An IMS for Management and Control

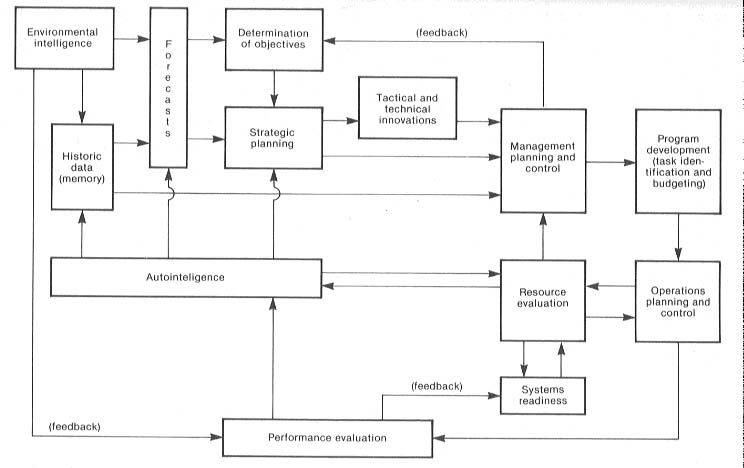

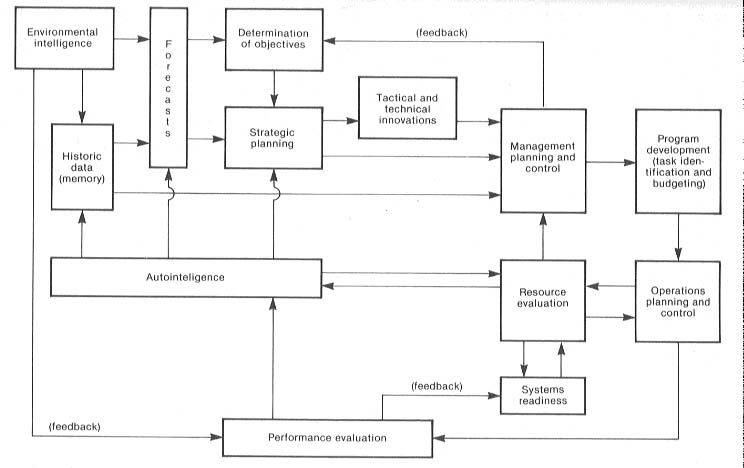

The basic components of an IMS applicable to the information needs of financial planning and management control are illustrated in Exhibit 2. Three specific data areas provide inputs for the formulations of strategic decisions: (1) environmental intelligence--data about the broader environ-ment of which the organization is a part, including assessments of client needs; (2) autointelligence--data about the component elements of the particular organization, including an evaluation of organizational resources and its capacity to respond to client needs; and (3) historic data, which bring together and analyze the lessons of past experience. These data are stored in the memory banks of the organization to be retrieved when particular decision situations arise or when a broader assessment of the overall goals and objectives of the organization is appropriate.

Exhibit 2. Components of an Information Management System

Basic research and analysis are essential to effective fiscal planning and management control. Data must be systematically collected and stored for future use and reference. Data can be generated externally (e.g., macro-trend analyses, Census data, etc.) or internally (e.g., accounting and other fiscal management data). Basic analysis can be carried out using various modeling programs available in a well-constructed IMS. The results can be stored in the data base for reference and updating. The diagnosis of trends can be aided, in part, by the modeling and simulation programs and statistical analysis packages. This aspect can be facilitated by programs that perform functions related to systems analysis and operations research.

Forecasts of the probable outcomes of events can be developed on these data foundations. Probable happenings are outlined by assuming the continuance of existing trends into hypothetical futures. These forecasts provide an important inputs in determining organizational objectives--an initial impetus for strategic planning.

While computer-based data have not been used extensively in the formulation of goals and objectives, an IMS can aid in the development and evaluation of such statements. Objectives can be written so as to take fuller advantage of available information in the system. Additionally, written objectives can be stored, permitting easy access, change, and output. Once objectives have been determined (at least in preliminary fashion), the planning process can begin to suggest possible directions that the organization can take in response to client needs in the broader environment. Two important initiatives are important in this regard: (1) the search for possible new courses of action to improve the overall performance of the organization; and (2) a framework for resource management and control.

The same system components used in the basic research and analysis phase can be applied in the formulation and analysis of alternatives. The analysis of alternative must build on the basic analyses previously carried out, and therefore, significant use must be made of the storage and query capabilities of the DBMS. The results of previous decisions and program actions are combined through policy and resource recommendations. In this capacity, the IMS can be useful in the storage and retrieval of needed information and in report generation.

Tactical and technical innovations must be sought to improve the overall responsiveness of the organization (in the private sector, these innovations also improve the competitive position of the organization). Various "what if" scenarios may be tested through the analytical subroutines contained within the IMS.

Management plans must translate the overall intent of strategic plans into more specific programs and activities. These management plans are both information demanding and information producing. The budget process provides important managerial feedback in terms of evaluations of prior program decisions and actions. Feedforward informa-tion emerges from the various projections and forecasts that are required by financial analysis and budgeting processes.

Management control activities draw on the memory banks of the organization in search for programmed decisions--decisions that have worked successfully in the past. Timely resource evaluations also provide important inputs into the management control process. These evaluations include information regarding the current fiscal status of the organization (accounting data), as well as the overall response capacity of other organizational resources (systems readiness). The fiscal planning and management control processes should provide critical feedback to the further refinement of objectives. In some cases, this feedback will require a recycling of the processes before proceeding to the next phase.

Program development involves the activities of task identification and budgeting. Specific operations are detailed within the framework provided by the strategic plan and fiscal planning decisions. Responsibilities for carrying out these operations are assigned, as are the resources required by these operations. Specific operations may be further detailed through the procedures of operations planning and control (which may include such techniques as Program Evaluation Review Technique (PERT) and Critical Path Method (CPM)). Programming and scheduling procedures usually require further information regarding resource capabilities. They also may precipitate a recycling of the fiscal planning process.

The final component of the IMS involves the information derived from performance evaluations. Performance evaluation draws data from the broader environment regarding the efficiency and effectiveness with which client needs are met, problems are solved, opportunities are realized, and so forth. Some writers view performance evaluation as a separate process outside the management information system. Others recognize the importance of incorporating the data and information developed through such evaluations by referring to a management information and program evaluation system [1]

A basic problem of organizations today--whether in the public or private sectors--is to achieve an appropriate balance in programs and decisions to ensure systems readiness. Systems readiness defines the response capacity of the organization in the short-, mid-, and long-range futures. Sufficient flexibility is required to meet a wide range of possible competitive actions. The development and maintenance of an IMS that includes the basic components outlined herein can contribute significantly to meeting this challenge.

Feedback is a basic requirement of any IMS. Feedback must be obtained in terms of quality (effectiveness), quantity (efficiency of service levels), cost, and so on. Programs must be monitored to maintain process control. Evaluations of resources (inputs) provide feedback at the earliest stages of program implementation.

Feedback data must be collected and analyzed at various stages in the implementation of programs and the maintenance of ongoing operations. These analyses involve processing data, developing information, and comparing actual results with plans and expectations. Routine adjustments may be programmed into the set of ongoing procedures, and instructions can be provided to those individuals who must carry out specific tasks. Feedback from the operating systems provides an information flow within the management control procedures to initiate and implement program changes in a more timely basis. Thus, procedures are modified and files updated simultaneously with routine decision making and program adjustments.

Summary and exception reports may be generated by the IMS and become part of higher-level reviews and evaluations. These evaluations, in turn, may lead to adaptations or innovations of goals and objectives. Subsequent management activities should reflect such feedback, and the entire process is recycled.

Managers must seek data and information that will permit actions to be taken before problems reach crisis proportions. Historic data provided by conventional accounting systems may be insufficient to meet these decision needs (even when the time lag is only a few weeks). Resource evaluations on the input side and resource monitoring as programs or projects progress can provide the more timely information required to anticipate rather than merely to react to problems.

An information system appropriate for fiscal planning and management control must use feedforward as well as control based on feedback. Feedforward anticipates lags in feedback systems by monitoring inputs and predicting their effects on output variables. In so doing, action can be taken to change inputs and, thereby, to bring the outputs into equilibrium with desired results before the measurement of outputs discloses a deviation from accepted standards.

In time, an organization "learns" through the processes of planning, implementation, and feedback. [2] Approaches to decision making and the propensity to select certain means and ends change as the value system of the organization evolves.

Endnotes

[1] For a further discussion of the concepts of MIPES, see: Alan Walter Steiss, Public Budgeting and Management (Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books, D.C. Heath, 1972), chap. 10

[2] Richard M. Cyert and James G. March, A Behavioral Theory of the Firm (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1963), p. 123.