature, religion, psychology, sociology, drama and the like, the hopes, fears, aspirations and dilemmas of (one's) people and of the species." [70]

Beyond WICS --

WICS is a demanding profile, and yet across expert resources, descriptions of mature creativity include some additional important specificity:

Teams --

In the past decade in particular, it is commonly held that learning to be creative within a team represents a fundamental element of maturing creative capability.Innovation by nature is cross-functional; however, that can amount primarily to a division of labor. It contrasts with, for example, what Douglas Thomas and John Seely Brown referred to as a collaborative meeting of minds, with reference to modern teams as "collectives of purpose" (see context in box below).

Internal and external conditions --

The work of multiple thought leaders associates the mature creative process with both internal and external conditions that are robust in terms of: openness; flexibility, and complexity. [70-1]Social innovation thought and action leader, John W. Gardner, noted that making complexity productive requires a "tolerance" that is borne of "profound confidence" in one’s capacity to "bring some kind of new order" from "a wild profusion of ideas and experience.” [72] For most learners, such profound confidence is almost certainly a product of experience and development.

Support for Discernment --

Bruner (whose scholarly work of some eight decades addressed "creativity" in addition to cognitive learning theory and more) considered "discernment" the most important creative ability:"To create consists precisely in not making useless combinations and in making those which are useful and which are only a small minority. Invention is discernment, choice." [73]

Csikszentmihalyi, too, spoke of discernment as central, specifically with respect to the evolving state of the world:

"It is no longer possible for mankind to blunder about self indulgently ...

The most important challenge that confronts us now is learning how to assess the pros and cons of the fruits of our imagination." [74]

Style of Thought --

Pertinent to a trajectory of learning, Bruner also referred to a "style of thought" that distinguishes any discipline and that requires time and participation for absorption. (e.g., "function" within biology). For innovation, style of thought candidates might be "leverage" and/or "change by way of value.""Increasing experience with a subject may be necessary to bring the meaning of its style of thought "increasingly to light." [75]

Within a World of Constant Change --

Douglas Thomas and John Seely Brown have called for "a new culture of learning" -- beginning with formal schooling -- that cultivates the imagination for a world of constant change and where continuous learning is lifelong. [76]Summarized in the box just below, the "new culture" model reinforces the function of personally compelling purpose. It includes elements of overlap with the WICS model, but with different terminology and different emphases.

Cultivating Imagination In World of Constant Change --

In the new culture of learning, change is not only embraced, it's created. The new culture is about "how the imagination is cultivated to harness the power of almost unlimited resources to create something personally meaningful." The design for learning is built upon:

- Knowing -- which is "increasingly about knowing how to find and evaluate information on any given topic"

- Making -- which features hands-on learning and "requires deep and practical knowledge of the thing one is trying to create"

- Playing -- which involves: (i) the "ability to organize, connect, and make sense of things"; (ii) the organizing principle of a "leap" ... over the gap between the knowledge one is given and a desired end result; and (iii) a questing disposition.

Good questions are especially important, and peer-to-peer learning is integral, based on active engagement within "collectives of purpose" -- based on shared interests and opportunities.

"Students learn best when they are able to follow their passion and operate within the constraints of a bounded environment."

"The passion of the learner is the greatest source of inspiration but also the largest reservoir of tacit knowledge," and "(tacit understanding) relates most deeply to the associations and connections among various pieces of knowledge."

Power of Small --Throughout any version of scaffolding stages there can be emphasis on the power of small, while allowing for the possibility of "big" emerging. Consider:

- First, especially for beginners, but overall as well, even small ideas -- when they work or strike one as promising -- can be strong in experiential reward and in learning effect. (Also, there can be large leverage at small scale.)

- Second, as discussed above, mature creativity is demanding. Some students may be naturals, but in general, the channel of development is substantial. With this, a series of continually positive "just right" experiences should lead continually upward in development (given Csikszentmihalyi's argument that there is growth in every "just right" experience). Progress in discovering a compelling personal purpose is likely to support development and its pace.

