LEARNING APPLICATIONS

Of Innovation's First Principles

"He taught me to look for the non-obvious ways to gain leverage times ten on an issue."

-- McKinsey & Company Manager about Bill Drayton

Quick Links:

Summary

A developed version of innovation's first principles is envisioned as faciliitating (or even enabling) an innovation learning system of the type that John W. Gardner associated with social renewal in 1964: a system "that would continuously reform itself in response to changing (social) 'ills' and would support the learner's continuous change and growth."[1]

- This type of learning system seems particularly fitting for the demands of present societal conditions, which call for converting innovation from skilled craft to methodology, with participation that is broad, intentional, and adaptive.

- It also appears particularly feasible at this time, especially if the articulation of innovation's organizing principles is feasible as a means for a system's grounding and connection. The feasibilty includes the prototype principles' indication that innovation's teaching and learning would fit as a natural element of evolution within existing systems of schooling.

- Moreover, themes that connect the wide array of resources available today reinforce a notion that Gardner expressed at least indirectly fifty years ago: Even as innovation's methodology may address "ills" on a societal level, for the learner and practitioner, the methodology amounts to quite a positive opportunity.

It is this integration of potential change catalysts -- personalized value as determined by learner "customers" alongside feasible levers for learning -- that seems to hold special promise for advancing human capability for innovation. Providing for this combination of catalysts is consistent with the prototype principles' "social differential."Sketches of four sample learning applications, based on the prototype principles, are situated within the type of innovation learning system that seems needed, feasible, and valuable.

A. An Innovation Learning System

The idea of grounding and connecting innovation's teaching and learning fits with calls, from at least the past 25 years, for systematic cultivation of capable practice of innovation and entrepreneurship. The voices of Peter Drucker and John W. Gardner were particularly strong.

Drucker argued throughout the late decades of the 20th century and into the 21st that a "post capitalist" society in which "knowledge is the only meaningful resource" means that: "Every organization … will have to learn how to innovate – and to learn that innovation can and should be organized as a systematic process." "What we need is an entrepreneurial society." Drucker noted separately that it's organizing principles that allow for converting any skilled craft to a methdology or discipline by making the craft broadly teachable.[2]

In the 1960s John W. Gardner framed the instructional challenge for social innovation in a way that remains pertinent 50 years later and for innovation overall, not social innovation alone. Gardner envisioned an innovation learning system that would continuously reform itself, including in response to changing "ills," and would support the learner's continuous change and growth:

The classic question of social reform has been: How can we cure this or that specifiable ill? Now, another question: How can we design a system that will continuously reform (i.e., renew) itself, beginning with the present specifiable (ills) … (to the) ills (we) cannot foresee?” “Like a scientist in a lab, part of enduring tradition/system, but …[2-1]

The alternative (to indoctrination) is to develop skills, attitudes, habits of mind and the kinds of knowledge and understanding that will be the instruments of continuous change and growth on the part of the young person. Then we will have fashioned a system.[2-2]

Changing Conditions --

In 2013, a ramped-up version of these same types of criteria for a system that cultivates innovation capability might be viewed within the context of "a new culture of learning," as advanced by Douglas Thomas and John Seely Brown -- a culture that cultivates the imagination for a world of constant change and where continuous learning is lifelong. Gardner's criteria are in keeping with the type of culture that Thomas and Seely Brown depict.[3]Similarly, the conditions of this present-day world can be viewed, as argued by historian David Christian, as an "innovation threshold" -- featuring conditions that simultaneously allow for and call for advancing complexity, based on human ability for collective learning and innovation. Indeed, one might say that the present threshold calls in particular for collective learning about innovation and its change dynamics. In founding and co-developing the "Big History Project," which includes curricula designed for the first two grades of high school, Christian has described his desire for today's youth to know the challenges and opportunities of this particular innovation threshold "moment."[3-2]

Overall, present societal conditions amplify the need for a robust, self-reforming innovation learning system. In fact, the conditions actually may signal that a new "social ill" is the need for such a system.

Feasibility & Value --

Fortunately, a learning system in keeping with the criteria that both Drucker and Gardner put forth seems more feasible at a time that it also seems more important than ever. Plus, for individual learners, the opportunities to develop capability with innovation's methodology is likely to represent quite a positive opportunity, rather than an ill.Considering these two aspects of a potential learning system -- feasibility and value -- together:

Feasibility --

First, feasibility of an innovation learning system seems connected fundamentally to feasibility of elaborating a set of innovation's enduring first principles. If the latter can be articulated, the result would indeed seem to provide for broad teachability and for a system to "continuously reform itself":

- Based on the prototype of first principles, fundamentals from two centuries ago have indeed endured. They have in fact supported the body of evolving knowledge. As of only a few years ago, it was typical for publications that introduced new ideas about innovation to make direct introductory reference to the foundational tenets provided by J.B. Say, Joseph Schumpeter, and Peter Drucker.

- Modern thought and action leaders, essentially, have drawn upon a foundation of implicit organizing principles as they have contributed to evolving understanding of innovation's dynamics within evolving societal conditions. This could be viewed as "renewal" that has already been occurring.

- Within the effective renewal, these leaders collectively have provided the themes that might be viewed explicitly as innovation's enduring fundamentals. It's the very chorus of explicative themes throughout recent resources that suggests that innovation's fundamentals can be harnessed for shared foundational understanding.

- Moreover, evolving understanding has included a body of richly differentiated resources that can be situated within the context of a shared framework of fundamentals. This site's mapping of innovation models, tools, and other resources to the prototype first principles (see Expanded Version and/or Quick Reference) illustrates the gist of the way that principles seem to provide a natural means for leveraging resources within an innovation learning system.

Value --

Second, based on the prototype set of first principles, the very "skills, attitudes, habits of mind ..." that are fundamental to innovation's methodology would seem to be those that can serve as "instruments of continous change and growth" on the part of individual practitioners:

- That's because expert resources indicate thematically that the methodology calls for a personalized combination of high-level abilities, pertinent knowledge, and the driving energy of intrinsic motivation.

- As described just below, that formula may be as potent as it is needed. And a developed set of innovation's first principles can be viewed as setting the agenda for learning that can support such personalized combinations.

Learning Agenda Framed by Fundamentals --

Innovation's first principles can be viewed as establishing an essential agenda for what is to be learned within an innovation learning system, where the ultimate learning is a personalized connection to a methodology that calls for generally high-level abilities and pertinent knowledge.The explicit framework of innovation's first principles shines light on the way that this ultimate scenario of learning could be scaffolded gradually and intentionally. For example, considering the prototype first principles:

Principles #1 & #2 --

The first two prototype principles emphasize the societal stage, or marketplace (including the social and public "marketplaces") in which change plays out: What is innovation, why does it matter, and how does it work?

Given effective articulation of innovation's enduring fundamentals, virtually anyone can apprehend the nature of innovation's change dynamics. This includes understanding the nature of innovation's distinctive purpose and means of creative expression vis-a-vis the related purposes and means of science and invention. For example:

- We all participate in the marketplace of change and resource leverage as customers, or not. For example, we may or may not participate in recycling. The articulation of fundamentals can shine light on how and why an accumulation of positive individual "customer" response to offerings determines the effect of resource leverage within myriad contexts.

- Plenty of concrete examples associated with the same fundamentals can allow for seeing innovation's driving constants vis-a-vis it many variations:

- This includes seeing innovation's methodology as one that is based on particular types of hypotheses, which depend upon integrating and applying knowledge from virtually any field or discipline. This includes seeing the way that innovation's hypotheses relate to, and sometimes draw upon, advances in science and invention.

- It also includes seeing that innovation's hypotheses are developed and deployed by those in widely-varying specialized roles throughout the commercial, social, and public sectors of a global economy.

Principles #3 & #4 --

The second two prototype principles emphasize the driving role of innovation practitioners: How are effective innovation hypotheses developed and deployed, and why would practitioners engage the challenges of creating change-catalyzing value for others?

- For the innovation hypotheses that connect knowledge that is widely known or knowable (e.g., the hypothesis that dogs can be trained to aid blind persons), examples can support understanding the nature of a practitioner's new connection of knowledge that is geared to innovation's direct purpose of making more fruitful use of existing resources. Structures for plentiful examples can make the nature of the hypotheses familiar.

- Further, the stories behind real-world examples can highlight practitioners' connection of personal value to societal purpose. For innovation's methodology, the exploration of intrinsic motivators is built into the fundamentals to be learned. The fundamental principles shine light on the way that the methodology calls for applying/expressing personal strengths toward interests that are personal but also extend beyond oneself.

For humans in general, this value of "engagement" (of personal strengths) and "meaning" (connecting to purpose outside of oneself) is associated with "uncoerced choice." It's associated with experiences worth doing for the sake of this value alone.[3-3]

Establishing this type of stage for learning -- essentially beginning with "do re mi" -- allows for explication, examples, and a trajectory of structured opportunities for hands-on exploration and practice. It can demystify innovation's creative purpose and expression, as a seeming lever for relating that purpose and practice to individual strengths and interests. In fact, the hands-on exploration can support individual learners in finding their strengths and interests.For learners, this combination -- understanding the fundamentals of innovation's purpose and practice, plus finding immediate personalized value within early and continued experiences of hands-on practice -- seems important. That's because the trajectory of associated knowledge and abilities is ambitious, as discussed just below.

Challenge Interwoven with Compelling Personal Value --

Perhaps the overall theme of a strand of expert work on creativity is that ambitious demands coexist with the methodology's call for intrinsic motivators (in particular, the motivators of "engagement" and "meaning").This strand of expert resources features insight regarding the nature of the "skills, attitudes, habits of mind ..." associated with innovation's methodology. It includes a body of research on "creativity" during the second half of the 20th century, which represented at that time an unprecedented amount of federally funded social science research. Today, this body of work is complemented and supplemented by continual insights from the specialized fields of neuroscience, cognitive science, learning science, education, and more.

I've drawn upon one particular model as a framework for considering innovation methodology's interweaving of demands and value:

WICS Framework

Robert Sternberg's WICS model (Wisdom, Intelligence, and Creativity Synthesized) "unpacks" the creative function that is shared by science, invention, and innovation.[4] This unpacking sets the stage for elaborating the way that innovation's direct purpose and medium of expression differs from, but also relates to, the direct purpose and media of expression of science and invention.The model elaborates creativity's ambitiousness in both breadth and level of abilities, and also speaks to its motivational element. Based on decades of scholarship, Sternberg's elaboration, which the model presents in reverse order of the WICS acronym, clarifies the high demand on abilities for producing any type of creativity:

- "Creativity": "(W)ork that is novel (original, unexpected), high in quality, and appropriate (useful, meets task constraints)."

"Creavity is the potential to produce and implement ideas that are novel and high in quality. (Creativity) goes beyond the creative intelligence ... in that it contains attitudinal, motivational, personality, and environmental components as well as the cognitive one of creative intelligence."

- Intelligence: "Creative work and the broad-based creativity underlying it, requires applying and balancing the three intellectual abilities -- creative, analytical, and practical -- all of which can be developed."

"Creative ability is used to generate ideas. ... Without well-developed analytical ability, the creative thinker is as likely to pursue bad ideas as to pursue good ones ... Practical ability is used to translate theory into practice and abstract ideas into practical accomplishments. It is also used to convince other people that an idea is valuable ... (and) to recognize ideas that have a potential audience."

- "Analytical ability involves analyzing, evaluating, judging, inferring, critiquing, and comparing and contrasting."

- "Creative ability involves creating, designing, inventing, imagining, supposing, and exploring."

- "Practical ability involves applying, using, implementing, contextualizing, and putting into practice."

- Wisdom: "People can be intelligent and even creative but also foolish."

"(W)isdom is the application of intelligence, creativity, and knowledge as mediated by positive ethical values toward the achievement of a common good through a balance among (a) intrapersonal, (b) interpersonal, and (c) extrapersonal interests over the short and long term."

Such abilities for applying knowledge usefully are only as effective as the pertinent knowledge that they have to work with. Moreover, separate work in the field of cognitive science argues that the cognitive abilities are developed by way of assimilating knowledge, such as the body of knowledge represented in the U.S. by the K-12 Common Core State Standards.

Using the same WICS core components further as a framework, complementary perspective from additional expert resources: (i) reinforces the challenges of these abilities, including the challenge of finding personal intrinsic motivators; and (ii) speaks to the way that an innovation learning system would seem to support the overall challenges:

Creativity --

For the attitudinal, motivational, and personality aspects of this WICS component, Sir Ken Robinson has described that individuals' strengths-interests intersection can be "buried deep."[4-2] In the U.S. it seems safe to say that the status quo has been that of intrinsic motivators being elusive for perhaps the vast majority of learners, especially in terms of relating strengths and interests to schooling and work.This includes the population of high academic achievers. As one example, in A New Culture of Learning, one of the authors described that, for his UCLA students, coming up with a personal passion was the greatest challenge in preparing for capstone thesis projects.

Similarly, Wendy Kopp drew upon her understanding of this valued-but-elusive intersection with regard to her intellectually high-achieving peers. In founding Teach for America, Kopp hypothesized that many of her peers would be interested in serving in a teaching corps, as they were otherwise entering fields of work in which they had little interest because "they couldn't think of anything else to do."[4-3]

For innovation's lead change agents in particular, recent work by Tony Wagner has reinforced the factor of intrinsic motivation within trajectories of developing overall innovation capability. Wagner has hypothesized that finding intrinsic motivators can support access to what he has called seven "survival skills" associated with the 21st century, which includes the combination of intellectual and creative abilities.[4-4]

Effective learning tools for scaffolding innovation's practice, almost by definition, would serve simultaneously as a new type of structure for exploring personal interests and motivators. This feature of the methodology -- its call for personalization -- represents an interesting opportunity for individuals that is associated with a pressing societal need.

Intelligence --

Cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham argues that the very difficulty of learning the intellectual abilities that Sternberg associates with creativity is the reason that students "don't like school": ~"We're naturally curious but not naturally good thinkers." Willingham argues that the difficulty is the reason that schooling calls for skillful instructional conditions, allowing for students' "successful thinking." [4-1]But Willingham holds too that "meaning" supports successful thinking.[4-5] And it is in this way that innovation methodology's call for personal strengths and interests, especially when connected to societal needs, can provide seeming support for cognitive demands. Again, "well being" theory holds that both "engagement" (of strengths and interests) and "meaning" represent "uncoerced choice," or value for its own sake. [4-7]

Wisdom --

Finally, the challenge associated with developing what Nobel prize recipient Daniel Kahneman has called "responsible creativity" is especially important for an innovation learning system in light of the moral neutrality of innovation's driving fundamentals.The global "innovation threshold" depicted by Christian calls for channeling creative expression toward what the WICS model describes as "the achievement of a common good through a balance among (a) intrapersonal, (b) interpersonal, and (c) extrapersonal interests over the short and long term."

And this WICS element, too, is not obviously accessed among would-be innovators. It calls for instruction. In the 1960s, Gardner noted:

"(W)e must help the individual to re-establish a meaningful relationship with a larger context of purpose. … (O)ne of the reasons young people do not commit themselves to the larger social enterprise is that they are genuinely baffled as to the nature of that enterprise. … They do not see where they fit in. If they are to commit themselves to the best in their own society, it is not exhortation they need but instruction. … We must also help the individual to discover how such commitments may be made without surrendering individuality."[4-6]

For this element, too, it seems that effective curricula and tools for understanding innovation's fundamentals (e.g., why innovation matters) would, or could, serve simultaneously as tools that support individuals in connecting interests and strengths to a larger context of purpose.

Harnessing Both Resources & Intrinsic Motivators --

Feasible and valuable does not mean easy. A societal advance in innovation capability (more yield from human resources) involves challenges of learning trajectories. With this, the greatest promise of an innovation learning system may boil down to its provision for illuminating to individual learners the compelling personalized value that innovation's methodology can represent, at the same time that it scaffolds capability.In other words, an innovation learning system would seem to provide for learning about the methodology's personalized value in addition to its practice. In this sense, an innovation learning system can be viewed as a potentially synergistic "offering" to student "customers." It would represent an example of "customer capital's" grounding in teaching and learning:

"If only I knew what you wanted, I could sell more to you.

If only you knew what I could do for you, you would buy more from me."

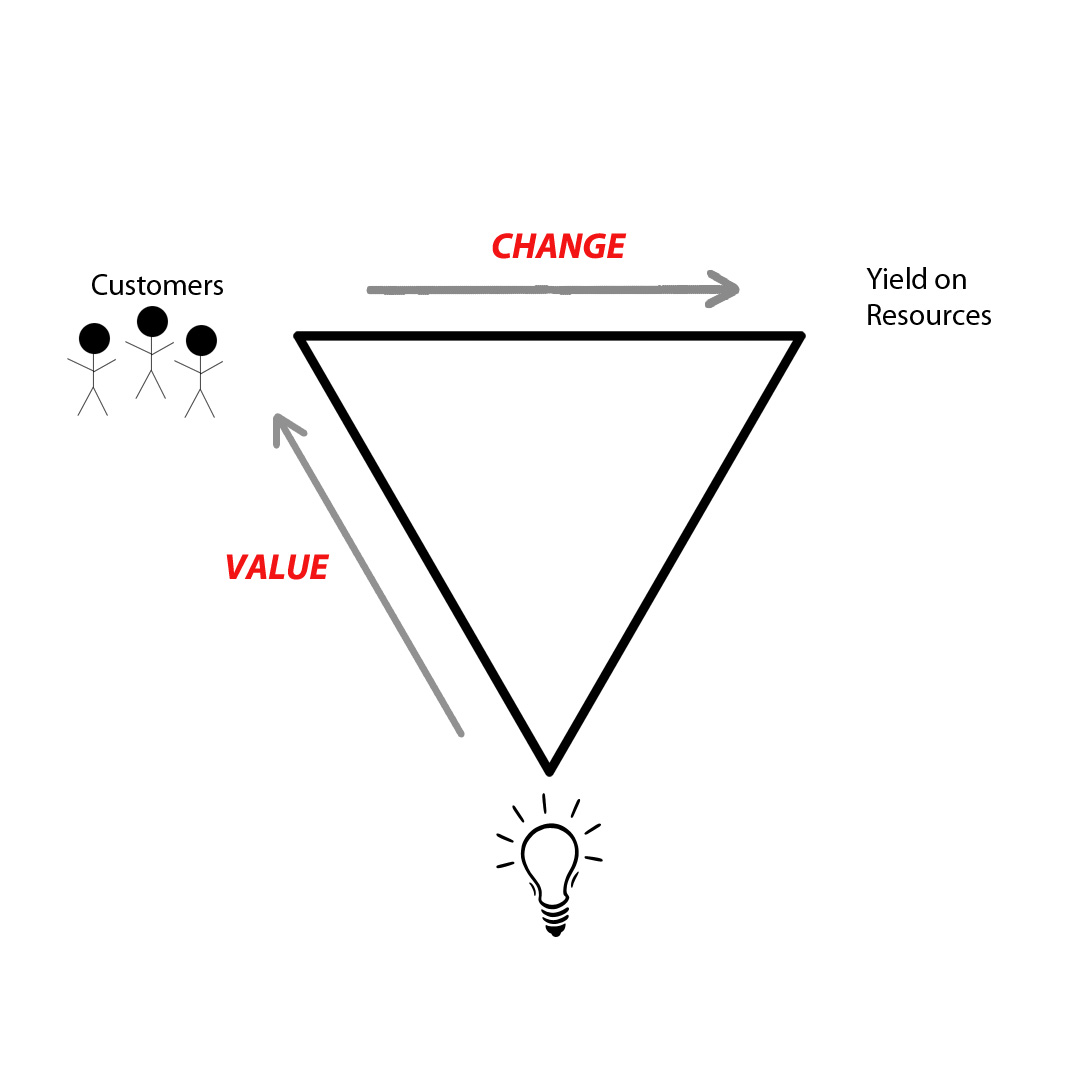

No matter the approach to the societal need for innovation capability, the end fits with many examples of social innovation in that it requires the dual change catalysts of value and learning. Learners are simultaneously the "customers" and the (human) "resources" that become more fruitful:

B. Using an Innovation Learning System

Each of this site's learning application sketches aims to support two overarching goals:

- foster intelligibility of innovation -- what is it, why does it matter (to society and to me), and how does it work;

- foster capability for producing innovation, as direct, hands-on agents.

The blend of intelligibility and hands-on practice fits with guidelines from learning science for development of both skills and confidence, such as the following:

- Convey clearly what the learner is to do ("unpack it").

- Demonstrate what the learner is to do.

- Engage partially completed examples of the work with learners.

- Allow for plentiful practice. [5]

Each of the two overarching goals is addressed very briefly just below and then considered vis-a-vis Thomas and Seely Brown's broader framework for "a new culture of learning."

See more.

1. Foster intelligibility of innovation

Intelligibility is to inform and inspire. As Csikszentmihalyi and colleagues have noted:

"Humans can observe and/or be shown how activities of humans have changed the environment, fostering realization that other people may be able to also bring about change ... A sense of what has been done helps lead to a sense of what might be done as well as an appreciation for the kinds of established constraints that might affect imagined changes."[5-1]

Intelligibility includes relating innovation's direct purpose and methods to the same for science and invention, as directly related complements. It also includes elaborating the varying modes of engaging innovation's methodology. This variation in engagement includes fundamentals such as:

- contributing overarching hypotheses of "what could be" as new value versus contributing to "how it could become" hypotheses within many different types of specialized roles (from engineering to marketing)

- differing pathways to innovation's direct purpose -- for example, one might begin with science and/or invention and proceed to innovation's translation of these advances, or one might begin with direct reference to the marketplace, etc.

- different innovation "personas," such as those elaborated by IDEO's Tom Kelley, which overlaps somewhat with the preceding types of variation, but delineates a generally different dimension of variation and overall perspective. [10-1]

Intelligibility of innovation and its methodology is envisioned as a trajectory, with an initial access point for apprehending innovation and its practice supported by skillful unpacking and followed by experience-based opportunities for deepening understanding. Bruner referred to a "style of thought" that distinguishes any discipline and that requires time and participation for absorption.

The lens of first principles is intended to help launch and support a trajectory of intelligibility by providing continued grounding and connection. For example, first principles can serve as a home base for the many dimensions of variation on the same thematic fundamentals:

Based on the prototype principles, constants would feature:

- the hypotheses for "what could be" as new value and "how it could become an offering accessible to customers and a catalyst of change";

- the existing knowledge that was connected to form each hypothesis (i.e., the evaluative-generative processing of the knowledge); and

- the offering's targets of change (adoption, behavior, capability).

As but a few examples of variables:

- The practitioner's original point(s) of reference. For example:

- starting with new technical capability or new knowledge;

- starting with observation of the production system (including "discovery" linked to customers or the marketplace);

- starting with a goal (e.g., strategy or brief).

- The type of technology and its centrality to the offering (e.g., new technology versus "appropriate" technology versus new application of existing technology versus no central technology role).

- The level and types of knowledge connected.

- How a lever-based vision (overarching hypothesis) came about (its story), including the practitioner/s' version of creative processing and relevant internal and external conditions.

- Organizational context (size and type, including established organization versus start-up, etc.).

- Classification of leverage and scale (e.g., "disruptive," transformational, other), which could begin with an established classification system (e.g., by Jeff DeGraff and Shawn Quinn).

Intelligibility also can help distinguish examples of excellence. The Kauffman Foundation’s Panel on Entrepreneurship Curriculum in Higher Education described an analogy with music:

Departments of music composition cannot make students creative. But studying how great music is made can ignite whatever creativity students possess and help bring it to expression. The aim of studying composition is to unpack works of genius and excellence and thereby lead students beyond imitation to originality. … Making innovation intelligible may help students to imagine and engage in entrepreneurial activities they otherwise might not have considered.[5-2]

At this web site, the cases of social innovation viewed through the lens of the prototype first principles are intended to help convey the type of unpacking that first principles can support.

Additional focused support for intelligibility comes from this site's sketches for online video lecture(s) and an interactive online databank of innovation profiles.

2. Foster capability for producing innovation

As with intelligibility, the grounding and connection provided by first principles is intended to help launch and support a trajectory of capability, especially for students drawn to innovation's direct purpose and medium of expression. In particular, first principles are to support navigation and productive practice with the concepts, including support for using resources such as innovation models and tools.

With a developed version of first principles situating widely-varying models and tools, there is guidance for selection and use of these resources, including guidance for experimenting with varying personal approaches to the methodology. For example:

Tools geared to early practice could support practitioners' development toward mastery's "deep-structure" knowledge, including spontaneous, day-to-day skill at generating and acting on effective hypotheses for resource leverage. This is akin to the message within a cookbook's introduction from Julia Child and colleagues:

"Our primary purpose in this book is to teach you how to cook, so that you will understand fundamental techniques and gradually be able to divorce yourself from a dependence on recipes." [6-4]

Other models and tools benefit from the complement of developed fundamentals (e.g., "disruptive" innovation requires a customer value proposition that is as robust fundamentally as it is fitting to the model). In these cases, it may be skilled cooks, not beginners, who can make the best use of a recipe.

(Again, see sample mapping of a set of models and tools here based on the prototype principles.)

Further, themes that span resources point to overall considerations like the following for cultivating innovation's practice, including by way of models and tools:

i. Begin with a subject area of change that the learner knows deeply and cares about advancing.

It is difficult to convince someone to care deeply about advancing a transaction-based subject that they do not already care about. But if the practitioner’s intrinsic interest is in place, this supports focus on practice with innovation's direct purpose of leverage and its hypotheses. Intrinsic interest supports practice with the methodology's fundamental stance of "inner-direction and other-focus."

IDEO's General Manager, Tom Kelley, advised:

"(T)his work [of understanding customers] requires curiosity. How can you get better at it? Find a field that commands your interest." [6]

Further, certain models and tools are likely to prompt the practitioner to consider all pertinent strands of knowledge for innovation hypotheses, thereby adding to an existing base of subject knowledge and understanding the reason for doing so.

ii. Personalize habits & practices, including allowing for focus on innovation's "how" hypotheses.

With the benefit of constant reference to innovation's first principles, encourage experimentation with innovation's variations of practice.

In addition to the types of variation described under Intelligibility above, varying methodological practices include practices such as those highlighted in Where Good Ideas Come From, The Natural History of Innovation (e.g., keeping a log of observations). This type of resource could help learners understand variations in aids for thinking/processing/incubation, plus the way that such aids are shared with invention and science. [10-2]

Other models and tools could support hands-on aspects of practice such as: co-creation of ideas with customers; specially directed observation of customers; testing hypotheses; the design of offerings and business models; etc.

The grounding of a strong set of first principles could promote flexibility, experimentation, and reflection, without chaos.

Within personalization, allow for focus on generating strong "how" hypotheses. This contribution is valuable and may be especially motivating to some individuals.

iii. Begin with emphasis on leverage over scale, as a foundation for developing and supporting big ideas.

The best initial practice topics -- in addition to being personally meaningful -- may be small in scale and/or difficulty of change.

First, this could allow for experiencing the type of value that innovation's skilled-craft practitioners derive from the practice as a complement to creating value for customers. This includes beginning to understand the conviction associated with effective ideas, described for example as:

"Effective surprise" -- "Good observations often seem simple in retrospect, but the truth is that it takes a certain discipline to step back from your routine and look at things with a fresh eye."[7]

And as the "design attitude" that it is difficult to (conceive of) an outstanding alternative, but once you have, the decision (to choose it) ... becomes trivial."[8] It's to support direct experience with, as Wendy Kopp put it regarding a national teacher corps, “How could this not already be in place?” Or as A. G. Lafley and Ram Charan put it, the experience of generating and acting on breakthrough ideas helps develop "a certain unclassifiable sixth sense of what is possible." [9]

Ideally, learners could sample the experience of conviction both individually and within teams.

Second, small scale also could support practice with acting on a compelling idea -- cultivating practical abilities -- while containing the demands of implementation within learning contexts.

Acting on ideas in one way or another allows for the possibility of learning from failing, especially if learners recognize ways they did not observe fundamentals and especially if the failure motivates them to adjust and try again. Drucker held that:

Entrepreneurship is “risky“ mainly because so few of the so-called entrepreneurs know what they are doing. They lack the methodology. They violate elementary and well-known rules.[11]

Innovators … improve with practice. But only if they practice the right method.[12]

3. Align with "a new culture of learning"

A grounded and connected learning system for innovation, associated with a developed version of first principles, seems fundamentally compatible with a world of constant change and associated new culture of learning depicted by Thomas and Seely Brown. In fact, it seems that practice with innovation's methodology would serve as direct practice ground for the authors' projected new culture of learning.

Again, Thomas and Seely Brown describe the new culture of learning as the effective fusion of two core elements:

i. The massive information network that provides almost unlimited access and resources to learn about anything (and is constantly changing).

ii. A bounded and structured environment that allows for unlimited agency to build and experiment with things within those boundaries.

The authors note that the challenge to traditional approaches to learning is "to find a way to marry structure with the freedom to create something altogether new." The prototype version of innovation's first principles not only calls for exactly this marriage of elements, it notes the fundamental fit of practitioner passion, which is similarly fundamental to Thomas and Seely Brown's framework:

"Students learn best when they are able to follow their passion and operate within the constraints of a bounded environment."

"The passion of the learner is the greatest source of inspiration but also the largest reservoir of tacit knowledge," and "(tacit understanding) relates most deeply to the associations and connections among various pieces of knowledge."

In the new culture of learning, change is not only embraced, it's created. The new culture is about "how the imagination is cultivated to harness the power of almost unlimited resources to create something personally meaningful." Practice within the context of innovation's boundaries could support harnessing this same power when it is linked also to value as determined by others.

Within the new culture of learning, the design for learning is built upon:

- Knowing -- which is "increasingly about knowing how to find and evaluate information on any given topic"

- Making -- which features hands-on learning and "requires deep and practical knowledge of the thing one is trying to create"

- Playing -- which involves: (i) the "ability to organize, connect, and make sense of things"; (ii) the organizing principle of a "leap" ... over the gap between the knowledge one is given and a desired end result; and (iii) a questing disposition.

Good questions are especially important, and peer-to-peer learning is integral, based on active engagement with shared interests and opportunities.

Overall, ideas throughout Thomas and Seely Brown's framework speak to mutual benefit and reinforcement between innovation's fundamentals and a new culture of learning. For example:

- The new culture provides guidance for peer-to-peer learning (among collectives determined by shared interests), which could support hands-on practice with innovation's methods and purpose.

- In cultivating innovation learning among young students, ideas in Thomas and Seely Brown's framework suggest that it could make sense to begin simply with students asking questions "about things that really matter to them." Then in alignment with the innovation model of design thinking, there could be movement toward the same type of questions bound by design thinking's mantra of "How might we ...?"

C. Sketches of Learning Applications

The four sketches below draw upon the prototype of innovation's first principles (and also principles of teaching and learning) in order to illustrate potential dynamics of an overall self-reforming innovation learning system.

Each sketch is geared to the overarching goals of innovation intelligibility and capability:

1. Elegant Online Video Lecture(s)

An introductory set of ~10-minute videos would be based on elegant articulation and depiction of an elegantly developed set of first principles.

Like the Khan Academy's Introduction to Algebra:

- The idea would be to establish innovation's essential "what, why, and how."

- The innovation introduction might begin very briefly with the work of J.B. Say (rather than Galileo), perhaps by linking words written by Say with words that have been expressed by someone like Steve Jobs.

- The content would be clear enough to be accessible to everyone, including youth.

The seeming ideal online location for the video lecture would be within the Khan Academy's online collection. This has the clear benefit of accessibility; however, equally important, the notion of innovation's first principles and of the effect of an innovation learning system seem to represent a strong fit with Salman Khan's philosophy of learning, as described in The One World Schoolhouse and discussed within public interviews.

For example:

- For each individual learner, the grounding intended by a high-quality set of first principles is in keeping with the "associative" learning that Salman Khan espoused in The One World Schoolhouse (and as reinforced by cognitive science and other fundamental principles of learning). To begin, clear principles are to serve as a bridge from what learners already know to the new concepts. Clear core concepts are to elucidate a crucial lens for a new way of seeing what learners already know. Plus, the high-quality video lectures provide for re-visiting the concepts as often as desired.

- A video lecture also fits with the idea of consolidating learning by facilitating practice, as with a "flipped" classroom, where in-person time with teachers focuses on using the concepts (although the video could be used both as homework and within classrooms). A video lecture fits too with not expecting tens of thousands of indivi dual instructors to construct and present a lecture -- in this case on a topic that most would not have have the prior opportunity to learn in a structured way. Many teachers will be learning alongside students, which seems fitting for a century in which learning is anticipated as lifelong.

- Free and visible online access is to promote "equal" access (or close to equal and getting closer) to a high-quality lecture(s) about innovation's practice.

- To quote Khan from a television interview: ~"America is this hotbead of innovation, but it's a very small sliver that's participating in it ... (The Khan Academy's ideas ultimately are) about 'How can we get more kids (everywhere) who can create things -- who can be more creative?' This is what's it all about." [11-1]

- The notion of an innovation learning system, built on a strong foundation of fundamentals, is based on this same idea. Ideally, it's to help nurture "a sense of wonder" (a core Khan Academy value) about what is possible.

2. Searchable, Interactive Online Databank

"Human beings can observe and/or be shown how the activities of humanity have changed the environment, fostering the realization that other people may be able to also bring about change. ... A sense of what has been done helps lead to a sense of what might be done, as well as an appreciation for the kinds of established constraints that might affect imagined changes." [12-1]

A databank is to support an online "gallery" of offerings, providing plentiful and varying examples in such a way that it aids intelligibility of innovation's constants and variables:

- To begin, each offering "portrait" features its core value proposition -- a marketplace view. The gallery is fundamentally about portraits of "value" (change-catalyzing value).

- Plus, visitors can look behind the scenes of any offering, to a template-based view of the innovator's methods:

- The template is based on innovation's constants (the key hypotheses, the knowledge connected, and the offering's goals for change).

- With tags highlighting the many variables associated with the constants.

These two vantage points -- a marketplace view and a practitioner's view -- are to aid visitors in both browsing and interacting (e.g., searching, grouping, etc.). Overall, the aim is support the view of every innovation example as but a variant on themes of fundamentals. From cognitive science:"The surest way to help students understand an abstraction is to expose them to many different versions of the abstraction."[12-3]

An Ongoing World's Fair of Innovation --

The ideal experience of visiting an eventual online gallery of offering profiles might be like visiting a hands-on world's fair or museum or trade-show:Wings and special exhibits could be curator-determined, but also interactive, such that visitors could customize, archive, tag, and share their own collections. Visitors also could receive notices of (or search for) new profiles.

A wing's cluster of profiles might reflect any combination of constants and variables. For example, curated wings might feature profiles of offerings that are:

- "world changing";

- based on new technology;

- based on "appropriate technology";

- based on ordinary knowledge;

- illuminating of the "social differential," including catalysts for change in customers' behavior and capability;

- growing out of startup organizations versus other types of organizations;

- contributing to sustainable development;

- within ventures seeking a "triple bottom line";

- based on "seizing opportunity" versus "addressing a problem";

- illustrating increasing complexity, from an effective new connection of simple knowledge to a connection of a complex web of knowledge;

- and so on.

Since visitors could go from one wing to another within a second or two, rather than walking long distances, there could be a large number of wings. Also, a visitor could arrange a wing's profiles according to personal preferences and could create, save, and share their own wings.

See more.The possibilities for clustering are limited only tags. In addition to variables such as those above, tags might highlight offerings that are:

- co-created with customers;

- based on public-private partnerships;

- benefiting a certain category of customer (retirees, teens, women, children, etc.)

- originally conceived of as new utility with subsequent need to figure out a successful means of revenue;

- enacted within public service agencies;

- featuring "disruptive" innovation for any sector;

- featuring successful "sustainable" innovation for any sector;

- enacted by youth;

- catalyzing change in customers' behavior or capability, arranged by difficulty of change and learning;

- led by a woman;

- featuring a like-business-model (e.g., matchmaking of any type);

- filling a gap in the marketplace;

- and so on.

The fair (or museum or trade show) also could offer learning tools beyond its collection of profiles. It could include resources for educators (e.g., practice topics for youth), links to related resources such as "Open IDEO," and much more.

Subscribe to "Offering of the Day" --

The database could deliver an "offering of the day (or week)" delivered via email or social media (and perhaps featured independently in news media as "good news"). Subscribers could opt for particular industries for their offering of the day, with everyone receiving one universal selection. The latter is to support intelligibility of innovation's constants across industries and more, including supporting cross-pollination.

Essentially, an offering of the day is to put innovation's concrete purpose and practice into public drinking water, to stimulate conversations and questions. The offerings should be clear enough for middle school students.

Sample Profiles --

To demonstrate the idea, based on a provisional template associated with the prototype principles, see sample profiles of three actual offerings. (Warning: The examples are in need of update in terms of both substance and form. Hopefully, the gist of the value will be evident.)

How this might become --

The practitioner vantage point is fundamental to robust intelligibility of innovation hypotheses and other core elements of methodology. Indeed, the database represents an opportunity for private-public partnership. It's an opportunity for practitioners of many types to provide their intellectual support of the societal good of education, including the K-12 level.Feasibility of accessing the practitioner vantage point would likely need to draw upon pilot testing. As one way to start, a bank of exploratory profiles could be based on interviewing up to hundreds of practitioners with successful offerings. And this would not even need to be primary research. For example, research that served as the basis for findings within The Innovator's DNA included a similar goal regarding "when and how" entrepreneurs "came up with ideas that launched new businesses or products." If the authors were inclined, this research could be used further to test the idea of an online databank and template-based profiles. If other scholars and organizations possess similar primary research, a combination of data sources could provide for suitable representation of innovation's spectrum of classification.

Whether "intelligence" for the profiles is primary or secondary (but valid), results of this type of experimentation -- incorporating widely varying examples -- might contribute to development or testing of the hypothesis for valid first principles.

Curation is in part to ensure that profiles achieve the goal of distinguishing constants from variables, including supporting strong use of tags. It's also to support visitor experiences. However, the end is more important that the means, and curation may not be the best approach, other than perhaps to establish a starting point of a critical mass of examples.

Benefits --

Even well short of the ideal, the intended benefits of a searchable, template-based databank are to:

- aid intelligibility (seeing innovation as but variations on a small set of themes);

- inspire;

- spread knowledge of successful offerings (especially of the often local or regional examples of social innovation, which can be "borrowed").

Overall, a databank would aim to establish structural capital -- that is, "to organize and distribute strategically collected data for

- rapid knowledge sharing

- collective knowledge growth

- shortened lead times

- more productive people."

3. For Youth -- Becoming Innovation Natives"The greatest challenge for adults in nurturing children's creativity is to help children find and develop their Creativity Intersection -- the area where their talents, skills, and interests overlap."[21-1]

The prototype principles help reveal the feasibility of engagement with innovation's practice as of a relatively early age, since the methodology does not require sophisticated knowledge. It only requires deep and "pertinent" knowledge of a transactions-based subject, along with thinking skills, and value for advancing the subject's productivity.In fact, Peter Drucker noted that innovation's function and practice "pertains to all activities of human beings other than those one might term 'existential' rather than 'social.'" This allows for a vast practice ground, including causes pertinent as early as middle school years (e.g, school bullying, environmental causes of widely varying types, community service). Youth possess power as a moral voice and are technologically facile. Their early experiences of learning how to catalyze change could produce meaningful results.

Should we? --

For the U.S., one key question is "Should we?" Given a public education system already seriously stretched, especially with 45 states focused on implementing Common Core State Standards ("common core"), adding "one more thing" seems unrealistic and potentially unwise.In this case, however, it's conceivable that more is less, based on strategic inclusion of innovation instruction within the broad two-part strategy expressed by the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO):

- providing a base of what "every" student needs to know (supported by the common core)

- providing for personalized experiences of that base for "each" student.

For example:In terms of what "every" student should know, introductory units about innovation's fundamentals would fit naturally within existing Social Studies curricula, beginning with middle school years. Innovation is afterall about societal use of resources and about change by way of "value." Its practice and effects are rooted in human and social dynamics. In the 21st century, every student should know what innovation is, why it matters (to society and potentially to each individual), and how it works.

Plus, with respect to the second part of the CCSSO strategy, innovation's practice by its nature calls for personalized engagement. To begin, it calls for a connection between value to a practitioner and value to "customers." Ideally, this connection extends as value to society as well. Practice with innovation's methodology fits well with guidelines for personalizing that were produced by a U.S. summit (which included CCSSO participation). It provides an instrument for personalizing the base of what every student should know.

What might strategic inclusion look like?

Again, with regard to what "every" student needs to know, there are places within standard curricula (e.g., Social Studies) that provide a seeming strategic spot to incorporate intelligibility about what innovation is, why it matters, and how it works.Standard inclusion might begin with a series of pre-designed, digitally-supported introductory units. Design of units could draw upon resources such as:

- a high-quality version of innovation's first principles

- principles of teaching and learning

- guidelines for personalizing learning

- the treasure trove of existing resources about innovation and about creativity more broadly

- newly created resources such as video lectures tailored to youth and a searchable and interactive database of template-based innovation profiles.

Classroom use of pre-designed units might benefit further from a developed version of innovation's first principles. For example, given a searchable database of template-based innovation profiles, personalization might begin by assigning students to:

- search for a set of offering profiles that address a cause of personal interest

- plus choose a favorite, and explain why

- choose the way s/he would most like to support and/or modify such an endeavor

- describe the way that seemingly differing offerings share constant fundamentals

- comment on the types of knowledge that an offering applies

- for an offering that draws upon advances in science and/or invention, contrast the offering's innovation hypotheses with the hypotheses for science and invention

- create a cluster of offerings that reflect a personal basis for interest

- and much more.

An interactive database offers many assignment possibilities in support of innovation intelligibility and also in support of exploring one's interests and strengths (intrinsic motivators).For at least a minimal introduction, this type of exposure could begin no later than 7th or 8th grade, and continue through high school. The combination of high-quality principles and associated instructional instruments could support teachers' continuing learning alongside students. It seems fitting that innovation's instruction would model for students a new epoch's call for continuous learning.

Beyond Intelligibility, Cultivating Capability --

Eventually, students could practice developing and testing innovation hypotheses and much more. Most important, all assignments should emphasize what each student finds important, compelling, interesting -- intrinsically motivating.Students should understand that intrinsic motivation is fundamental to innovation's methodology. A developed version of innovation's first principles would provide for explicating this and other unifying concepts throughout a student's experiences over time and place, facilitating deepening understanding.

Pre-designed units could become more open-ended, continuing to draw upon a wealth of existing resources such as:

- Guidelines for teaching "creativity" to youth (e.g, Theresa Amabile's guidelines in Growing Up Creative), customized to innovation's purpose.

- Questions such as those from A New Culture of Learning ... "What really matters? What do I really care about?" Link these types of questions (getting at passions) to innovation practices such as observing, questioning, and listening.

More open-ended tasks associated within these units would allow students to gain hands-on experience with innovation's methods along with deepening understanding. For example:

- Generate and test innovation hypotheses about self-selected causes of interest, including both "what" and "how" hypotheses and within ~cross-functional teams. Compare the nature of these hypotheses to those for science and invention.

- Practice developing innovation hypotheses that build upon advances in science and invention.

- Draw upon innovation case studies prepared especially for youth. Highlight the way that the practice of creating innovation’s purposeful change, whether directly or indirectly, calls upon a cross-section of individual strengths, channeled to a shared passion.

- Use innovation models and tools customized for youth and/or their teachers as "recipes" for developing and acting on hypotheses. Let emerging compelling ideas serve as catalysts for design and action (which might extend outside of the school day).

- Within implemented offerings, include student reflection on preferred roles (getting at the intrinsic motivators of signature strengths and preferences). Like a theatrical production, with roles that extend well beyond lead actors (to lighting, music, stage sets, costumes, marketing, etc.), the roles involved in producing change-catalyzing value tend to be many and varied. There is enough value in a compelling idea to extend to many "practitioners."

Overall, innovation instruction can emphasize the way that innovation's direct purpose, hypotheses, and medium of expression relate to the same for science and invention. Students can be encouraged to think about personal preferences among these complementary methodologies, including over time. (This is a career planning aid and youth development aid.)As understanding takes hold among both teachers and students, extracurricular offerings and/or elective courses can include increasingly interdisciplinary applications of core academic knowledge. (A middle school student has nominated the name "Innovation Agents" for an after-school offering and/or elective course.)

This curricular unfolding could resemble the adoption of a new technology, beginning with self-selecting early adopting teachers, and assuming continued curricular support of all teachers. Early adopting teachers are likely to become a rich source of curricular design and support, including likely participation in online communities of practice.

With time and intentional structures, the combination of intelligibility and practice is to train the eye, develop discerning imagination associated with pertinent knowledge, train the day-to-day impetus, cultivate passionate interests and signature strengths, and more. Students could become more aware of opportunities for learning and practice outside of school, including online communities of practice.

If intrinsic motivation takes hold, these young learners could help create fertile external conditions that support peers. In fact, they're likely to influence a learning system itself and to do so in big ways.

4. Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship within Higher Education"Better training, higher expectations, more accurate recognition, a greater availability of opportunities, and stronger rewards are among the conditions that facilitate the production and the assimilation of potentially useful ideas." [13]

This sketch is based on three fundamental ideas:

- that the power of social challenges calls for innovation methodology's full power, and thus for intentional, structured development of practitioners

- that valuable knowledge of social system "industries" (e.g., public health, education, natural resources, and economics) is located throughout existing university schools and departments

- that a sub-set of faculty and post-baccalaureate students in these areas are drawn to innovation methodology's focus on "integrating and applying knowledge," as a direct complement to research methods.

The sketch is not a blueprint. It's to put concrete ideas on the table as a suggestion of possibility. As an overview:

- The programming is conceived of as "innovation methods," which, akin to research methods, would modify varying primary fields of study.

- This particular sketch assumes graduate-level students with particular interest in social innovation.

- The overall learning objectives are: fostering intelligibility of social innovation and fostering capability for producing it.

- A multi-disciplinary center serves as a programming hub. This organizational structure is aimed at creating maximal value from, and for, dispersed human resources (faculty and students) and from dispersed knowledge resources. (As a new methodology, the hub also is to support faculty pioneers and a new generation of faculty.) The structure is facilitated by the modular interface provided by a developed version of innovation's first principles,

The sketch aims to support participation that is as broad and flexible as it is grounded. In the quest for advances toward societal goals, John Gardner advised: "Be hospitable … Nothing is more decisive for social renewal than mobility of talent."[1-1]Faculty and students could be affiliated with a range of disciplines, especially those associated directly with what might be considered the social production system's "industries" (e.g., public health, education, natural resource stewardship, economic development), but including disciplines that contribute specialized knowledge and skill across industries (e.g., information study and systems, management, engineering, and more).

The sketch addresses in turn:

- sample curricular substance

- the organizational model of a hub.

a. Sample Curricular Substance

Curricular substance, which would be woven into and throughout a set of innovation methods courses, is addressed within the subheadings of: foundational concepts, knowledge strands, hands-on practice, and discernment.

i. Foundational ConceptsSimilar to the way that the study of quantitative research methods begins with key concepts such as reliability, validity, and the Central Limit Theorem, begin by explicating foundational concepts within the context of first principles for innovation.

A potential "social differential" is fundamental.

For example, emphasize and/or explore:

See more.

- resource leverage overall and particularly in the social production system;

- the social production system and how it relates to, and overlaps with, the commercial production system;

- the fit of cultural, political, and socioeconomic dynamics, including poverty;

- innovation hypotheses;

- social innovation's offerings, including distinguishing between constants and variations;

- social innovation's "customers," including multiple levels of customers;

- the fit of value and values, with respect to both customers and practitioners;

- core strands of pertinent knowledge;

- how pertinent knowledge serves as capital and the locations of this knowledge (e.g. in humans, structures, and customers);

- leading examples of social innovation offerings across social "industries" (e.g, public health, education, natural resources);

- global dynamics;

- conceptualizations pertinent to social innovation offerings, which might include those originally associated with developing nations such as: "tiered pricing," "patient capital," and appropriate technology.

Draw on the unifying frame of developed first principles to situate (and to facilitate inclusion of) existing and emerging theories and bodies of knowledge. For example:

- positive psychology

- knowledge capital; knowledge management; "big data"

- design thinking

- development/design of offerings

- complex systems

- human development; principles of teaching and learning

- creative processing (from neuroscience, psychology, and more).

ii. Knowledge Strands

Overall, emphasize the fit of pertinent knowledge of the highest quality as capital within the practice of developing and deploying effective social innovation hypotheses.

In particular: "what" are the pertinent strands of knowledge, and "where" is it located?

What knowledge?

See more.

Sample elements of a base on which to continually build, organized by the prototype principles' thematic strands of pertinent knowledge:Industry/Operations -- This strand of knowledge is associated with the schools and departments most directly associated with the social production system's respective "industries" (e.g., health, education, natural resources).

The innovation methods programming is not a primary source for this knowledge strand, but rather draws upon the knowledge, emphasizing its focal fit.

For example, with resource leverage occurring within the production system's operations: What is the knowledge that supports the value produced by the social industry? What is the nature of the operations producing the value? Consider, for example, goals, structures, and "customers" :

- the source and nature of societal aims related to the industry

- structures and models of operations/enterprises to realize the aims (e.g., for-profit and nonprofit enterprises, government agencies and operational systems, foundations, and more)

- types and levels of "customers" within operations.

Customer Knowledge -- This begins with the innovator's view of all operational dynamics as transactions. Concretely, who are customers? What do they adopt as "value"? What value do they produce? How do social innovation's multiple types of change (adoption, behavior, and capability) relate to the customer segments/levels?

Human and Social Dynamics -- Consider, as Bruner put it, "how the world is put together from a human and social standpoint." Include leading sources of knowledge about human and social dynamics associated with value, social production, and leverage. Emphasize both enduring work (e.g., Foucault's Discipline and Punish) and emerging work (e.g., positive psychology's theory of well-being, Crossing the Chasm's pattern of adoption/change, etc.).

Anything & Everything -- With innovation hypotheses as new connections of knowledge, establish the fit of this thematic strand of knowledge in relation to the preceding strands.

Where is the knowledge located?

A lens such as the framework of "intellectual capital" speaks to locations and especially to the productivity of interplay among the locations.For this level of programming, an important structure is peer-reviewed academic research. This curriculum provides the time and place to become facile in accessing and interpreting research-based knowledge.

This fits within Clayton Christensen's conception of "integrating and applying" knowledge.

iii. Sample Hands-on Practice

Students' hands-on work focuses on the innovator's core practice of leveraging knowledge by developing and deploying effective innovation hypotheses, expressed as offerings.

Per the prototype principles, these hypotheses address:

- "what could be" -- an anchoring change-catalyzing value proposition

- "how it could become" -- associated hypotheses for an operational/business model

Regular opportunity for hands-on engagement is intended to bring to life as many foundational concepts as possible and can be supported by many existing and emerging innovation models and tools. In fact, the hands-on work can provide practice with selecting models and tools. (See quick reference to a mapping of the tools to the prototype first principles.)Hands-on engagement also can support finding a personal style of practice, based on varying approaches to the practice:

For example, Tom Kelley, co-founder of the design firm IDEO, emphasizes in his book,The Ten Faces of Innovation that there is more than one productive personal style of attunement to, and engagement with, innovation's purpose. Kelley presents ten different personal orientations (e.g., the anthropologist, the experimenter, the convener, the cross-pollinator) that can lead to the same fundamental sensing of "sharp edges" ... "crying out for improvement."[13-4]

Team work should be as cross-functional as possible, and some hands-on practice may benefit from purely individual work.

iii. Discernment

The prototype of innovation's first principles incorporates the thematic view among thought and action leaders that effective innovation hypotheses draw integrally upon practitioner discernment. For social innovation, discernment may be particularly multi-faceted -- encompassing, for example, creative discernment plus "wisdom" and moral bearings.

Fortunately, existing scholarship addresses the multiple aspects of discernment and its teaching. Curricula for social innovation methods should draw on the best resources available for this element of instruction.

