Scott D. Campbell (home page)

Associate Professor of Urban Planning

Taubman College of Architecture + Urban Planning

University of Michigan

2000 Bonisteel Blvd., Ann Arbor MI 48109-2069

sdcamp@umich.edu

modified:

Thursday, May 13, 2021

Basic Information

The exam is a take-home written examination, generally taken over a three-day period (followed by a two-hour oral exam, to take place about one week later). You should complete your comprehensive exam by late May after your fourth semester in the doctoral program (see deadline info below). After you have successfully completed your required coursework and comprehensive exam, you are ready to advance to candidacy.

Suggested Timeline

Winter (year 1) or Summer (after year 1)

Fall (year 2)

Winter (year 2)

Spring/Summer (after year 2)

The following are a list of suggested steps to prepare for the Comprehensive Exam. However, you should directly discuss the examination procedure with your advisor and committee members.

Before the Exam: Form a committee, articulate your areas of specialization and write a “field statement”

1. The student convenes an examination committee of three faculty members, choosing faculty who have expertise in the areas of specialization. (Form your committee by the fall semester of your second year.) At least one member of the committee should be a member of the urban and regional planning faculty. The chair or co-chair of the committee must be a regular member of the URP faculty and cannot be an affiliate faculty member. At least one committee member should represent the student’s secondary area of specialization. (If the student has identified a secondary area of specialization that is traditionally housed in another department on campus, then the student is encouraged to select a faculty member from that outside department as their third committee member.) On occasion, examiners from outside the university have served on students’ examining committees. While this practice is generally discouraged, written requests for an outside examiner by students are treated on an individual basis by the Director of Doctoral Studies.

Start this process early. Meet with the committee members at least several months before the exam to discuss (a) the scope and boundaries of the subject matter; (b) readings; (c) hypothetical exam questions; and (d) their expectations for the exam process. Optional: You may decide to convene a meeting with your entire exam committee to discuss the major themes and readings for the exam area.

2. Articulate your Primary and Secondary Areas of Specialization

Primary Area of Specialization

Students are expected to demonstrate an understanding of the literature, theory, and methods from a primary area of specialization. Each student defines this area of specialization in consultation with his/her faculty advisor(s). An area of specialization might be, for example, transportation planning, community development planning, regional planning, environmental planning, and so on. (If appropriate, a student may further focus their area of specialization by demarcating a subfield within a broader planning topic, such as economic development finance within local economic development.) We recommend that you already begin defining your specialization during the first semester in the program. To this end:

Secondary Area of Specialization

In addition to the primary area of specialization, each student must also identify a secondary area of specialization (i.e., a “minor field” or “outside field”) in consultation with his/her faculty advisor(s). The secondary area of specialization is frequently from a discipline outside urban and regional planning (examples include urban politics, urban history, urban sociology, demography, development economics, environment and behavior, etc.). Students normally take at least six to nine credit hours in this secondary area. Students demonstrate sufficient knowledge in this secondary area (and their ability to integrate the secondary area into their main area of specialization) through their comprehensive examination.

3. Prepare a "Field Statement" and give each member a copy. Expand and revise this statement as an integral part of your exam preparation. (You will likely build upon work done in your directed study with your advisor.) See this folder for previous examples. This statement contains several parts:

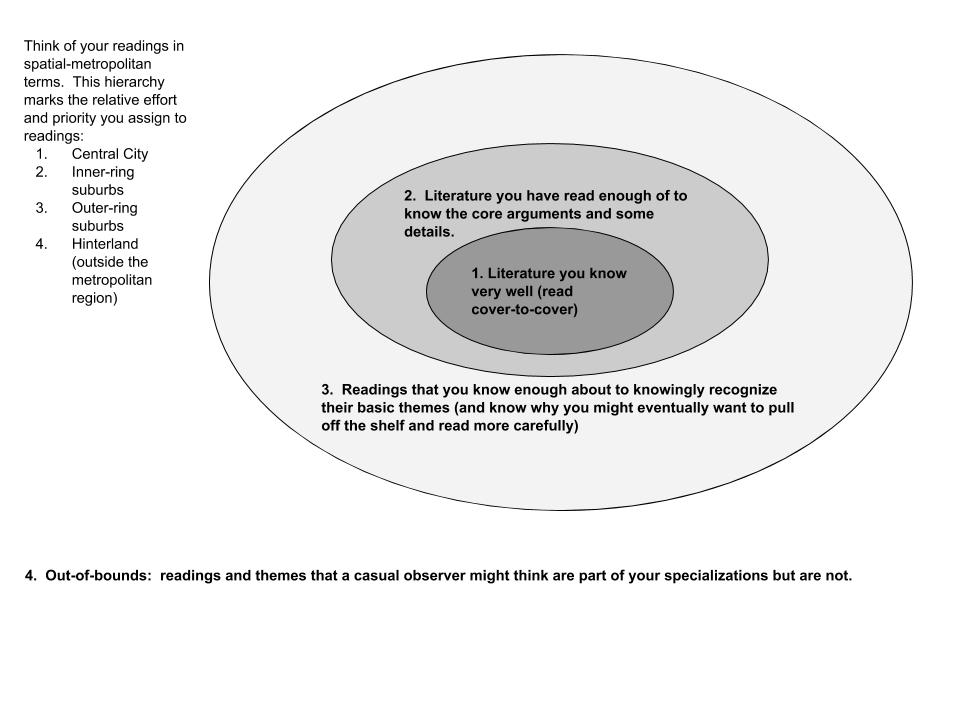

a. a concise definition and overview of both the primary and secondary fields: the defining questions of the field, the disciplinary influences, the major debates, the organization of the field and its subfields (1-3 pages). [Note: in some cases it is useful to not only define what is inside the boundaries of the field, but also what is OUTSIDE the field – as you have defined it. You might break this into three categories: (a) core readings and themes; (b) supplemental readings and themes; and (c) readings and themes that you do NOT expect to be tested on.]

b. a bibliography of the field. Divide the readings into sub fields. (I would suggest using Endnote, Mendeley, RefWorks or some other bibliographic program, though this is not necessary. Citation managers can be really useful once you start writing your dissertation.)

Scheduling the Exam & Deadline: Prior to the exam, the student should have completed all coursework, including all incompletes. The comprehensive exam must be satisfactorily completed no

later than five weeks after the last day of classes of Semester 4 (typically at the end of winter

term of the second year. The date is approximately May 25 if Semester 4 is the winter term,

approximately January 20 if Semester 4 is the fall term). (A “conditional pass” on the exam does not satisfy this requirement.) Well before the exam, students should notify the doctoral director of their exam dates, fields of specialization and names of committee members.

The written part of the exam is in the form of a take-home essay exam. The committee chair solicits exam questions from the committee, selects questions to be used, and composes the final examination. The allotted time period to write the exam is determined by the chair, and typically is over three days. (Sample format: the committee chair emails the exam questions to the student at 9:00 am on a Monday. The student then emails the answers back to the committee members by 5:00 pm on Thursday.)

This is followed by an oral exam, generally scheduled to take place one to several weeks after the written exam. The exam is evaluated on a “Pass/Fail” or “Conditional Pass” basis. If the student does not achieve a passing evaluation, he/ she may take the exam one additional time to achieve a “Pass” or “Conditional Pass” status. A “Conditional Pass” indicates that additional requirements must be met, but the exam need not be retaken. Upon completion of the oral portion of the exam, the committee chair will send a “Comprehensive Exam Certification Form” to the Director of Doctoral Studies.

1. For each question, develop a central thesis and justify it with a logical argument. Be sure to answer each part of the question. Be explicit about any assumptions you make in interpreting the intent of the question.

2. Don't spend so much time writing the first question that you are left with too little time for the remaining question(s). Allocate enough time for each question, and allow time to go back to edit and proofread. Write one essay per day, and use the partial final day to edit/proofread.

3. Properly cite the relevant literature. This applies to both citing direct quotes and broader ideas. However, we do not primarily evaluate the exam based on your use of references. Of greater importance is your ability to identify, analyze and compare the competing concepts and theories in planning. We look for an ability to intelligently discuss the most important questions in the field.

4. There is usually a suggested page limit, such as 10-12 double-spaced pages per question or perhaps 30-36 pages for the entire exam (not including the bibliography).