- Third, in support of authentic experiences of the methodology, small avoids expecting big ideas "upon command."

Intelligibility does demystify the origins of ideas: "Good ideas are not conjured out of thin air; they are built from a collection of existing parts ..."

However, the expert resources argue that original thinkers are able to facilitate, but not will, creative outcomes. For example:

"The creative process is often not responsive to conscious efforts to initiate or control it. It is unpredictable, digressive, capricious. The role of the unconscious mind in creative work is substantial." [61-5]

“Innovative opportunities do not come with the tempest but with the rustling of the breeze.” [61-6]Abiding by the organizing principles can facilitate ideas (especially smaller ideas), including calling for acquiring a particular type of knowledge.

Plus, since innovation fundamentally is about producing value, students can draw upon their developing consciousness of innovation's forces (and methods) as they pursue activities that they might already be engaging. For example:

With volunteer activities, consider how to create more forcefully positive value. For example, leverage the resources of student talents and interests to create new value such as:

- Students who love reading/math could ~tutor younger students after school, perhaps including being trained in tutoring (which would make greater use of knowledge about tutoring).

- Others could make greater use of their existing technological savvy by supporting an older generation not as savvy -- for example, in tasks such as more nimble use of music playlists, using Skype, Facebook, basic video editing, etc. (all high in reward to "customers" and readily available from digitally-intuitive youth).

Fundraising efforts represent another example of activity already happening, where the same basic task of incorporating innovation's forces could be engaged.Throughout the engagement activity, emphasize learner consciousness of innovation's purpose, forces, practices, etc., and the experience of letting ideas arise, no matter how simple. That includes ideas that arise later; those ideas can be documented and built upon for a future occasion.

This particular approach of modifying existing types of activities fits with Drucker's view that: “Successful entrepreneurs do not wait until the muse kisses them. They go to work.” In other words, the foundation of innovation's work -- and of the economy overall -- is producing value. Any activity associated with producing value invites engagement of innovation's methods. [61-7]

If/when big ideas emerge, guide students to test them, make revisions ("iterate"), create a design for action (using the business model canvas), and when appropriate, go for it.

Overall, with time and intentional structures, the combination of intelligibility and practice can train the eye and day-to-day impetus for change by way of value, cultivate knowledge, personal purpose and strengths, creativity's internal conditions and discerning imagination, and more. Students could become more aware of opportunities for learning and practice outside of school, including online communities of practice and "collectives of purpose" (as phrased by Douglas Thomas and John Seely Brown).

Especially if intrinsic motivation takes hold, these young learners could help create fertile external conditions that support peers. In fact, they're likely to influence an innovation learning system itself and to do so in big ways.

See sketches of engagement-oriented progamming at this site's Applications page, for students of varying age:

- Youth

- Higher Education -- Social Innovation

C. Lever of Embedded Personalized Guidance

"If (young people) are to commit themselves to the best in their own society, it is not exhortation they need but instruction." [86]John W. Gardner

With the prototype principles illuminating the fit of innovation practitioners' response to the human value for purpose -- larger than the self but personally compelling -- an innovation learning system provides a leverage point for developing both innovation capability and personal purpose.

Indeed, it's noteworthy that the type of scaffolding described in the sections just above resemble a process for discovering purpose that Damon discerned from his research among youth.

A Process -

Damon found not only similarity across individuals in the benefits of discovering personal purpose (including "a prodigious amount of extra positive energy"), he also found similarity in the type of process that had unfolded in discovering purpose and committing oneself to it. [80]Damon outlined a sequence of twelve steps, listed below, that he found to characterize the development of purpose among these youth. If support associated with learning about innovation is substituted for (or added to) the steps that feature support from immediate family and persons outside the immediate family (steps 1, 2, and 6), there is interesting resemblance between a principles-based process for learning about innovation and the process that led youth to make long-term commitment to an inspiring purpose.

