Beam me up, Federico. These people seem unaccountably depressed. Worse still, when their economy begins to collapse, they’re likely to burst into a defensively concocted medley of popular songs with "be happy" lyrics. It’s more than anyone should have to endure. Curiously, those softshoe relics of ill-founded optimism have a special atomic weight that defies logic. It is tempting to imagine that if only they’d been able to stunt Shirley Temple’s growth—by prescribing a diet of grain alcohol and library paste, or with simple hormones and the fumes from lead-based paint—then maybe the candied innocence we so desperately wanted might have mutated into some sort of a reality. Apple pie and law ’n’ order would have held the world together and theatres would still have pit orchestras. Idyllic? You want idyllic?

Well, we wanted idyllic. So instead she grew a bosom, stubbornly advancing into adulthood through two marriages and eventually producing children—can you possibly handle that? Shirley Temple, that taphappy hermaphrodite, laying down and giving birth to offspring?! Traumas like this do put circles under mine eyes. And wait, there’s more! For years now we’ve had Ambassador Shirley, Republican Shirley, the Shirley of Tomorrow, all kinds of grim latter-day Shirley manifestations, while Shirley the Dancing Tot is lost somewhere back there in the grey shit gutters of the 1930s, and the world has continued to be a vicious mess. It’s not her fault.

When I was her age, I had her record. 20th Century Fox right on the label. It was the best I’d heard; more inside than Handel, less aggressive than Popeye, surely—I noted with relish what Mae Questel’s Olive Oyl voice could do to a room full of adults. There were hours to spend concentrating on the records and what they had to say each and every time. Shirley Temple’s movie soundtracks were the single most influential force in my formative years. 1963 introduced me to assassination and the art of tapdancing. I haven’t forgotten. Harpo Marx was more of a genuine role model and lives today inside my American eyeballs. I wouldn’t want to face this world without him. But Shirley handed me The Good Ship Lollipop, Baby Take A Bow, Animal Crackers In My Soup, You Gotta Eat Your Spinach Baby, and the very moving, anarchistic I Love To Walk In The Rain. With a Broadway chorus of adults chortling somewhere behind her, this little girl showed me that charming Ice Cream Surreality, so necessary for survival in this mangled Western existence.

Shirley Temple Black has an autobiography entitled Child Star, (McGraw-Hill, 1988), which is a goldmine of impressions and descriptions, swollen to more than five hundred pages. What possessed her parents, particularly her mother, to subject a child to the heinous peculiarities of showbusiness and especially the cinema? Many children have since been fed to the Beast; quite a few were devoured and spat out as wrecked anthropomorphic shadows who died off quietly. Shirley was fortunate to survive and evolve into an adult, nominally free of the entertainment industry. That industry has always teemed with nasty and tortuous doings. Kenneth Anger’s lively Hollywood Babylon is only the tip of a morbid iceberg. The most alarming thing I found in Shirley’s book was the description of a Black Box used to punish disobedient six-year-olds on the set of the Baby Burlesks. The soundproofed box was a mixing unit designed for technicians. One such chamber was empty except for a large chunk of ice. A refrigerated detention block. Didn’t the Nazis perfect this idea?

Shirley was banished, she says, into this grim cooler on several occasions. The contrast from being under hot lights to the nearly unventilated dungeon was very effective for discipline —yesiree— although she caught colds and flu from the chill. Shirley says that despite the cruelty involved, it taught her to obey instructions and not waste people’s time. Such rationale is very noble, but doesn’t excuse the abominable behavior of the adults in charge. Adults. The film scripts usually packed in several rotten examples, humorless miscreants who would invariably fuck things up right in the middle of a birthday party, just like real life. Even as a grown man I live by this message: Never trust adults unless they can tapdance. That’s what I got from the films, anyway.

True tapdancing is a way of thinking, of being. Shirley violated that principle straightaway when she befriended the nefarious and sociopathically driven J. Edgar Hoover, sworn enemy of the Kennedys, the same man who stated in public that organized crime wasn’t a problem in this country because it didn’t exist. Right. Just like the Warren Commission said that Jack Ruby had no discernable ties with the Mob, and it turns out that as a teenager, Ruby ran numbers for Al Capone. So much for the truth. In the nineteen thirties, Hoover had just begun to swell with power, and his worst angles were yet to sprout. Shirley liked to wear the badge he gave her. Everything seemed simple. It was a grown-up game of cops and robbers. But there was another adult who meant more to her than Hoover and his G-Men ever could.

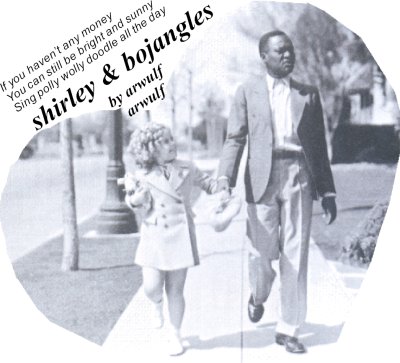

Shirley’s best friend was an adult tapdancer by the name of Bill "Bojangles" Robinson. They have been called the first inter-racial couple in motion pictures. The association with Hoover is easier to digest when we contemplate Shirley and Bill doing their stair dance in 1934’s motion picture The Little Colonel. This might seem like an Uncle Tom nightmare, but we really need to consider Bill Robinson in his own light. Bill Robinson coined the word copasetic when he was a kid shelling peas in the market. Asked how things were going, he emitted that word, which today can be found in the dictionary. Means everything is cool. Just fine thanks. I can cope.

Bojangles is the name he was presented with by his peers at about the same time as copasetic entered the language. Listen, these young people worked their butts off, doing most anything that would earn pennies. Dancing and singing were more fun than shelling peas, simple as that. A good dancer would see a lot of pennies hit the pavement. Bill developed a style. Vaudeville is frightening to look at if you consider the way people were yanked around. This racist entertainment racket came complete with performance parameters: Bill transcended them. There was some sort of a taboo about a single colored performer; had to be two or more. Bill established himself as a solo act. Doesn’t seem too incredible today, until you reconsider the nature of things back then.

Blackface was mandatory. You had to smear up with some sort of gick before doing your stuff. Degradation puts it mildly. Bill simply chucked the entire issue and went on and did his stuff. No need to even talk about it. Watch me dance. "As long as you like it, I can furnish it." Mr. Bojangles, The Biography of Bill Robinson, (by Jim Haskins and N.R.Mitgang, Morrow,1988) spells out every known fact concerning the man. Important to state here and now: the overplayed pop song "Mr. Bojangles" has positively nothing to do with Bill Robinson. This is a very important point, for Bill never lost his dignity, and the dancer depicted in the song had none left.

The contrasting parallel between Shirley and Bojangles is most evident in their relations with authorities. Why Shirley adored Hoover is beyond me. (Maybe she saw him as some sort of cartoon character made tangible.) Let’s just say she didn’t know any better. That’s safe. Bill Robinson figured out how to interact with the law early in his career, out of necessity. Immediately upon entering a new town, he would hasten to introduce himself to the chief of police, promising to help preserve law and order. It worked! In fact he became famous for his good relations with law officers throughout America. How did all of this get started? Let me tell you about it.

Bill Robinson wouldn’t take no shit from nobody. He’d enter any restaurant, regardless of its color bar policies, seat himself and order up a meal. If they were vulgar enough to try and refuse him service, Bill would calmly pull out his pearl-handled revolver, lay it on the table, and place his order again. This usually worked. It also usually brought in the law, whereupon Bill was recognized, and the proprietor would be scolded, until Bill spoke up and said: Hey. No sweat, no hard feelings, ease up: "Aw, g’wan. What’s the matter with that fellow anyway? That’s nothin’ at all."

Dizzy Gillespie, in his autobiographical study To Be Or Not To Bop, described how easy it was at first to resent Louis Armstrong, and to see him as an Uncle Tom, laughing and grinning and waving his handkerchief in the face of white racism. As time passed, Diz realized that Louis wasn’t just pretending that racism didn’t exist, but was demonstrating a special type of optimism, a strong stance which said "I’m going to keep shining no matter what happens, and nothing’s gonna pull me down." Now that’s beautiful. It’s Bill Robinson’s beauty, too. Hecklers are part of the performer’s existence. Bill had various methods for handling them. These ranged from politely ignoring the chumps, (resulting in overwhelming admiration from the rest of the crowd), to leaping right off the stage, collaring the offensive member, throwing his ass outside, returning to the stage and finishing the act as if nothing had happened.

A gentleman. Polite, well-mannered, and only volatile when racism reared up ugly in front of him. There’s the tale of an entire Negro theatre troupe being refused lodging during a dangerous blizzard in South Dakota. It was life and death, and Bill used his pistol that time, threatening to shoot anyone who tried to prevent them from finding shelter. That’s no Uncle Tom story. Charlie Parker and Bill Robinson committed almost identical acts of protest, years apart. Each man, finding himself in a racist setting, ordered a drink and then smashed the glass when finished. This was to emphasize the fact that a glass used by a Negro would not be considered reusable. Bill offered to pay for the glass. Bird pissed in the phone booth and walked out. Two generations. Parallel contrast again.

But listen to this one: In 1934, Bill attended a Civic Repertory Theater production of a play called Stevedore, depicting the struggles of a black dock worker who attempts to organize the workers. "It was a powerful play and contained a climactic scene in which the blacks barricade themselves behind barrels and mattresses and engage in brick-throwing and shooting with a group of white thugs." Now get this: "At one point in the third-act battle scene when the blacks were losing ground, he leaped out of his seat, took the stage steps three at a time, got behind the barricades, and started hurling bricks with the rest of them. The actors, aghast, stopped in mid-hurl; and Bill, suddenly aware of where he was, left the stage and returned to his seat. When the play was over, he was called back to the stage. He explained that he had ‘no conscious notion’ of what had happened. He did not apologize."

The trance-state has always been an integral force in theatre, most poignantly in the use of masks. Theaters themselves are wonderful and mysterious places, especially the elegant ones built during the first half of the century. To leap from one’s seat and join in armed struggle upon the polished floorboards of the stage is to grasp life by its truest fictions, asking without asking: where does the real world somersault into this alternate world, and when can we start to ACT? Action can be scripted, but even the most rigid implementation must be also improvised, or the theater will fill with brine, and the people turn to pickles. Pickles in the house, pickles under lights. Humor without spontaneity is not humor but horrible pickles. Vaudeville had its pickle people. Bill Robinson was light years ahead of most of them, able to entertain on his own wonderful level, where the corniest corn still had a noble, commanding air.

Bert Williams had similar powers. He too got by the Jim Crow inanities of the turn of the century, refusing to perform in blackface and developing a unique way of presenting himself. Bert worked with an orchestra behind him, commenting on everyday life in a disarming, quiet voice. Prohibition gave him plenty of subject matter, and titles like Everybody Wants a Key to My Cellar and The Moon Shines on the Moonshine are still worth listening to. Bert and Bill both made good money at a time when success was unthinkable, in most peoples’ minds, for people of color. Their successes helped to undermine the ethnophobia of showbiz. It took many years, but eventually the entertainment industry had to change its ways. Ray Charles had his challenges, but it would have been much more difficult for his generation if these Vaudevillians hadn’t taken those initial steps. Those giant steps.

Also: Bill taught Shirley Temple how to dance. The effect which this one achievement had upon the American public cannot be underestimated. As jaded as I may have sounded when discussing those "get happy" songs which were so popular during the 1930’s, there’s no denying the fact that completely unfounded optimism did in fact help to sustain large portions of the population. Listen: It’s about survival. The Pan-African experience demanded a willingness to survive. The art forms which grew out of that experience are among the most popular and exciting in the world. Reverberations extend into much of the mainstream of pop culture. What was it Rahsaan Roland Kirk told us before he died? There wouldn’t be no Linda Ronstadt if it weren’t for Bessie Smith! We ask you to study the sources.

Listen: Find the old records and hear where we’ve been. If you’re lucky you’ll even find one of the few recordings of Bill Robinson which still exist. Doin’ The New Low Down, (from Lew Leslie’s Blackbirds of 1928), recorded in 1932 with Don Redman’s Orchestra, gives the best taste of what he could do with his feet. It’s clog dancing, less ticky-tack than what you usually hear from, say, Fred Astaire. Fred was tremendous, but Bill had a down-to-earth approach all his own. Any opportunity to see the movies where Shirley and Bojangles sang and danced together should not be passed up. Most of the scripts are blood-curdlingly stupid, and there’s no escaping the grimly sugared vestments of Hollywood. But I’m like Charles Bukowski in that I cry at Shirley Temple movies. Something about innocence that wasn’t ever really there, Little Miss Broadway urging us to be optimistic and smile, even if Daddy has a hole in his head and can’t recognize you as he peers out from under the bandages. Just smile and hoof a little and see what happens.

Reality? Did someone ask for a reality? Here? The blueprint for survival that lives in the Blues: maybe you’re Sittin’ On Top Of The World or you tell yourself you’re sure that The Sun’s Gonna Shine In My Back Door One Day—maybe those are earthier and more timeless ways of standing strong, and maybe I’m crazy to compare. Cinema of the 1930’s has more of the cheesy cardboard and lace construct; the empty box of chocolates still looks good on your shelf, you leave it there to gather dust, next to the photo of Shirley in its cheap, gold painted frame. The record is cracked and broken. Listen deep. These are our traces. Evidence. All sorts. But it’s all part of the same reality, a century of unprecedented leaps and bounds, where with every giant step you find yourself wondering if you’ve gotten anywhere at all.

Garcia Lorca will have the last word:

The theatre is a school of laughter and lamentation, an open tribunal where the people can introduce old and mistaken mores as evidence, and can use living examples to explain eternal norms of the human heart. The theatre is an extremely useful instrument for the edification of a country, and the barometer that measures its greatness or decline. A sensitive theatre, well oriented in all its branches, from tragedy to vaudeville, can alter a people’s sensibility in just a few years, while a decadent theatre where hooves have taken the place of wings can cheapen and lull to sleep an entire nation.

Federico Garcia Lorca

"A Talk About Theater", 1935

arwulf

1992/2001

Signed Elements ©

Individual Authors

Unsigned Elements © Agenda Publications, LLC