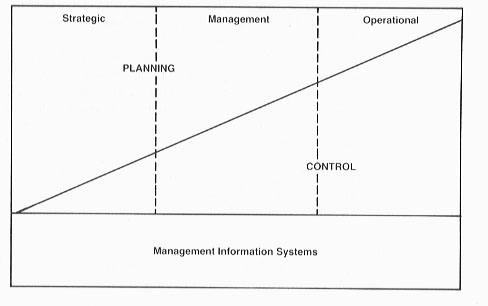

The Planning-Control Continuum

The basic objectives of financial management define a planning-control continuum (Exhibit 17). The principles and techniques of financial management have traditionally been closely linked with and have contributed significantly to the objectives of organizational control. However, to be responsive to changing needs of both the organization and the broader environment (e.g., client groups or the general public), financial management procedures must also incorporate a planning perspective. As Gannon has observed: "planning and control are intimately related and, in fact, represent opposite sides of the same coin. Without planning, there can be no control." [1] Without planning, control can do relatively little to reduce the uncertainty that surrounds many of organizational activities. While organizational programs may be carried out more efficiently, more important issues of effectiveness--the ability to achieve long-range objectives--may be left largely unresolved.

Exhibit 17. The Planning-Control Continuum

Planning Defined

It has been said that: "If you don't know where you are going, any road will get you there." There is also truth in the notion that: "If you don't know where you are going, no road will get you there." In short, planning is a prerequisite for effective financial management, whether in the private or public sector. Kast and Rosenzweig have defined planning as:

. . . the process of deciding in advance what is to be done and how. It involves determining overall missions, identifying key result areas, and setting specific objectives as well as developing policies, programs, and procedures for achieving them. Planning provides a framework for integrating complex systems of interrelated future decisions. Comprehensive planning is an integrative activity that seeks to maximize the total effectiveness of an organization as a system in accordance with its objectives. [2]

Traditional planning efforts have tended to be "one-shot optimizations," drawn together periodically, often under conditions of stress. Under such circumstances, problem-solving often takes precedence over the establishment of long-range goals and objectives. Program proposals frequently are based on "anticipated economic and demographic conditions"--a simple extrapolation of the status quo. When the overriding focus is on solutions to more immediate problems, the cumulative process becomes short-range planning albeit applied to a long time period. The results, benefits, and profits to be gained from such short-range plans cannot be assured in the long run and, in fact, may be lost in the crisis of disjointed problem-solving. A plan is of relatively little value if it does not look far enough into the future to provide a basis on which change can be logically anticipated and rationally accommodated.

It has been said that: "Few plans survive contact with the enemy." And indeed, rarely are policies and programs executed exactly as initially conceived. Random events, environmental disturbances, competitive tactics, and unforeseen circumstances may all conspire to thwart the implementation of plans, policies, and programs. In short, the traditional planning process does not provide an adequate framework for more rational decisions about an uncertain future. Fixed targets, static plans, and repetitive programs are of relatively little value in a dynamic society.

Strategic Planning

The concept of strategic planning has evolved over the past two decades as a response to this need for a more dynamic planning process--one which would permit continued efficacy of decisions to be tested against the realities of current conditions and, in turn, corrected and refined as necessary. As applied in government, it has been suggested that strategic planning: "is the process of identifying public goals and objectives, determining needed changes in those objectives, and deciding on the resources to be used to attain them. It entails the evaluation of alternative courses of action and the formulation of policies that govern the acquisition, use, and disposition of public resources." [3]

The term "strategic" has been applied to these planning activities to denote the linkage with the goal-setting process, the formulation of more immediate objectives to move the organization toward its goals, and the identification of specific actions (or strategies) required in the deployment of organizational resources to achieve these objectives. The term also was adopted to distinguish the scope of this process from the so-called "planning" which characterized much of the forecasting and other piece-meal efforts undertaken by industry and business concerns.

Strategic planning should be a continuous process which includes performance evaluation and feedback. Alternative courses of action should be examined, and the impacts and consequences that are likely to result from their implementation should be evaluated. Explicit provision should be made for dealing with the uncertainties of probabilistic futures. Major priorities should be identified and ordered, and the activities and functions of the organization can be integrated into a more cohesive whole.

The emphasis in strategic planning is on an orderly evolution--from a broad mission statement, to statements of more specific goals and objectives consistent with the organization's mission, to more explicit policies and implementing decisions. This emphasis seeks to establish or reinforce linkages that often are missing in more disjointed, incremental approaches to decision-making.

Management Planning

The good intentions of a strategic plan are likely to go unrealized unless the planning process is further extended to include the techniques of management planning. The objective of management planning is to organized and deployed resources effectively and efficiently in the accomplishment of organizational objectives. It involves: (1) the programming of approved goals and objectives into specific projects, programs, and activities; (2) the procurement and budgeting of necessary resources to implement these programs over some specific time period, and (3) the design and staffing of organizational units to carry out approved programs. Ideally, management planning forms the link between strategic goals and objectives and the actual performance of organizational activities--a mechanism for coordinating the sequence in which activities must be performed to complete a given program or achieve an agreed-upon objective.

Operational Planning

Operational planning focuses on setting standards for the use of specific resources and on performance tactics to achieve overall goals and objectives of the strategic and management plans. Operational planning is concerned primarily with the scheduling of detailed program activities. Scheduling determine the calendar dates or times that resources will be utilized according to the total resource capacity assigned to the program. A schedule can be developed only after the management plan is complete. Resource availability, task or job sequence, resource requirements, and possible starting times for the project or program activities must then be taken into account in order to produce a schedule.

Effective and comprehensive strategic planning may mean the difference between success and failure in the delivery of vital services. Successful management planning can mean the difference between the effective utilization of scarce resources and waste. Effective and efficient operational planning can mean the difference between "on time" and "late" in the achievement of a specific project.

Organizational Control Defined

Some form of control has been exercised for as long as formal organizations have existed. However, increased emphasis on account-ability, efficiency, and effectiveness in both the public and private sector has made the adoption of more effective control techniques even more imperative.

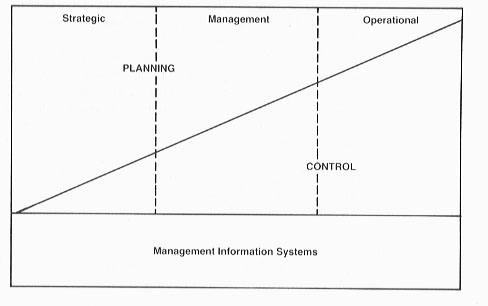

The control system can provide tools for determining whether an organization is proceeding toward established objectives and can alert decision makers when actual performance deviates from the planned performance. These procedures also can help to measure the magnitude of the deviations and to identify appropriate corrective actions to bring the activities back on course. Control involves six interrelated activities, as shown in Exhibit 18.

Exhibit 18. The Management Control Cycle

Strategic Controls

Strategic controls are used to evaluate the overall performance of an organization or a significant part thereof. In the private sector, standards such as profitability, ratio of assets to liabilities, and sales growth provide a broad basis on which the assess the overall performance of an organization. In recent years, standards applicable to public sector activities have been detailed in terms of measures of effectiveness.

When an organization fails to meet such broad standards, the remedies may have to be equally broad. They may include the recasting of goals and objectives, a reformulation of plans and programs, changes in organizational structure, improved internal and external communications, and so forth. Strategic controls are needed to assist decision makers in determining appropriate corrective actions when unanticipated changes occur in the broader environment of the organization. A strategic control system provides a basis by which the desired goals and objectives and the methods of control can be modified. Since large amounts of data may be required to achieve effective strategic control in complex organizations, continuous monitoring of activities through the application of manage-ment controls may be more appropriate to ensure that corrective action is taken on a timely basis.

Management Controls

Management control involves the measurement and evaluation of program activities to determine if policies and objectives are being accomplished as efficiently and effectively as possible. Management control provides the basic structure for coordinating the day-to-day activities of an organization, encompassing all those activities involved in ensuring that the organization's resources are appropriately used in the pursuit of goals and objectives.

Accounting and finance departments traditionally have served as the primary locus of the management control functions in most organizations. Information provided by an accounting system is designed to serve the needs of internal decision making as well as external financial reporting. This information can also provide a significant component in contemporary management control systems. Output from the accounting system, for example, can provide managers with important performance-measurement information as decisions are made and actions taken that are expected to lead to desired results.

Management controls are often designed to anticipate and identify problems before they happen. An obvious approach to try to anticipate possible deviations from some established standards or criteria of performance. This is the primary objective of statistical quality control. This approach also can be applied as a budgetary control. The possibility that a major proposed expenditure might exceed the budget, for example, should be ascertained ahead of time rather than after-the-fact. Such controls involve various forecasting and projection techniques.

Operational Controls

Operational controls seek to assure that specific tasks or programs are carried out efficiently and in compliance with established policies. These processes involve a determination of requirements for program resources and their necessary order of commitment to achieve specific program objectives. It often is difficult to distinguish between management control and operational control. Techniques used initially for management control may become even more significant when converted to operational control purposes.

Operational controls focus on specific responsibilities for carrying out those tasks identified at the strategic and management control levels. These control techniques must provide management with the ability to (1) consider the costs of other program alternatives in dollars and time; (2) establish criteria for resource allocation and scheduling; (3) provide a basis for evaluating the accuracy of estimates and the effects of change; and (4) assimilate and communicate data regarding program activities and revise/update operational plans.

Operational controls often are very specific and situation-oriented. They measure day-to-day performance by providing comparisons with various criteria to determine areas that require more immediate corrective actions. Productivity ratios, workload measures, and unit costs are examples of such performance measures. Such measures are concerned most frequently with issues of efficiency and economy.

Efficiency Versus Effectiveness

The term effectiveness relates to the accomplishment of an organization's goals and objectives. An organization is effective when its goals and objectives are accomplished; it is ineffective when they are not. The concept of efficiency, on the other hand, is linked to the use of organizational resources. When fewer resources are used to accomplish the same results, or when additional results are attained using the same resources, then a program or set of activities is said to be more efficient. Both efficiency and effectiveness are paramount objectives of planning and control.

Managers make use of goals, objectives, plans, programs, budgets, and various types of organizational, operational, and financial controls in carrying out their responsibilities. Thus, while planning and control form a continuum, the relative mix may be determined by management styles and the complexity of organizational structure. The planning-control continuum will be applied in the following sections to further delineate the basic components of financial management.

Essential tools for financial management must include techniques for assessing the long-term needs of an organization and its clientele, rational procedures for acquiring and allocating the resources necessary to meet these needs, and appropriate mechanisms for managing costs, maintaining accountability, and disseminating relevant financial information.

Information Management Systems

Effective financial planning and control requires timely and relevant information to understand the circumstances surrounding any issue and to evaluate alternative courses of action to resolve any problem. Information is incremental knowledge that reduces the degree of uncertainty in a particular problem situation. What constitutes management information depends on the problem at hand and the particular frame of reference of the manager. The fundamental objective should be to enhance the attributes of good decision making by providing quality of information rather than quantity of data.

Information is incremental knowledge that reduces uncertainty in particular situations. Although vast amounts of facts, numbers, and other data may be processed in any organization, what constitutes management information depends on the problem at hand and the particular frame of reference of the manager

Information consists of data that have been classified, categorized, and interpreted and are being used for decision making. In addition to storing raw data, an information management system (IMS) is a repository for information by which decisions can be tested for acceptability.

Contemporary management activities are both information-demanding and information-producing. An IMS must provide important feedback--soundings, scanning, evaluations of changing conditions that result from previous program decisions and actions. The specific objective of an IMS is to communicate information in a synergistic fashion--where the whole becomes greater than the sum of the individual parts.

Information management systems are composed of data bases--collections of structured and related information stored in the computer--data base management systems (DBMS)--software packages that provide the means for representing data, procedures for making changes in these data (adding to, subtracting from, and modifying), methods for processing raw data to produce information, and the necessary internal management functions to minimize the user effort to make the system responsive. Computer hardware should be the last matter to be considered in designing an information management system. It first is necessary to decide what kind of information is needed--how soon, how much, and how often.

An information management system must be flexible and adaptive and must have the capacity to accommodate deficiencies as the system evolves. Procedures must be developed to detect such deficiencies and to make adjustments in the information system so as to eliminate or reduce them to manageable levels. Many managerial decisions require explicit attention to nonquantifiable inputs, as well as to data that may result from computerized applications. Many excellent information management systems are based on relatively simple local data-processing operations, tailored to particular user needs.

Contemporary financial management activities are both information-producing and information-demanding. Important managerial feedback--soundings, scannings, and evaluations of changing conditions resulting from previous program decisions and actions--must be available to facilitate timely and effective decision making. Financial management procedures generate information that feeds forward to provide a basis for more informed decisions and actions over a range of time periods, locations, and perspectives. "Feed forward" information emerges from projections and forecasts; goals, objectives, and targets to be achieved; program analyses and evaluations; and the projection of outcomes and impacts of alternative programs. The objective is to satisfy the increasingly voracious appetite for management information applicable to strategic decisions, while reducing the cost of management in relation to total organizational costs.

| Director of Finance | ||||

| Handles debt administration | Supervises all finance activities

Advises Chief Administrator on fiscal policy Manages retirement & other city investments |

Makes interim and annual financial reports | ||

| Controller | Assessor | Treasurer | Purchasing Agent | Budget Officer* |

| Division of Accounts | Division of Assessments | Treasury Division | Purchasing Division | Budget Division |

| Keeps general accounting records

Maintains or supervises cost accounts Preaudits all purchase orders, receipts, and disbursements Prepares payrolls Prepares & issues all checks Bills property & other taxes, special assess- ments, and utility & other service charges Maintains investory of all municipal property |

Makes studies of property values for assessment purposes

Prepares & maintains property maps & records Prepares assessment roles Assesses property for taxation Distributes special assessments for local improvements |

Collects all taxes, special assessments, utility bills

& other revenues

Issues licenses & permits Maintains custody of all city funds Disburses city funds on proper vouchers or warrants |

Purchases all materials, supplies, & equipment

for city departments

Establishes standards & prepares specifications Tests & inspects materials and supplies purchased by the city Maintains warehouses and central stores system Provides certain central services such as mailing, duplication, etc. Administrers city's insurance program |

Conducts studies for development & administration

of budget system

Assembles budget estimates & assists Chief Administrator in preparation of budget document Acts as agent of Chief Administrator in controlling the administration of the budget by executive allotments, etc. Conducts studies relative to improvements in administrative organization & procedures |

*The Budget Officer often is responsible directly to the Chief Administrator, being physically located in the Finance Department to minimize duplication of records. In many cities, the Finance Director also serves as the Budget Officer.

Organizing for Financial Planning and Control

The financial planning and control responsibilities of any public organization should be under the general direction/supervision of the chief executive so as to promote full consideration of these vital functions. The chief executive has overall responsibility for: (1) formulating long-range plans for the entire organization; (2) preparing and administering the annual and capital budget; (3) maintaining the financial reporting activities; and (4) developing related systems for measuring program accomplishments. Most public organizations also have a governing body--for example, a board of directors, city council, board of commissioners. This governing body: (1) determines overall fiscal policy; (2) approves the budget for the organization; (3) adopts revenue and expenditure authorization measures; and (4) holds the chief executive accountable for the effectiveness of fiscal procedures and program results. Both the chief executive and the governing body must exercise financial stewardship in the conduct of these important fiscal affairs.

It is important to have a competent, well-organized financial management staff to carry out these responsibilities. Although good results are not necessarily guaranteed by sound organizational arrangements, past history has demonstrated that inappropriate assignments of financial planning and control functions can create serious problems and impede effective leadership.

The distribution of financial planning and management responsibilities within local government may vary considerably, depending on the size and form of govermnment, existing legal parameters in state and local laws and ordinances, past practices and traditions, and the management styles of those individuals with overall executive responsibility. A model organization for the financial operations of local government was first recommended by the National Municipal League in 1941 as part of its Model City Charter. This model has remained fairly stable over the past fifty-five years, as evidenced by its inclusion a recent publication on municipal finance of the International City/County Management Association (ICMA). This model reflects an emphasis on the strong mayor or manager-council form of government, with its increased centralization of management responsibilities.

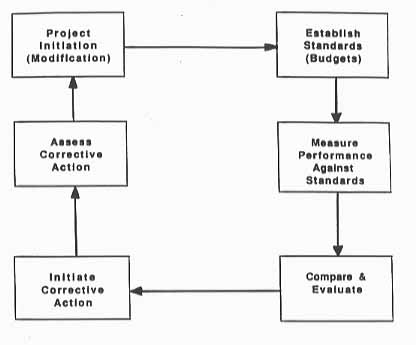

Except for the independent audit function, all financial operations under this model are grouped into a single organization--a Department of Finance--directly responsible through its director to the chief executive (see Exhibit 19). Financial responsibilities are distributed among five offices: Controller, Treasurer, Assessor, Purchasing Agent, and Budget Officer. The Budget Office may operate as one of the divisions of the Department of Finance or as a separate unit directly responsible to the chief executive. This latter arrangement reflects the policy emphasis of the budget as contrasted to the line emphasis of the other divisions.

Endnotes

[1] Martin J. Gannon, Management: An Organizational Perspective (Boston: Little, Brown, 1977), p. 140

[2] Fremont E. Kast and James E. Rosenzweig, Organization and Management (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979), pp. 416-417.

[3] Alan Walter Steiss, Public Budgeting and Management (Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books, 1972), p. 148