- Inspiring communication with persons outside the immediate family

- Observation of purposeful people at work

- First moment of revelation: something important in the world can be corrected or improved.

- Second moment of revelation: I can contribute myself and make a difference

- Identification of purpose, along with initial attempts to accomplish something

- Support from immediate family

- Expanded efforts to pursue one's purpose in original and consequential ways

- Acquiring the skills needed for this purpose

- Increased practical effectiveness

- Enhanced optimism and self-confidence

- Long-term commitment to the purpose

- Transfer of the skills and character strengths gained in pursuit of one purpose to other areas of one's life. [81]

Examples of the mapping --

Consider the fit of Damon's process of steps for discovering purpose with the immediately preceding sections on "Intellgiility" and "Engagement":

Steps 1-3 were addressed under the "Intelligibility" section above, including the following quote and comments:

"Humans can observe and/or be shown how activities of humans have changed the environment, fostering realization that other people may be able to also bring about change ... A sense of what has been done helps lead to a sense of what might be done as well as an appreciation for the kinds of established constraints that might affect imagined changes." [44]

Intelligibility's combination of unifying concepts and varying types of examples, especially in combination with the pedagogical power of "stories," supports early connections to students' authentic interests (or the vicinity). Learners are encouraged to reflect on the types of real-world innovation examples that appeal to them (e.g., considering favorite examples, appealing roles, etc.), where examples can include the example of youth-driven applications of varying scale.

Intelligibility facilitates understanding common types of innovation variation, in support of personal connections:

- This includes not only variation with respect to offerings (e.g., type of value offered) and intended societal benefits (e.g., "profit vs. planet vs. people").

- It also includes multiple types of variation in practitioner style and roles. As just one example, one resource describes ten innovation "personas," emphasizing that there is more than one productive personal style of attunement to, and engagement with, innovation's purpose. Ten different personal orientations (e.g., the anthropologist, the experimenter, the convener, the cross-pollinator) are associated with the same fundamental sensing of "sharp edges" of offerings "crying out for improvement." [81-5]

Plus, innovation's principles help students see how the methodology relates to other types of methodogies and societal functions (as described under "Intelligibility"). This explication can support understanding of personal leanings that do not call for direct use of innovation's methods -- in part by clarifying how methodologies relate and in part by articulating the overarching imperative for innovation's societal effects in the 21st century (with most everything relating).

The closer examples can get to students' authentic interests (even latent or seedling interests), the more likely it seems that the learning will be received as compelling "value." Even progress in a personal sense of direction is likely to be valued.

As an example of a tool that draws upon innovation's "Intelligibililty" as a type of support for personal connection that resembles steps 1-3 of the common youth process that Damon observed, see the sketch for a searchable gallery of innovation examples at this site's separate page for Learning Applications.

Steps 4-10 ("I can contribute myself" through "Enhanced optimism and confidence).

Steps like these were addressed under the "Engagement" section, within a multi-year process of scaffolding.Hands-on experiences support a whole different type of exploration of innovation's varying ends and means. These experiences allow for unique qualities of feedback and discovery, which can support productive further exploration and/or development of purpose.

Both empowerment from the methods and support within hands-on learning (e.g., from teams and students' learning community) were described as fundamental to trajectories of learning about innovation, which includes purpose development:

- Within every hands-on experience, there is opportunity for new perspective regarding personal connection in terms of both purpose and medium of expression. Like a theatrical production, with roles that extend well beyond lead actors (to lighting, music, stage sets, costumes, marketing, etc.), the roles involved in conceiving, designing, and producing change-catalyzing value tend to be many and varied. There is enough value in a compelling purpose, or venture, to extend to many "practitioners."

- The nature of the collective effort also provides an example of how broad access to principles-based innovation instruction might add to, or substitute for, the effect of the family support identified in Damon's process (as might positive customer response).

