Prototype: Innovation's Organizing Principles

This page elaborates upon each of the principles included in the site's prototype set of innovation's organizing principles. Selected sources are included throughout the elaboration. Also, the site's separate Feasibility page provides a narrative account of sources associated with initial questions such as: What is innovation exactly? Why does it matter? How does it work?

The summary of the prototype principles, just below, is followed by elaboration of each principle.

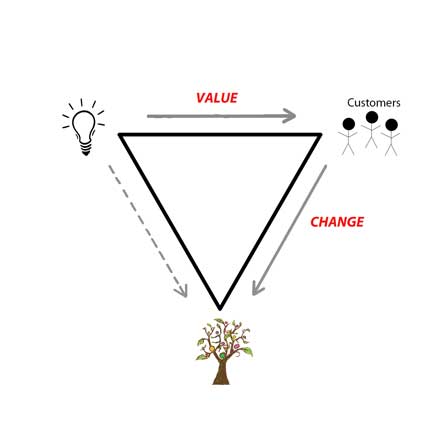

For the purpose of catalyzing the change of more value, or yield, from the same resources (e.g., yield in terms of "profit, planet, and/or people"):

- Principle #1 -- Innovation's change catalyst is compelling new "value," beginning with the value to practitioners of compelling purpose.

- Principle #2 -- Innovation's catalyst is forcefully positive

- Principle #3 -- Innovation's essential creative structure is hypotheses

- Principle #4 -- Innovation's hypotheses amplify a force of integration

- Principle #1 -- Innovation's catalyst is compelling new "value"

First, innovation's practitioners respond to the value of compelling purpose:

- Innovation's prime force occurs when practitioners respond to the value of a compelling purpose, associated with a picture of possibility about creating new value for others and putting it out into the world. [5]

- The compelling purpose, or picture of possibility, features the combined value of:

- "It matters" -- The potential new value for customers, and/or its societal effects, fits with a practitioner's driving interests and beliefs about what matters.

- "It's empowering" -- The possibility is grounded in knowledge. More specifically, it's grounded in new connections of existing knowledge, which represent hypotheses (either explicitly or implicitly) about "what could be" as a forcefully positive type of new value to others and "how" to put it out into the world.

- For example:

- When Google's co-founders made a scientific discovery about the reality of Internet link dynamics, they connected this discovery to other types of knowledge for the innovation hypothesis of: "We should use it for search." The possibility compelled them to leave their doctoral study for the purpose of developing a unique new search engine offering and putting it out into the world.

- As Wendy Kopp put it upon connecting the knowledge that led to her conception, as a college student, of Teach for America: "How could this not already exist? ... We (new college graduates) would jump at a chance to be part of something that brought thousands of our peers together to address the inequities in our country and to assume immediate and full responsibility for the education of a class of students." [6]

- The force of compelling purpose can extend throughout an organization (new or established), with the response of creative engagement from many different roles."[7] For example:

An article about Facebook quoted a vice president “who was doing a master’s in artificial intelligence” and initially thought Facebook would be a waste of time: "And the interview completely changed my mind. I saw the vision. I came in, and I saw it on a whiteboard."[8]

Then customers respond to the value of a compelling new offering:

Practitioners only propose new value. Innovation's change relies on positive customer response to the value that practitioners offer.

Practitioners only propose new value. Innovation's change relies on positive customer response to the value that practitioners offer.

- Customers are innovation's gatekeepers of change. [9]

- This dynamic calls on practitioners to be "inner-driven and other-focused" as they integrate the force of personally compelling purpose with innovation's separate force of compelling new value in the eyes of customers. [9-5]

- Practitioners must connect in one way or another to what customers care about.

- In some cases, practitioners may connect by caring about the same thing as their customers.

- In other cases, it may be a whole different type of value that matters to practitioners (e.g., environmental sustainability, wealth, education), but a connection is made by offering value that is compelling to customers.

- When customers find compelling value in a new offering and respond by adopting it, this response is fundamental in enabling practitioners to continue producing it.

- The production of new value takes place throughout a society's commercial and social production systems, where:

- organizations of widely varying types (both new and established)

- use resources of widely varying types (human, natural, knowledge, etc.)

- to produce value of widely varying types (from container ships that transform an entire industry to daycare for pets).

- It's when production of a new offering makes more fruitful use of existing resources that innovation's actual change of resource leverage occurs. "An innovation is a change in market or society."[9-8]

- For any given offering, there may be multiple customer segments, with each segment needing to respond.

Resulting value to society is the reason innovation matters:

- When innovation's practitioners imagine a way to create greater value from the same resources and customers respond, the change that matters most is at a societal level.

- "An innovation is a change in market or society. It produces greater yield for the user, greater wealth-production for society, higher value or greater satisfaction."[10-4]

- "Of course we know that … innovation is an economic, not a technical term."[10-5]

- Traditionally, the societal benefits of a shift to more fruitful use of resources has been measured in monetary terms, associated with standard of living. For example, speaking to wealth in the context of an overall economy:

- Peter Drucker expressed in the late 20th century: "Whatever changes the wealth-producing potential of already existing resources constitutes innovation." [10]

- And Jean Baptiste Say expressed nearly two centuries prior: "(T)o create objects which have any kind of utility, is to create wealth; for the utility of things is the ground-work of their value, and their value constitutes wealth. …(T)here is a creation, not of matter, but of utility; and this I call production of wealth." [10-6]

- However, Drucker was a pioneer in noting that "the purpose to which the resources are dedicated need not be what is traditionally thought of as economic."[10-1] "Wealth" can be conceptualized differently, and indeed the 21st century features three categories of broad purpose, each with its own societal-level benefit:[10-2]

- "Profit" -- The traditional purpose of producing more total economic value, measured in monetary terms as Gross Domestic Product (GDP), from the same resources serves as the primary indicator for the collective benefit of standard of living. (Note, GDP is an imperfect measure for standard of living; in particular, it doesn't indicate variation within a society -- only the overall level.)

"Planet" -- Producing value that functions to preserve environmental resources contributes to the collective benefit measured as environmental sustainability (or "reducing unsustainability").[10-3]

"Planet" -- Producing value that functions to preserve environmental resources contributes to the collective benefit measured as environmental sustainability (or "reducing unsustainability").[10-3]

- "People" -- Producing more quality of living from the same resources (e.g., more learning, more meaning, more positive relations) has been measured at a collective level predominantly in terms of "well being."

- Any particular new offering could support advances in multiple "P"s. Or an offering could advance one category with little effect on, or even reversal of, another.

For example:

- Value from a new clean energy offering that is met with strong customer response could support both environmental sustainability ("Planet") and GDP ( "Profit"). Indeed, there is an argument that the power of the commercial marketplace and business is necessary for creating a sustainable world, including (and especially) offerings in the form of system-level changes.[11]

- An effective non-profit educational organization could produce the value of vastly more learning from the same essential resources (e.g., via online access that is free and universally available, enabled by a ~fixed pool of philanthropic dollars). Such a large advance in total well-being ("People") would have little or no direct effect on GDP ("Profit") given no production of financial value. However, it might have a large future effect on GDP.

- In the 21st century, the three "P" categories reflect a context of substantially increasing global population along with finite natural resources. It's a context that establishes a significant and urgent new level of need for innovation's change of more fruitful use of resources. The categories are not new as societal ends; they're newly visible. [11-1]

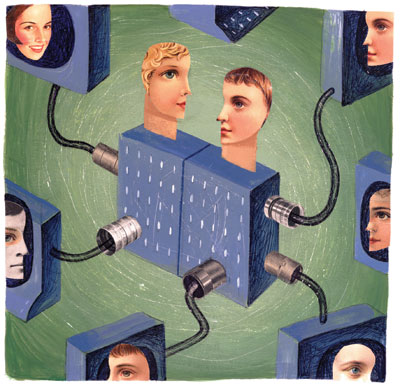

In sum, innovation's force of value creates a type of chain reaction of response:

- First, practitioners respond to the value of compelling purpose.

- Then customers respond to the value of a compelling new offering.

- Then innovation's change of more fruitful use of resources allows for advancing collective value to society.

- Principle #2 -- Innovation's Catalyst is Forcefully Positive

The type of new value that can catalyze innovation's change is forcefully positive

- Innovation's power is a function of the human pull to perceived value.

- For practitioners and customers alike, value can be like a positive magnet.

- Not all value exerts the same force, but especially for what is valued most, the human pull to perceived value may represent a force of (human) nature. [12]

For innovation practitioners, the forceful value of purpose

- Practitioner purpose is associated with the psychic reward, inspiration, engagement, and/or meaning that supports innovation's version of uncertain and typically demanding work, including demands of perseverance.

- "(W)hen all is said and done, innovation become hard, focused, purposeful work making very great demands on diligence, on persistence, and on commitment. If these are lacking, no amount of talent, ingenuity, or knowledge will avail. ... Successful innovators look at opportunities over a wide range. But then they ask, 'Which of these opportunities fits me, fits this company, puts to work what we (or I) are good at and have shown capacity for in performance?' ... Innovators must be temperamentally attuned to the innovative opportunity. It must be important to them and make sense to them. Otherwise they will not be wiling to put in the persistent, hard, frustrating work that successful innovation always requires."[5]

- A neuroeconomist described In 2013:

"... new studies showing that doing something with purpose causes the brain's reward circuits to activate. As a result, the purpose of what we do is directly related to how engaged we are at work." [13]

- Similarly, intrinsic motivation is viewed as fundamental to creative practice.

"A creative product is never random or arbitrary; it must be true to something deeply sensed or felt within the person." [14]

- Purpose fits into the broader value of "well being," or flourishing, which has been argued as among the most forcefully positive types of value. [15]

- According to well-being theory, there are five fundamental categories of value to which humans respond "for its sake alone." With these categories, no incentive other than the value itself is needed. There is "uncoerced choice" to respond.

- The five categories are: Positive Emotions, Engagement(of strengths), Positive Relations, Meaning(connection to a purpose larger than the self), and Achievement (when it is for the sake of the achievement alone).

- In the best of cases, innovation's practitioners are responding to the value of "work worth doing for the sake of meaning and engagement alone."

Forcefully positive even if context is problematic

- Innovation's value to customers is forcefully positive even within a context that is problematic (e.g., for a public health problem of unhealthy eating, an offering of new value might be healthy food that customers find worth eating for its good taste alone).

- In fact, within problematic contexts, the new value may need to be especially positive if it is to catalyze sustained customer response.

Pertinent to most every human and social exchange

- Forcefully positive new value as a catalyst for innovation's change of more fruitful use of resources has been called pertinent to "all (human experience) except that which could be called existential, rather than social." [16]

- The span of possibilities for new value has been described, for example, as supporting customers in their "jobs to be done" -- from transportation to mating, learning, being entertained, staying healthy, being a good citizen, and so on.

- For new offerings related to science alone, a 2012 edition of "Popular Science" demonstrates wide variation within offerings judged by the magazine as the top 25 of the last 25 years. Examples range from a company's seedless watermelon to Apple's iPhone and the Mars rover "Curiosity."

- Some customers represent an organization (a business, school, city government, etc.) and its jobs to be done.

- The possibilities for creating new value, toward more yield from the same resoources, extends across all dimensions of human life and all economic sectors (social, public, and commercial), industries, organization types and sizes, etc.

Pertinent at any scale --

- Whereas the label "innovation" is associated with transformative change that is large in scale, innovation's forcefully positive value can be harnessed to catalyze change at any scale.

- For example, at scale as small as a single classroom or lunchroom or household, etc., if "practitioners" find compelling value in a purpose that involves offering others forcefully positive new value (e.g., a means to recycling that catalyzes customer response), the offering can produce collective new benefits for that community.

- Small-scale change typically would not be labeled "innovation." However, the same fundamental responses to forcefully positive value apply.

- Additionally, at any scale, innovation's force of value can catalyze different amounts of leverage.

- One sample set of categories for amount of leverage features three innovation adjectives:

- incremental

- evolutionary

- disruptive [16-5]

Forcefully positive but morally neutral

- At each point of innovation's chain reaction of response, "value" is subjective -- in the eyes of practitioners and/or customers -- and not necessarily virtuous.

For example, for the collective benefit of economic value ("Profit"), where an overall economy features widely varying types of offerings:

- Each offering contributes in the same monetary way to GDP's association with the collective societal benefit of standard of living. It's the same currency of contribution for every industry and type of offering, from pornography to oil, agriculture and schools.

- Even offerings that intentionally "dupe" customers, as long as the duping is legal, can sustain a shift in total "Profit" value (GDP) from the same resources if customers sustain adoption of the offering.

- At the same time, Nobel Prize recipient Daniel Kahneman argues for the importance of what might be thought of as innovation ethics or wisdom, calling for "responsible creativity."[17]

Needed customer response to value's force can vary

- Innovation's change of resource leverage can call for differing customer response to an offering.