See more.John Gardner's work provides at least one example of enduring influence. From 1964, Gardner's Self-renewal; the individual and the innovative society speaks to creativity's integration with the moral bearings for helping to lead societal renewal (including understanding the values of ~customers). For prospective practitioners, Gardner argued: “It is not exhortation they need but instruction”:

“(W)e must help the individual to re-establish a meaningful relationship with a larger context of purpose. … (O)ne of the reasons young people do not commit themselves to the larger social enterprise is that they are genuinely baffled as to the nature of that enterprise. … They do not see where they fit in. If they are to commit themselves to the best in their own society, it is not exhortation they need but instruction. … We must also help the individual to discover how such commitments may be made without surrendering individuality."[13-5]

Additional potential resources include:-- Sternberg incorporates his in-depth work on the topic of wisdom within the WICS model. In WICS, Sternberg's "balance theory of wisdom," includes balancing interests among varying stakeholders and balancing the short and long term.

Sternberg's body of work also addresses the teaching of wisdom.[13-6] On the importance of its cultivation, Sternberg notes: "Human intelligence has, to some extent, brought the world to the brink. It may take wisdom to find our way around it." [13-7]

-- Robert Quinn's model for "transformative" change also is pertinent, including its element of moral reasoning. Quinn's concept of leadership of, and participation in, change that is "inner-directed and other-focused" is fundamental to this web site's prototype of innovation's first principles for both commercial and social ends. His work, too, addresses development. [13-8]

-- Ideas expressed by innovation thought and action leaders, such as those below, could be linked to the learning tool of case studies (as opposed to curriculum-related theories or models):

- the force of "truth" (or a "truth force), associated in part with practitioner integrity and moral bearings;

- the function of empathy;

- the societal dynamic of "middle level" values, with citizens able to see their "infidelity" to those values;

- moral leadership, including moral reasoning;

- moral imagination.

Finally, social innovation's discernment includes judgement about fitting one's efforts into a broader context of efforts directed at social advances. For example, Bill Drayton has emphasized knowing what has been tried before; students should understand this as a standard of practice and also a valuable aspect of knowledge. Similarly, Gardner wrote:"Clearheadness does not slay dragons; it only spares us the indignity of fighting paper dragons while the real ones are breathing down our necks. But those are not trivial advantages."[15]

iv. Trajectories of Development

The curricular substance is to support trajectories of learning associated with the programming's dual learning objectives: social innovation intelligibility and capability. Sample trajectories might include:

Understanding and attunement to:

- "offerings" as innovation's form and "value" as offerings' rooting (with value determined by customers);

- social innovation's types of change (adoption, behavior and capability) and associated catalysts (customer utility and learning);

- innovation as a combined evaluative-generative practice (the expression of creativity for the domain of production systems);

- how innovation's many frameworks, models, and tools fit within the principles and practice;

- sensibilities about the operational contexts of innovation (the social production system, including governance arrangements), including the fit of innovation's practice throughout the system;

- "the many dimensions and dynamics" of the "human systems" at the frontline of the social production system; [13-3]

- innovation's key strands of pertinent knowledge (and sources);

- one's preferred approach(es) to innovation's purpose and methodology and an understanding of others' varying approaches;

- the function of internal and external conditions associated with creativity's practice;

- the function of personal values, including moral bearings, moral reasoning, "moral imagination," and understanding of moral dynamics vis-a-vis change.

- the function of personal passionate interests;

Drawing upon all of the above, sample trajectories of capability and internal resources include:

- developing and implementing innovation hypotheses, based on integrating and applying knowledge from multiple strands and sources, including from academic research;

- assessing and testing hypotheses

- co-creating offerings with customers

- interpreting research findings and generally relating the methodologies of research and invention to innovation's direct methodology;

- personal creative confidence and discernment;

- working within cross-functional teams;

- and more

c. Organizational Design

In this sketch, a multi-disciplinary hub provides for the above curricular substance.

A hub is to connect the highly dispersed human and knowledge resources associated with social innovation within a university and beyond (including those located at the frontline of the social production system).

A hub might resemble the organizational structure of the University of Michigan's Center for the Study of Complex Systems, with both core and affiliate faculty providing centralized programming for students from all areas of the university.

Facilitated by a developed version of first principles, a hub is to support collaborative programming and learning that is as grounded as it is flexible, dynamic, and generative. It's to support synergy. For example:

- A hub could serve as a university's center of intelligence for social innovation, facilitating the formation of human capital's communities of practice and the structural capital that provides for:

- rapid knowledge sharing

- collective knowledge growth

- shortened lead times

- more productive people[18]

- A hub could support highly customized value for students (the "customers" of this academic offering):

This follows from C. K. Prahalad and M. S. Krishnan's model for "maximal value" of "N=1; R=G," which emphasizes an ever-improving match between customer interests and global resources.

Total optimal value is realized when value is customized for every individual customer (N=1) by drawing on a global span of resources (R=G). [17] In the case of a hub for social innovation programming:

- "N" represents the base of "customers" (students enrolled in the program),

- "N=1" indicates that the target grain size for customized offerings is each individual customer (each student enrolled in the centralized programming),

- "R" represents resources available to create customized offerings, and

- "R=G" indicates that the relevant pool of resources for each customized offerings is global (all university resources pertinent to social innovation programming).

- A hub's maximal value may extend even beyond "customized" value, to synergy:

Synergistic connections among participating faculty may include particularly fertile research hypotheses related to innovation or innovation methods (e.g., hypotheses about what makes scaling educational offerings difficult).

The conditions that a hub provides for creativity could support all participants' internal conditions for creativity (and vice versa).

As a developing methodology, a hub could channel institutional commitment toward developing shared and robust understanding of "the principles that underlie the subject of social innovation and give it structure." This commitment would likely support the conversion from skilled craft to methodology, which in turn would likely support more productive overall practice.

A hub also could facilitate connections to other innovation programming and knowledge within a university and strategic links to resources beyond the university, whether labeled as innovation or not.

As one example, the prototype principles' emphasis on social innovation's frequent need for change in human behavior and capability came from a theme across sources. However, once developed, it brought to mind the existing academic field of "Health Behavior & Education." This developed scholarship and practice could hold useful seeds for a social innovation hub, including potential parallel labels for other social industries (e.g., "Schooling Behavior & Education" or even "Innovation Behavior & Education").

The visibility of a hub's social innovation programming and activity might provoke or inspire newly conceived research throughout a university, beyond a hub's core and affiliate faculty. Some of this scholarship might become intentionally channeled to complement and enrich social innovation's methodology. Similarly, existing pertinent scholarship could be channeled to the social innovation purpose.

See more.One primary opportunity for channeling existing scholarship may fit with the knowledge strand of "general human and social dynamics," which seems to be largely unexplicated within innovation's thought leadership. Development of this strand could continue the evolutionary reciprocity between social science and the production system preceded by:

- social science laying a foundation for market research;

- commercial entrepreneurship as a source of increasing transfer of the terminology and institutional structures to social domains;

- the tech industry foundations for customer "usability."

Finally, a hub could facilitate attention to the question of if, or how, the equivalent of "tech transfer' might work for social innovation. The transfer resource is likely to be pertinent for some proportion of new social offerings, for faculty and students alike, and perhaps increasingly so. For example:

See more.University of Michigan public health professor, Vic Strecher, described a challenging process of interacting with a series of incompatible venture capitalists prior to finding a productive match for the public health innovation that became commercialized successfully as Health Media. [19-1]

Similarly, the University of Michigan's 2010 recipient of the Technology Transfer Career Achievement Award noted in his acceptance comments that the engineering work he did in the 1980s didn't make the difference it might have given the then-absence of robust resources for technology transfer. One of the first questions for any newly conceived offering would be which production system makes sense: commercial or social.