- Broad access and participation also can generate creativity's fruitful external conditions (openness, flexibility, complexity), in support of individuals' fruitful internal conditions (again, openness, flexibility, complexity). To the extent that purpose discovery represents or resembles a creative process, these conditions themselves provide support for that process.

With repeated experiences over time, the combination of hands-on practice and deepening understanding of innovation's essential purpose and forces can provide continuing fodder for reflecting on personally compelling purpose.

- That includes support for asking questions -- gaining the type of perspective that allows for productive questions -- which can further support progress in personal direction. For example, the questioning can facilitate other types of experience (e.g., decisions about internships, elective courses, summer and extra-curricular activities), all of which can contribute to continuing purpose development and also to more informed approaches to planning for higher education.

- Increasingly linked to career navigation, this includes growing awareness of the types of personal strengths (including many which may not have been pertinent within academic work) that can support a developing sense of direction. For example:

- What types of value do I like to help create and/or put out into the world (or into my community)? What do I think can and should change in the world? What types of changemaking roles have I gravitated toward? What do these roles tell me about my strengths? How does all of the above fit into the economy/society and workforce?

- If I lean toward a "planet/sustainability" category of purpose (for example), do I prefer innovation's direct means of addressing that purpose or an indirect, pipeline means (e.g., advancing knowledge via methods of science/research, advancing technical capability via methods of invention/technology)?

Steps 11-12 ("longer term commitment" and "transfer of skills and character development to other areas of one's life") represent the element of power that a personal connection to purpose lends to maturing innovation capability, for robust personal and societal effects.

Echoes of, and response to, John W. Gardner --

In sum, principles-based innovation instruction features the call for, and value of, personal connection to the larger social enterprise. It can be viewed as a response to John Gardner's 1963 call to action, which remains utterly relevant today:"(W)e must help the individual to re-establish a meaningful relationship with a larger context of purpose. … (O)ne of the reasons young people do not commit themselves to the larger social enterprise is that they are genuinely baffled as to the nature of that enterprise. … They do not see where they fit in. If they are to commit themselves to the best in their own society, it is not exhortation they need but instruction. … We must also help the individual to discover how such commitments may be made without surrendering individuality." [86]

The last sentence might be rephrased: We must also help the individual to discover how much energizing enrichment and meaning there is in committing themselves to the best in their own society.It's significant that an innovation learning system, grounded and connected by high-quality organizing principles, might support the discovery of commitment as forcefully positive value (the opposite of surrendering individuality).

Indeed, the scaffolding of purpose may represent an embedded secret sauce within the scaffolding of innovation understanding:

- First, the subject of innovation provides a natural instrument for purpose exploration.

Learning experiences are like visiting a bridge that connects schooling's structure of academic disciplines (along with students' knowledge of anything and everything) with the economy and society's structure of producing value for collective benefits. Regular visits to this bridge involve repeated exposure to, and interaction with, the context of societal purpose, which can begin at the scale of a community of any size (e.g., a classroom community).

A trajectory of experiences can include learning enough to ask increasingly productive questions, which can benefit other types of support for purpose development and post-secondary navigation, such as internships, elective classes, extracurricular opportunities, and more.

- Second, as discussed under Part Three, below, the compelling value of a sense of direction gives rise to learning overall, and it integrates the learning.

It both contextualizes and personalizes academic work, including innovation capability (or a different methodology), all of which becomes a potential resource for acting on the purpose.

The meaning of a sense of direction provides both leverage and integration for developing depth and breadth of knowledge and skills.

This overall possibility contrasts with a status quo where:"We mainly train [adolescents] to be consumers -- of abstract information, entertainment, and mostly useless products -- with too little regard for concrete, active engagement with the environment."[86-5]

Again, innovation instruction's embedded personalized guidance seems to fit with a 2010 statement of strategy expressed at the web site of (U.S.) Council of Chief State School Officers, which described providing for:

- What every student should know (indicated by the Common Core State Standards).