- In particular, some offerings may need to catalyze change in customer behavior and/or capability -- beyond transactions. [18] These needed changes can be prominent for some offerings, especially those associated with advances in "Planet" or "People":

For example, a new type of classroom tool that aims to generate greater student learning/capability ("People") calls for teacher and student experiences of the tool that are forcefully positive enough to catalyze the behavior of engaged use of the tool and useful enough to catalyze the change in learning.

For example, a new type of classroom tool that aims to generate greater student learning/capability ("People") calls for teacher and student experiences of the tool that are forcefully positive enough to catalyze the behavior of engaged use of the tool and useful enough to catalyze the change in learning.

- Similarly, whereas a newly valuable type of exercise offering may lead to sustained transactions, it only benefits public health ("People") if it is used -- if it catalyzes change in behavior.

- For some offerings, catalyzing change in behavior represents the fundamental nature of customer adoption/transactions, as with response to recycling services ("Planet").

For the change of advancing GDP ("Profit"), sustained transactions generally is the sufficient customer response. However, some commercial offerings too may call for additional types of response, as either an integral or optional aspect of adoption:

For the change of advancing GDP ("Profit"), sustained transactions generally is the sufficient customer response. However, some commercial offerings too may call for additional types of response, as either an integral or optional aspect of adoption:

- For example, within the "shared economy," adopting an offering like AirBnB or Uber can call for change in customer behavior (e.g., new expressions of trust) as a fundamental element of transactions.

- An offering that applies new technology may call for the customer response of learning, with change in customer capability.

- For offerings with multiple customer segments, the needed type(s) of response can vary among the segments.

- Principle #3 -- Hypotheses are essential creative structure

Innovation's hypotheses represent the methodology's essential creative structure

- Whether implicitly or explicitly, it's innovation's two types of hypotheses that form a picture of possibility:

- "What could be" as new value for others

- and "How it could become" an offering that catalyzes customer adoption and a sustained advance in the total value produced from the same resources.

Like hypotheses of science & invention

- Innovation's practitioners, like practitioners of the methods of science and invention, form hypotheses by making new connections of existing knowledge.

- They engage imagination that features "the ability to see possible ... connections [of existing knowledge] before one is able to prove them in any way... " [19]

- "Good ideas are not conjured out of thin air; they are built out of a collection of existing parts. [19-5]

- With all three methodologies (innovation, science, and invention), hypotheses serve as the essential creative structure:

- All three methodologies can be viewed as "evaluative-generative."[20] Practitioners engage a range of thinking skills (e.g., analytical, creative, and practical) to process knowledge toward a new purposeful connection, even if processing is experienced as effortless.[20-5]

- Practitioner discernment is fundamental to recognizing promising new connections. [21]

- Effective hypotheses result in making "more" of the existing knowledge that is newly connected.

Different from hypotheses of science & invention

- In making more of existing knowledge, it's the nature of "more" -- of the advance, or purpose -- that represents the key departure for hypotheses of science, invention and innovation. The point of departure is direct purpose, which leads to associated fundamental differences such as medium of expression, gatekeeper of change, and more:

- Hypotheses of science, for the purpose of advancing knowledge, address "what is." These hypotheses feature valid and reliable new connections that advance understanding of an existing formal system of reality, typically associated with the domain of an academic discipline.

For hypotheses that pass the scientific test of being valid and reliable, the medium of expression for change is argument geared to the scientific methods.

- Hypotheses of invention, for the purpose of advancing technical capablity, address "what could be technically." Actionable connections of knowledge, typically from the broad domain of applied math and science, are expressed as technical demonstration.

- Hypotheses of innovation, for the purpose of realizing the societal benefits of resource leverage, address "what could be" as forcefully positive new value for customers and "how it could become" an offering that catalyzes the societal-level change of more value produced from the same resources.

- The medium of expression is the action of producing value (in the form of offerings) within the domain of commercial and social production systems.

- A key gateway test of innovation's hypotheses is customer response in the marketplace, and the ultimate test is the result of making more fruitful use of the same resources by producing the offering (where fruitfulness is determined by innovation's ultimate societal benefits).

- Innovation hypotheses may be tested by using methods of science (e.g., experiments). However, truth matters differently for innovation's purpose (vs. the purpose of science). Investing resources in a false innovation hypothesis means wasting resources, since a false hypothesis would fail in the course of action. Testing matters to the extent that resources matter. (Resource waste isn't limited to money. It can include time and energy, plus the opportunity cost of not channeling the resources to a "true" hypothesis, etc.)

Innovation hypotheses are for purposeful action

- Innovation's hypotheses are like a design for action. They allow for increasing focus regarding a picture of possibility.

- One common framework for considering combined "what" and "how" hypotheses -- whether at the stage of initial ideas or as concrete details -- is the fill-in-the-blanks "Business Model Canvas" shown below.

- This canvas depicts the fundamental system of producing value. Even though "business" is in the name of the canvas, the system depicted is pertinent to any organization using resources to produce value -- commercial, social, global, or a high school service organization with zero budget, only human resources.

- The central box for "customer value proposition" represents "what could be as new value," with the grey boxes representing fundamental "how" hypotheses.

- The right half of the canvas features an operation's customer-facing "front end," with the left half as the "back end."

- Each grey box could contain many hypotheses:

Varying practitioner pathways to innovation hypotheses --

- It's likely that all pathways to innovation hypotheses converge at the point of an overall canvas-like design for action, again whether implicitly or explicitly.

- The particular Business Model Canvas tool has assumed prominence among practitioners whose pathway to innovation hypotheses begins with new technical capability. (This includes professional development associated with the National Science Foundation.) For these practitioners, the canvas supports "customer development" -- e.g., hypothesizing about the types of customers who have unmet needs that can be addressed by the new technical capability. [21.2]

- Practitioners following different pathways still can make use of the Canvas. For example: For a pathway that begins by noticing an unmet need among particular customers, which leads to a "what could be" hypothesis about new value, the Canvas can serve as a tool for considering the fundamental set of "how" hypotheses that are involved in producing an offering.

- In general the Canvas provides a tool that can be used flexibly. For example:

- For organizing, conveying, and keeping track of innovation hypotheses.

- For fine tuning a system for producing a particular offering (e.g., assessing weak elements within an offering's existing canvas and then developing hypotheses for strengthening).

Cross-functional work integrated by force of value --

- In its depiction of a system for producing value, the business model canvas emphasizes that innovation's action is cross-functional, whether it's one person performing all of the functions or thousands.

- Throughout the functions, the "core value proposition" (what could be as new value for customers) provides the force of integration for all "how" hypotheses.

- However, since there often is a version of "customer" associated with each "how" hypothesis (e.g., a potential partner organization), innovation's fundamental force of value can pertain throughout the entire canvas.

For example --

-

When Google prepared to introduce its "what could be" superior search engine, its early organization knew it needed a crucial "how" hypothesis for "revenue streams" (the bottom-right box of the business model canvas). The result was to offer advertisers their own newly-conceived advertising value -- a way for advertisers to target their message and spending to particular customers. In Google's case, this "how" for revenue was related directly to the search engine's uniqueness.

When Google prepared to introduce its "what could be" superior search engine, its early organization knew it needed a crucial "how" hypothesis for "revenue streams" (the bottom-right box of the business model canvas). The result was to offer advertisers their own newly-conceived advertising value -- a way for advertisers to target their message and spending to particular customers. In Google's case, this "how" for revenue was related directly to the search engine's uniqueness.

Since a key part of the Khan Academy's purpose was to offer its library of learning videos for free to anyone anywhere, it too needed a hypothesis for revenue. Initially, it was a large donor (Bill Gates on behalf of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) that provided the "how" of revenue, as Bill Gates responded personally to the value of compelling purpose he found in the offering. As the Khan Academy took flight, the base of donors expanded, plus new types of "how" hypotheses for revenue included offering value to a range of partners: banks (for videos teaching about personal finance); testing organizations (for test prep videso) and more. Each revenue source was a type of customer, responding to value.

Since a key part of the Khan Academy's purpose was to offer its library of learning videos for free to anyone anywhere, it too needed a hypothesis for revenue. Initially, it was a large donor (Bill Gates on behalf of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) that provided the "how" of revenue, as Bill Gates responded personally to the value of compelling purpose he found in the offering. As the Khan Academy took flight, the base of donors expanded, plus new types of "how" hypotheses for revenue included offering value to a range of partners: banks (for videos teaching about personal finance); testing organizations (for test prep videso) and more. Each revenue source was a type of customer, responding to value.

-

For the founder of the Ocean Cleanup the "how" for catalyzing needed human resources for developing his prototype invention into a marketable offering featured a TED talk in which the founder conveyed his "what could be" hypothesis regarding a way to clean tiny plastic particles from oceans, including early results. Hundreds of professionals on multiple continents responded to the value of this purpose by volunteering their high-level skills and knowledge, on a part-time basis, for months if not years. As of 2016, a fully-developed offering was installed for its first paying customer of the government of Japan.

For the founder of the Ocean Cleanup the "how" for catalyzing needed human resources for developing his prototype invention into a marketable offering featured a TED talk in which the founder conveyed his "what could be" hypothesis regarding a way to clean tiny plastic particles from oceans, including early results. Hundreds of professionals on multiple continents responded to the value of this purpose by volunteering their high-level skills and knowledge, on a part-time basis, for months if not years. As of 2016, a fully-developed offering was installed for its first paying customer of the government of Japan.

-

Another non-profit, Teach For America (TFA), was built on the primary "how" hypothesis for the resource (on the left side of the canvas) of a high-caliber teaching corps of new college graduates by offering these graduates the value of purpose/meaning (a two-year experience of teaching in high-poverty schools). Founder Wendy Kopp recognized that her Princeton peers were taking jobs on Wall St. because "they couldn't think of anything better to do" and “We would jump at a chance to be part of something that brought thousands of our peers together to address the inequities in our country...” What's more, the value of this teacher resource to school districts meant that they agreed to hire TFA teachers directly, which provided a channel of distribution for TFA that absorbed the cost of their key resource and thereby reduced the need for revenue.

Another non-profit, Teach For America (TFA), was built on the primary "how" hypothesis for the resource (on the left side of the canvas) of a high-caliber teaching corps of new college graduates by offering these graduates the value of purpose/meaning (a two-year experience of teaching in high-poverty schools). Founder Wendy Kopp recognized that her Princeton peers were taking jobs on Wall St. because "they couldn't think of anything better to do" and “We would jump at a chance to be part of something that brought thousands of our peers together to address the inequities in our country...” What's more, the value of this teacher resource to school districts meant that they agreed to hire TFA teachers directly, which provided a channel of distribution for TFA that absorbed the cost of their key resource and thereby reduced the need for revenue.

- At InnovationAgents.org, see more detail for each of these examples, including the knowledge connected within each hypothesis.

Innovation's purpose determines "pertinent" knowledge for hypotheses --

- Principle #4 -- Innovation's hypotheses amplify integration force

Whereas hypotheses of all types (not innovation hypotheses alone) reflect integration within and among the fundamental elements of cognitive processing, knowledge and purpose:

- Cognitive Processing -- Making a purposeful new connection of existing knowledge, no matter how effortless the conscious experience, draws upon intensively integrated cognitive processing:

- New connections integrate multiple ways of thinking and knowing (analytical, creative, and practical) and benefit from fertile conditions, including thematic internal and external conditions (e.g., openness, flexibility, and complexity). [25]

- Bruner used the expression "hypothesis generating" to represent such processing, which he linked to the thinking and knowing associated with the humanities:

"For, in effect, the humanities have as their implicit agenda the cultivation of hypotheses, the art of hypothesis generating.

It is in hypothesis generating (rather than in hypothesis falsification) that one cultivates multiple perspectives and possible worlds to match the requirements of those perspectives.

The process of generating effective new connections "is akin to the activities of the humanist and artist." [24]

- Moreover, for effective hypotheses, discernment is fundamental: "To create consists precisely in not making useless combinations and in making those which are useful and which are only a small minority. Invention is discernment, choice." [26]

- Knowledge --

It's not unusual for a newly perceived connection to integrate knowledge that has no obvious relation. For example:

- "The truly creative person is not an outlaw, but a lawmaker. They bring about new relatedness, connect things that did not seem previously connected, sketch a more embracing framework, move toward larger and more inclusive understandings." [23.1]

- Having studied creativity for over 30 years, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi noted that "(C)reative people ... love to make connections with adjacent areas of knowledge." [23.3]

- Purpose -- A methodology's distinctive purpose steers the processing of new knowledge connections:

- Direct purpose is the point of departure for hypotheses of science (to advance knowledge) versus invention (to advance technical capability) versus innovation (to advance resource leverage).

For *innovation* hypotheses, integration is amplified by virtue of many additional dimensions, such as:

- "What could be" is integrated with "How it could become"-- Within a single offering, innovation's complementary "what" and "how" hypotheses amplify integration:

- In Steve Jobs' words: "(T)here's the technical part of the equation and the business part, meaning the distribution, manufacturing, and so on. And then there's the human part. You just have to put the whole equation together." Jobs emphasized integration of the equation throughout the full span of an offering's development, using terms such as "deep collaboration" and "concurrent engineering." [28]

- In some cases, the technical part is tightly integrated with other parts of the "equation" (e.g., Google's early hypothesis for "how to generate revenue" from its search engine offering was linked directly to the offering's core value proposition of unique search results).

- The overall set of "what" and "how" hypotheses both modify and integrate widely differentiated, cross-functional work, whether it's all done by one person or by thousands.

- Hypotheses can be initiated by many different roles within an operation, incorporating different specialized knowledge and drawing on an array of personal strengths, all channeled to the shared purpose of a compelling picture of possibility.

- Extent of knowledge integration -- Knowledge integration in itself includes many dimensions:

- Every "what" and "how" innovation hypothesis calls for considering knowledge from multiple strands, levels, forms, etc.

- Since virtually all knowledge can be "pertinent" to innovation's overall purpose, the methodology could be said to integrate it all -- including across subjects, levels, and forms of knowledge.

- Any inclusion of academic knowledge may draw from multiple disciplines, sub-fields, etc., and may also be combined with ordinary or any other type of knowledge.

- In light of innovation's fundamental human/social dynamics, highlighted by customers as innovation's gatekeepers of change, John W. Gardner argued that the humanities provide valuable knowledge based on the particular human perspective to be gained:

"... by absorbing, through literature, religion, psychology, sociology, drama and the like, the hopes, fears, aspirations and dilemmas of (one's) people and of the species."[29]

- Indeed, innovation's ultimate integration may reflect the combination of knowledge about fast-changing technology, information, etc., with knowledge about the remarkably slow-to-change human brain (as the locus of response to value).

- The increasing consensus that the combination of knowledge depth (in a particular area) and knowledge breadth -- a combination sometimes expressed as "T-Shaped" -- is considered advantageous to making effective new knowledge connections seems especially pertinent to innovation's hypotheses. [28.5]

- Integrating Thinking with Action -- Described as "integrating and applying knowledge," innovation's hypotheses integrate thinking and action.[29.5] Plus, an initial design for action unfolds repeatedly:

- The integration of thinking and action continues day to day within the context of producing value for customers. It never really ends.

- For example, the results of prior thinking-action are integrated with hypotheses about opportunities for future action.

- Also, the integration of "overarching" and "contributing" hypotheses is constant as the continuing day-to-day work that supports an overall vision of "what could be" is suffused with ongoing "how" hypotheses.

- Integrating organizations with other organizations -- This integration is reflected in an offering's overall set of hypotheses. For example:

- The benefit of integrating with partner organizations is so fundatmental that the Business Model Canvas tool includes a standard "how" box for "Partners."

- Organizations throughout a chain of supply can amplify a force of integration:

- Supply-chain organizations might fit explicitly into another organization's Business Model Canvas as "Resources," "Channels of Distribution," or any other other element of the canvas.

- The more that there is shared and energized commitment to the "what could be" hypothesis of new value for end customers, the more that an overall chain of resources can be leveraged toward that collective purpose.

- Forceful integration might feature organizations from different sectors of the economy (commercial, social, public).

- Integrating Societal Ends (Profit with Planet with People) -- Innovation's categories of societal benefit address different dimensions of human life on this planet, but they're not naturally divided. Innovation's methodology can intentionally aim for integrative effects:

- Again, this is demonstrated by examples of clean energy offerings that advance both Planet and Profit. And again, there is an argument that the power of the commercial marketplace and business will be necessary for realizing a sustainable world.[11]

- Plus, the vast size of innovation's domain (an overall economy) and the variation within it (including all of its sectors -- commercial, social, and public) suggests that there is opportunity to better "integrate"/match workforce participants with societal ends and with specific types of purpose.

- Integrating Practitioner Paths & Personas -- As a methodology, there is integration of varying types of practitioner paths to innovation hypotheses (e.g., beginning with new technical capability versus focus on societal/market/industry dynamics) and also integration of practitioner "personas."

- Differentiated styles and processes all are integrated by innovation's organizing principles and can be combined within a given picture of possibility.

- For example, a co-founder of the design firm IDEO, has emphasized that there is more than one productive personal style of attunement to, and engagement with, innovation's purpose. Ten different personal orientations (e.g., the anthropologist, the experimenter, the convener, the cross-pollinator) are associated with the same fundamental sensing of "sharp edges" of offerings "crying out for improvement."[31]

- Integrating Models & Tools -- Innovation's core methods also integrate varying types of models and tools.

- There can be nimble selection and use of a treasure trove of innovation models and tools, based on fit within innovation's forces and methods (e.g., "disruptive" innovation's criteria could be integrated with the "lean startup" process).

- See a sample set of models and tools, grouped by differing functions, here.

Summary --

Again, a summary of the prototype set of innovation's organizing principles:

For the purpose of catalyzing the change of more yield from the same resources (e.g., yield in terms of "profit, planet, and/or people"):

- Principle #1 -- Innovation's change lever is new "value," beginning with the value to practitioners of compelling purpose.

- Principle #2 -- Innovation's catalyst is forcefully positive

- Principle #3 -- Innovation's essential creative structure is hypotheses

- Principle #4 -- Innovation's hypotheses amplify a force of integration

NOTES:

[5] For example:

Peter F. Drucker, in Innovation and Entrepreneurship, (HarperBusiness, 1985), p 138: "(W)hen all is said and done, innovation become hard, focused, purposeful work making very great demands on diligence, on persistence, and on commitment. If these are lacking, no amount of talent, ingenuity, or knowledge will avail. ... Successful innovators look at opportunities over a wide range. But then they ask, "Which of these opportunities fits me, fits this company, puts to work what we (or I) are good at and have shown capacity for in performance? ... Innovators must be temperamentally attuned to the innovative opportunity. It must be important to them and make sense to them. Otherwise they will not be wiling to put in the persistent, hard, frustrating work that successful innovation always requires."

John W. Gardner, in Self-Renewal, the Individual and the Innovative Society, (W.W. Norton & Company: New York, 1963), p 37, in chapter entitled "Innovation": "(Creative individuals) reserve their independence for what really concerns them -- the area in which their creative activities occur."

Similarly, creativity researchers have deemed intrinsic motivation as fundamental to creative work. See for example: Teresa M. Amabile, Creativity in context, (Westview Press: Boulder, CO, 1996).

This is borne out by accounts of innovation practitioners in compilations such as:

- David Bornstein, How to Change the World, Social Entrepreneurs and the Power of New Ideas, (Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 2004)

- John A. Byrne, World Changers: 25 Entrepreneurs Who Changed Business as We Knew It, (Portfolio/Penguin, 2011)

- Also, in recent years many personal anecdotes have been shared, such as a presentation by Steve Case, co-founder of AOL, in which he described feeling "gripped" by possibilities (for community) associated with futurist Alvin Toffler'sThe Third Wave. See video, Feb. 24, 2010, Stanford University, ecorner.stanford.edu.

[6] Wendy Kopp, One Day, All Children: The Unlikely Triumph Of Teach For America And What I Learned Along The Way, (Public Affairs: New York, 2001), p 6

[7] In one dense set of examples, the stories of twenty-five modern "world changers" feature a pattern of lead venturers catalyzing human energy and effectiveness within their organizations by way of: (i) attracting shared conviction in a picture of possibility; (ii) calling for ongoing shared engagement in realizing the vision. See John A. Byrne, World Changers: 25 Entrepreneurs Who Changed Business as We Knew It, (Portfolio/Penguin, 2011)

[8] Time Magazine, January 2011, “2010 Person of the Year”

[9] I first heard innovation depicted as "change by way of value" by Michael Crow, President of Arizona State University, in 2012 when he spoke as a guest at an Ashoka Changemaker Campus "Exchange," convened that year at ASU. http://ashokau.org/exchange/about/

[9-5] Robert E. Quinn, Change the World: How Ordinary People Can Accomplish Extraordinary Results, (Jossey Bass: San Francisco, 2000. Quinn describes the combination of being "inner-driven and other-focused" as the "fundamental state of leadership."

Also, related to the notion of other-focused, the fit of "empathy" within innovation's practice is highlighted by leading voices such as: IDEO (design firm) and Stanford d.school leaders with respect to the model of Design Thinking and the organization of Ashoka: Innovators for the Public.

[9-8] Drucker, 1985, p 27

[10] See the entire first section of this site's Principles - Sources page. Plus: From Peter F. Drucker, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, (HarperBusiness, 1985), p27:

"(Jean Baptiste) Say was primarily concerned with the economic sphere. But his definition only calls for the resources to be 'economic.' The purpose to which these resoures are dedicated need not be what is traditionally thought of as economic. Education is not normally considered 'economic' ... but the resources of education are, of course, economic. They are in fact identical with those used for the most unambiguously economic purpose such as making soap for sale. Indeed, the resources for all social activities of human beings are the same and are 'economic' resources. ... (Entrepreneurship) pertains to all activities of human beings other than those one might term “existential” rather than 'social.'"

[10-1] See immediately preceding footnote.

[10-2] Jeffrey D. Sachs, Building the New American Economy - Smart, Fair, & Sustainable, (Columbia University Press; New York, 2017). Sachs associates "sustainable development" overall with economic policy that focuses simultaneously on the issues of: promoting economic growth, promoting social fairness, and promoting environmental sustainability. p 7

[10-3] Andrew J. Hoffman, Finding Purpose, Environmental Stewardship as a Personal Calling, (Greenleaf Publishing Ltd: U.K, 2016).

Hoffman refers to "creating a sustainable world," which in effect combines the three societal P's. In asociation with these interrelated ends, Hoffman argues that the foundational means will require "a deep shift in our values that is on par with the Reformation, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, or the Digital Revolution." (p 71)

[10-4] Drucker, 1985, p 252

[10-5] Drucker, Managing in the Next Society, (St. Martin’s Press: New York, 2002), p 95

[10-6] Jean Baptiste Say, A Treatise on Political Economy, (1821), Book I, Chapter I

[11] For example, from Hoffman, 2016:

"The market is the most powerful institution on the planet, and business the most powerful entity within it." (p 41)

"If business does not lead the way toward solutions for an enironmentally sustainable, carbon-neutral world, there will be no solutions." (p 42)

"It does not require a 'green' mindset to see the opportunities. It requires a 'business' mindset." (p 47)

"The next iteration of sustainable business practices, moving from enterprise integration to market transformation, will establish new norms of social and environmental behavior on a global level, translate those norms to the national and local levels, and develop solutions that are systemic in nature, rather than collections of siloed approaches." (p 42)

See also video presentation at: Andrew Hoffman, Holcim (U.S.) Professor of Sustainable Enterprise, University of Michigan, presentation: "Finding Purpose: Environmental Stewardship as a Personal Calling," Dec. 6, 2016. Positive Links Speaker Series, Center for Positive Organizations, University of Michigan Ross School of Business, video: http://bit.ly/2ygQIcF

[11-1] The interrelatedness is not new. It is a level of attention that is new. As but one example of the type of new attention that has grown in visibility:

Within a 2007 panel discussion held at the University of Michigan, entitled, "Is Consumerism Sustainable?" the panelists concurred that "innovation" is the answer to sustainable development … "either gradually or by crisis." It is up to innovation to advance yield on natural resources to at least maintain the standard of living among developed populations while also improving the standard of living among developing populations. University of Michigan Erb Institute video archives, "Is Consumerism Sustainable?" (2007)

Jeffrey Sachs has added that innovation will not be enough; political change is required too.

[12] Knowledge about "value," on a fundamental level, seems surprisingly limited within the work of innovation's thought and action leaders. One seemingly pertinent resource is knowledge from the new field of positive psychology. For example, Martin Seligman refers to his theory of "well-being" as one representing five categories associated with "uncoerced choice" -- of value for the sake of their direct value alone: positive emotions, engagement (of personal strengths), positive relations, meaning, and accomplishment. See Martin E. P. Seligman, Flourish, A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being, (Free Press, Simon & Schuster: New York, 2011)

Seligman refers to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi's theory of "flow" with regard to the well-being element of engagement. See Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Flow : the psychology of optimal experience, (Harper Perennial: New York, 1991)

[13] See references at footnote 5 above.

[13-1] Paul J. Zak, from "The Drucker Exchange" blog, April 4, 2013, http://thedx.druckerinstitute.com/2013/04/purpose-of-purpose/

[14] Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, The Evolving Self: A Psychology for the Third Millenium, (HarperCollins: New York, 1993), p 62

[15] Martin E. P. Seligman, Flourish, A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being, (Free Press, Simon & Schuster: New York, 2011)

[16] Peter F. Drucker, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, (HarperBusiness, 1985), p27

[16-5] Soren Kaplan, "How One Insurance Firm Learned to Create an Innovation Culture," Harvard Business Review (hbr.org),

August 15, 2017

[17] Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow, (Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, 2011), p 100

[18] jThese ideas draw in part from Stephen Goldsmith, The Power of Social Innovation, (Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 2010). See this site's description of a "Social Differential."

[19] Jerome S. Bruner, Actual Minds, Possible Worlds, (Harvard University Press, 1986), p 13

[19-5] Steven Johnson, Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation, (New York Riverhead Books, 2010), p 35

[20] "Evaluative-generative" comes from Sir Ken Robinson, Out of Our Minds, Learning to Be Creative (Capstone Publishing: UK, 2011). Robinson described "medium of expression" as the mechanism for generativity.

[20-5] For a particularly comprehensive example, which builds on decades of collective scholarly work, see: Robert J. Sternberg, Wisdom, Intelligence, and Creativity Synthesized, (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003). In this model, the intellectual element of creativity is described as calling for analytical, creative, and practical thinking skills. For a range of sources, see this web site's Feasibility page (especially the section on Creativity).

[21] For example, see:

Jerome S. Bruner, On Knowing, Essays for the Left Hand, (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 1962), p 20: "To create consists precisely in not making useless combinations and in making those which are useful and which are only a small minority. Invention is discernment, choice."

William Damon, "The Education of Steve Jobs," Stanford University, Hoover Institution, Defining Ideas, 9-16-2011: "But any idiot can take risks. ...The essential question is not whether people can take risks but rather how certain people are able to discern when a particular risk is worth taking. In fact—and this is rarely appreciated by those in the media who observe successful entrepreneurship from the outside—well-prepared entrepreneurs generally do not experience their investments in innovation to be much of a risk. The key is their preparation, not their desire to gamble."

[21-2] For example, see:

Steve Blank, The Four Steps to the Epiphany, Successful Strategies for Products that Win, (Lulu Enterprises, Inc. 2003)

[21.5] Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur, Business Model Generation, (Self-published, 2009), p 1

[22] Frank H. T. Rhodes, "Sustainability: the Ultimate Liberal Art," The Chronicle Review, Volume 53, Issue 9, p B24

[22-5] Peter Thiel described the pertinence of "secrets" in: Peter A. Thiel, Zero to One (Crown Publishing Group: New York, 2014).

[23] Edmund Phelps, Mass Flourishing (Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 2013)

[23-1] John W. Gardner, Self-Renewal: The Individual and the Innovative Society, (Norton, New York, 1963), p 33

[23-2] Johnson, p 33

[23.3] Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Creativity - Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention, HarperCollins: New York, 1996), p 10

[24] Bruner , 1986, p 52

[25] Although this cognitive processing element draws upon a particularly dense set of sources, certain articulations summarized chunks of sources. For the way s of thinking and knowing -- "analytical, creative, and practical" -- the articulation draws in particular from Rober J. Sternberg's "WICS" model (Wisdom, Intelligence, and Creativity Synthesized).

For the set of thematic descriptors of internal and external conditions (openness, flexible, and complexity) the terms were repeated across many sources, including over time. For examples of overall sources, see this web site's Feasibility page (especially the section on Creativity).

[26] Jerome S. Bruner, On Knowing, Essays for the Left Hand, (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 1962), p 20

[27] "Collectives of purpose" describes the fundamental type of collaborative team in: Douglas Thomas and John Seely Brown, A New Culture of Learning, Cultivating the Imagination for a World of Constant Change, (Create Space: Lexington, KY, 2011)

[28]"The Entrepreneur of the Decade," Inc. Magazine, April 1, 1989

Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs (Simon & Schuster: New York, 2011), p 362

[28.5] The "t-shaped" concept refers generally to individuals each having in-depth knowledge and skills related to one area plus wide-ranging complementary knowledge and skills. Tom Kelley of IDEO Design was an early proponent. IDEO attributes the term and concept to McKinsey & Company. For perspective, see: http://www.ceri.msu.edu/t-shaped-professionals/

[29] John W. Gardner, On Leadership, (The Free Press: New York, NY, 1990), p 165

[29.5] Clayton M. Christensen and Henry J. Eyring, The Innovative University: Changing the DNA of Higher Education from the Inside Out, (Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, 2011), p 343, pp 368-369

[30] Wendy Kopp, A Chance to Make History, What Works and What Doesn’t in Providing an Excellent Education for All, (New York: Public Affairs, 2011)

[31] Tom Kelley, The Ten Faces of Innovation, (Currency Doubleday: New York, 2005)

Practitioners only propose new value. Innovation's change relies on positive customer response to the value that practitioners offer.

Practitioners only propose new value. Innovation's change relies on positive customer response to the value that practitioners offer.  "Planet" -- Producing value that functions to preserve environmental resources contributes to the collective benefit measured as environmental sustainability (or "reducing unsustainability").[10-3]

"Planet" -- Producing value that functions to preserve environmental resources contributes to the collective benefit measured as environmental sustainability (or "reducing unsustainability").[10-3]

For example, a new type of classroom tool that aims to generate greater student learning/capability ("People") calls for teacher and student experiences of the tool that are forcefully positive enough to catalyze the behavior of engaged use of the tool and useful enough to catalyze the change in learning.

For example, a new type of classroom tool that aims to generate greater student learning/capability ("People") calls for teacher and student experiences of the tool that are forcefully positive enough to catalyze the behavior of engaged use of the tool and useful enough to catalyze the change in learning.  For the change of advancing GDP ("Profit"), sustained transactions generally is the sufficient customer response. However, some commercial offerings too may call for additional types of response, as either an integral or optional aspect of adoption:

For the change of advancing GDP ("Profit"), sustained transactions generally is the sufficient customer response. However, some commercial offerings too may call for additional types of response, as either an integral or optional aspect of adoption:

When Google prepared to introduce its "what could be" superior search engine, its early organization knew it needed a crucial "how" hypothesis for "revenue streams" (the bottom-right box of the business model canvas). The result was to offer advertisers their own newly-conceived advertising value -- a way for advertisers to target their message and spending to particular customers. In Google's case, this "how" for revenue was related directly to the search engine's uniqueness.

When Google prepared to introduce its "what could be" superior search engine, its early organization knew it needed a crucial "how" hypothesis for "revenue streams" (the bottom-right box of the business model canvas). The result was to offer advertisers their own newly-conceived advertising value -- a way for advertisers to target their message and spending to particular customers. In Google's case, this "how" for revenue was related directly to the search engine's uniqueness.  Since a key part of the Khan Academy's purpose was to offer its library of learning videos for free to anyone anywhere, it too needed a hypothesis for revenue. Initially, it was a large donor (Bill Gates on behalf of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) that provided the "how" of revenue, as Bill Gates responded personally to the value of compelling purpose he found in the offering. As the Khan Academy took flight, the base of donors expanded, plus new types of "how" hypotheses for revenue included offering value to a range of partners: banks (for videos teaching about personal finance); testing organizations (for test prep videso) and more. Each revenue source was a type of customer, responding to value.

Since a key part of the Khan Academy's purpose was to offer its library of learning videos for free to anyone anywhere, it too needed a hypothesis for revenue. Initially, it was a large donor (Bill Gates on behalf of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) that provided the "how" of revenue, as Bill Gates responded personally to the value of compelling purpose he found in the offering. As the Khan Academy took flight, the base of donors expanded, plus new types of "how" hypotheses for revenue included offering value to a range of partners: banks (for videos teaching about personal finance); testing organizations (for test prep videso) and more. Each revenue source was a type of customer, responding to value.  For the founder of the Ocean Cleanup the "how" for catalyzing needed human resources for developing his prototype invention into a marketable offering featured a TED talk in which the founder conveyed his "what could be" hypothesis regarding a way to clean tiny plastic particles from oceans, including early results. Hundreds of professionals on multiple continents responded to the value of this purpose by volunteering their high-level skills and knowledge, on a part-time basis, for months if not years. As of 2016, a fully-developed offering was installed for its first paying customer of the government of Japan.

For the founder of the Ocean Cleanup the "how" for catalyzing needed human resources for developing his prototype invention into a marketable offering featured a TED talk in which the founder conveyed his "what could be" hypothesis regarding a way to clean tiny plastic particles from oceans, including early results. Hundreds of professionals on multiple continents responded to the value of this purpose by volunteering their high-level skills and knowledge, on a part-time basis, for months if not years. As of 2016, a fully-developed offering was installed for its first paying customer of the government of Japan.  Another non-profit, Teach For America (TFA), was built on the primary "how" hypothesis for the resource (on the left side of the canvas) of a high-caliber teaching corps of new college graduates by offering these graduates the value of purpose/meaning (a two-year experience of teaching in high-poverty schools). Founder Wendy Kopp recognized that her Princeton peers were taking jobs on Wall St. because "they couldn't think of anything better to do" and “We would jump at a chance to be part of something that brought thousands of our peers together to address the inequities in our country...” What's more, the value of this teacher resource to school districts meant that they agreed to hire TFA teachers directly, which provided a channel of distribution for TFA that absorbed the cost of their key resource and thereby reduced the need for revenue.

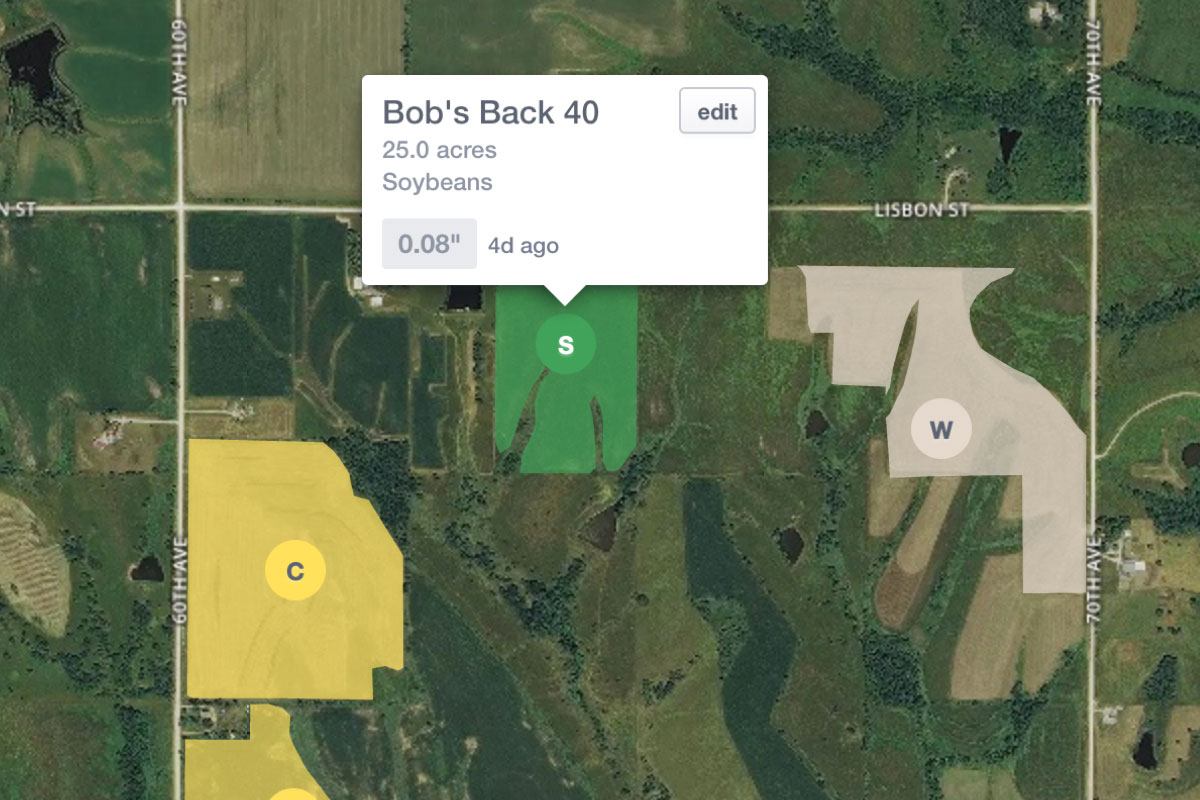

Another non-profit, Teach For America (TFA), was built on the primary "how" hypothesis for the resource (on the left side of the canvas) of a high-caliber teaching corps of new college graduates by offering these graduates the value of purpose/meaning (a two-year experience of teaching in high-poverty schools). Founder Wendy Kopp recognized that her Princeton peers were taking jobs on Wall St. because "they couldn't think of anything better to do" and “We would jump at a chance to be part of something that brought thousands of our peers together to address the inequities in our country...” What's more, the value of this teacher resource to school districts meant that they agreed to hire TFA teachers directly, which provided a channel of distribution for TFA that absorbed the cost of their key resource and thereby reduced the need for revenue.  FarmLogs began with a co-founder's deep personal knowledge of farming and farmers, based on growing up on a farm and on a family heritage of farming.

FarmLogs began with a co-founder's deep personal knowledge of farming and farmers, based on growing up on a farm and on a family heritage of farming.