- What each student should know (a personalized experience of the standards).[87]

It fits too with an innovation model for "maximal value," which emphasizes an ever-improving match between customer interests and global resources. Within the model, maximal value is realized when value is customized for every individual customer (N=1) by drawing on a global span of resources (R=G).[88] As discussed in the section just below regarding the special value of purpose, research has indicated that student discovery of purpose brings an energy and focus to academic work and to learning whatever is needed.

"Purpose gives rise to learning." [25-5]

Robert Quinn

In the 21st century, it's timely that the value of personal purpose -- larger than oneself but personally compelling -- has become increasingly visible, including the value of development among youth. That's because 21st century society needs the force of personal connections to purpose. It's an opportunity for win-win.

The visibility of purpose has been associated in part with the new field of positive psychology. For example, in co-founding the field, research psychologist and past president of the American Psychological Association Martin Seligman established a theory of "well-being," which speaks to what humans value most fundamentally (what free people will choose; "uncoerced choice"). "Meaning/Purpose" is included in the theory's set of five categories of experience, each of which is argued to be valued "for its sake alone":

- positive emotions

- engagement (of signature strengths)

- positive relations

- meaning (engaging strengths toward a purpose larger than oneself)

- achievement (for the sake of achievement alone) [3]

Meaning/purpose, in fact, represents a type of pinnacle category within the theory: Seligman relates the category of positive emotions to the "pleasant life," the categories of engagement, relations, and achievement to the "good life," and the category of meaning/purpose to the "meaningful life." (Having all five elements is associated with the "full life.")

Among Youth --

For youth in particular, support for purpose development has become newly visible as an active quest, based in part on the view that adolescence is "the proper period in life to begin such reflection."[18] This quest contrasts with a status quo in which purpose has been shown to be valued by most youth but largely elusive. Advocates argue that it is learnable -- indeed that developing or discovering it "has been a good deal harder than it should be." [15.5]William Damon, in particular, has provided a leading voice in youth-focused research regarding purpose and its effects, including leading the "Stanford Youth Purpose Project," with a nationally representative sample of U.S. high school students.

Consonant with Seligman's theory of well-being, Damon argues:

"The disposition toward purpose has been bred into (humans). [4] ... There's a universal yearning for the meaning of a sense of positive, forward direction." [5]

Based on his research with youth, Damon notes that this personalized sense of direction "is not necessarily career, but it's deeper than grades and awards." It speaks to the "why" of schooling (something Elon Musk has lamented as missing in the U.S.). Damon explains:

"[Purpose] speaks to an ultimate concern, larger than the self, a deeper reason for immediate goals and behavior. It speaks intrinsically to:

- Why am I doing this?

- What does it matter?

- Why is it important?" [6]

In providing a response to schooling's "why," purpose brings an energy and focus that contextualizes and integrates academic work:

"Only when students discover personal meaning in their work do they apply their efforts with focus and imagination." ...[7]

"Goals are integrative." [9]

"It's not simply academic motivation in the conventional sense. Rather, purpose behind the requirements. Why strive to learn and use the work in a masterful and ethical way?" [8]

"Only a long view fueled by energetic purpose can build and sustain capacities that will be needed."[10]

Similarly, from Robert Quinn, an organizational psychologist whose work includes schooling:

"The capacity to learn and create emanates from genuine commitment to purpose. When we really care we are willing to fail our way to success. In this process, we see and do things no one else does. ... Purpose gives rise to learning ..." [25-5]

It's further significant that purpose can contextualize a student's academic work because, unlike student/human value for purpose, academic work generally is not valued for its sake alone. In Why Students Don't Like School, cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham explains: "We're naturally curious, but we're not naturally good thinkers."[30] Academic work may be good for you, but often is not experienced as "good." For example: