Financial

Planning and Managament in Public Organizations by Alan Walter Steiss

and Chukwuemeka O'C Nwagwu

Financial

Planning and Managament in Public Organizations by Alan Walter Steiss

and Chukwuemeka O'C Nwagwu Financial

Planning and Managament in Public Organizations by Alan Walter Steiss

and Chukwuemeka O'C Nwagwu

Financial

Planning and Managament in Public Organizations by Alan Walter Steiss

and Chukwuemeka O'C Nwagwu

MANAGERIAL AND COST ACCOUNTING

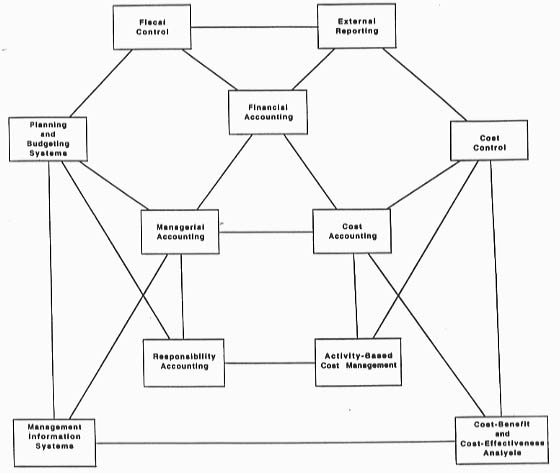

Financial accounting is concerned primarily with the accurate and objective recording of fiscal transactions and with the preparation of financial reports largely for external distribution. Although these traditional outputs of financial accounting may be used to guide certain types of internal decisions, many management decisions must be based on other types of information. In recent years, the techniques of managerial and cost accounting have been developed and refined to fulfill this informa-tional need. Linkages among these accounting systems and other critical components of the management planning and control process are illustrated in Exhibit 1. This discussion will focus on the decision support to be derived from cost accounting and managerial accounting procedures.

Exhibit 1. Accounting Systems Linkages

Cost Accounting

Cost accounting encompasses a body of concepts and techniques that support the objectives of both financial accounting and managerial accounting. It involves the assembly and recording of the elements of expense incurred to attain a purpose, to carry out an activity, operation, or program, to complete a unit of work or a project, or to do a specific job. Cost accounting systems can be found in both profit and non-profit organizations and in both product- and service-oriented entities. Cost allocation methods provide a means for accumulating and determining the necessary costs of the service or product. The expense of obtaining cost data, however, must be maintained at a reasonable level, and the allocation of costs should not go beyond the point of practical application for more efficient and effective operations.

Basic Concepts of Cost

Cost can be defined as a release of value required to accomplish some goal, objective, or purpose. [1] In the private sector, costs are incurred for the purposes of generating revenues in excess of the resources consumed. While this profit motive is not applicable to most public organizations, the test as to whether a cost is appropriate and reasonable is still the same: Did the commitment of resources advance the organization or program toward some agreed-upon goal or objective?

Five basic cost components are involved in any activity, operation, project, or program: (1) labor or personal services (salaries, wages, and related employee benefits); (2) contractual services (packages of services purchased from outside sources); (3) materials and supplies (consum-ables); (4) equipment expenses (sometimes categorized as fixed asset expenses); and (5) overhead. Various direct cost components, such as direct labor and materials, are classified as prime costs, whereas indirect labor and overhead are classified as conversion costs. In the private sector, overhead is defined as all costs, other than direct labor and materials, associated with the production process. Used in this context, overhead may involve variable costs (for example, power, supplies, contractual services, and most indirect labor) or fixed costs (for instance, supervisory salaries, property taxes, rent, insurance, and depreciation).

Decisions must be made in cost accounting as to the distribution of direct and indirect costs. A direct cost represents a cost incurred for a specific purpose that is uniquely associated with that purpose. The salary of the manager of a day care center, for example, would be considered a direct cost. The center might be divided into departments according to different age groups of children, with a part of the manager's salary allocated to each department. Then the manager's salary would be an indirect cost of each department. Indirect cost is a cost associated with more than one activity or program that cannot be traced directly to any of the individual activities. In the public sector, the terms indirect cost and overhead often are used interchangeably.

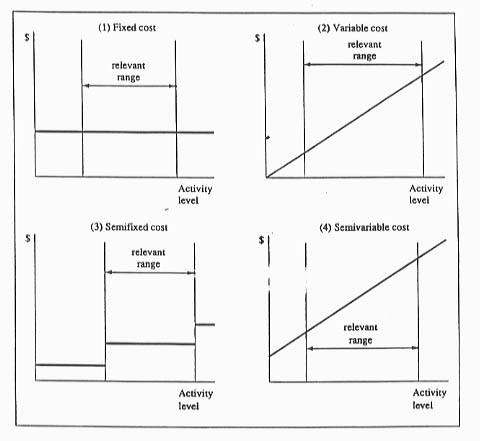

Costs can also be defined by how they change in relation to fluctua-tions in the quantity of some selected activity--for example, number of hours of labor required to complete some task, dollar volume of sales, number of orders processes, or some other index of volume (see Exhibit 2). Fixed costs do not change in total as the volume of activity increases, but become progressively smaller on a per unit basis. Variable costs are more or less uniform per unit, but their total fluctuates in direct proportion to the total volume of activity. Note that the variable or fixed character of a cost relates to its total dollar amount and not to its per unit amount.

The acquisition of equipment illustrates a fixed cost. As the volume of activity increases, the total cost of the equipment is spread over an increasing number of units. Therefore, the cost per unit becomes less and less. Personnel, on the other hand, illustrates variable costs. Each employee carrying out similar tasks is paid approximately the same amount. As the number of tasks increases, however, the number of employees must also increase (assuming that some level of productivity or efficiency is to be maintained).

Exhibit 2. Graphic Illustration of Cost Concepts

Costs may also be semi-fixed, described as a step-function, or semi-variable, whereby both fixed and variable components are included in the related costs. Salaries of supervisory personnel might be described as semi-fixed costs; at some level of increased activity, additional supervisory personnel may be required. Maintenance costs often exhibit the characteristics of semi-variable costs. A fixed level of cost is initially required, after which maintenance costs may increase with increases in the level of activity. Since costs are usually classified as either fixed or variable, the incremental character of these mixed categories often is a determining factor. If the increments between levels of change are large, the costs may be classified as fixed; if the increments are relatively small, the costs are usually defined as variable.

Measurement of Costs

A basic objective of cost accounting is to identify and measure costs incurred in achieving some program goal or objective. Several approaches to the measurement of costs may be relevant, however, depending on the informational needs of management.

Full costing, for example, attempts to delineate all costs properly associated with some operation or activity. In the governmental and nonprofit areas, full costs are often called program costs. Patient care costs, for instance, involve hospital room costs, meals, laundry, drugs, surgery, therapy, and other items that are more or less directly attribut-able to the patient. But what about admission and discharge costs, nursery care, or heat, light, and other utilities? Several problems may be encountered in considering all the fixed and variable costs associated with particular activities unless an accrual accounting system has been adopted to track these costs over several fiscal periods. [2]

One of the more controversial aspects of the full-costing approach is the method of assigning overhead or indirect costs to operating depart-ments. As noted, overhead includes the cost of various items that cannot conveniently be charged directly to those jobs or operations that are benefited. General administrative expenses are included in this concept of indirect costs. It can be argued, for example, that the cost of a personnel department, an accounting department, and other service or auxiliary units should be assigned in some fashion to the operating departments. By the same logic, utility costs, building maintenance costs, depreciation, and so forth can also be assigned to specific operating units. These indirect costs are often distributed (prorated) on a formula basis, as determined by labor hours, labor costs, or total direct costs of each job or operation. Other indirect costs have to be allocated arbitrarily because they cannot be traced directly to the individual organizational units.

Many indirect costs, however, are clearly beyond the control of the managers of operating departments. In recognition of this fact, responsibility costing assigns to an operating department only those costs that its managers can control, or at least influence. Many argue that this approach is the only proper measure of the financial stewardship of an operating manager. Responsibility costing will be discussed further in a subsequent section.

A useful approach to cost accounting is to consider only the variable or incremental costs of a particular operation. For example, a city manager might want to know how much it would cost to increase the frequency of trash collection from once to twice a week, or how much extra it would cost to keep the community's public swimming pools open evenings. The same type of questions might be raised by the management of any organization that delivers a service on some regularly scheduled basis. This approach, called direct costing, is relatively easy to associate with an organization's budget. Direct costing can be very helpful in making incremental commitments of resources.

Process costing is most often found in organizations characterized by the production of like units, which usually pass in continuous fashion through a series of uniform production steps called operations or processes. Costs are accumulated by departments (often identified by the operations or processes for which they are responsible), with attention focused on the total department costs for a given period in relation to the number of units processes. Average unit costs may be determined by dividing accumulated department costs by the quantities produced during the period.

Unit costs for various operations can then be multiplied by the number of units transferred to obtain total costs applicable to those units. Process costing creates relatively few accounting problems in those instances where this approach can be applied to various types of service organizations, including public agencies. This method cannot be used to determine cost differences in individual products or outputs, however. Unit costs often can be determined for many activities simply by dividing total program costs for a given period by the number of persons served (or tons of trash collected, number of inspections made, miles of road patrolled, or some other applicable measure of the volume of activity during some fiscal period). It is important to reduce unit costs to some measure that can be applied consistently over a variety of situations, however. Remember the eight grade algebra problem: "If a farmer and a half can plow a field and a half in a day and a half at a cost of $75, how much will it cost to plow 200 acres, assuming that the farmer's field is 10 acres?" First it is necessary to determine how much it costs to plow one acre. The farmer can plow a ten-acre field in one day at a cost of $50. Therefore, it costs $5 an acre, and to plow 200 acres would cost $1,000.

This classic problem illustrates one of the dilemmas frequently encountered in developing unit costs: Is it important to consider the number of persons required to carry out the task or deliver the service? If it takes two people three hours to paint a flag pole, should units costs be expressed in terms of both individuals? Or should the costs be translated into an hourly cost, since some flag poles may be higher than others and consequently, may take more hours to paint? This question has to be considered and carefully resolved for each situation for which unit costs are being developed. There are no hard-and-fast rules by which this determination can be made other than the logic of consistency.

In some public programs, unit costs are often determined simply by dividing the current budget allocation for a given activity by the number of performance units. If the annual budget of the welfare department is $2 million and the case load is 5,000, then the "unit cost" is $400 per case. This approach may produce rather misleading results, however. Important variables that may influence the cost of providing agency services may be masked by such an aggregate approach. Therefore, it may be necessary to further subdivide the case load into more detailed categories, e.g., by various client groups, by the relative ease (or difficulty) to deliver the requisite service, by the level of staff skills or other resources required to handle the cases, and so forth.

Budgetary appropriations may not always be a good measure of current expenses, since encumbrances for items not yet received may be included in such allocations. At the same time, expenditures to cover outstanding encumbrances from the preceding fiscal period may be excluded. Even if costs are limited to expenditures, current unit costs may be overstated if new capital equipment is included in the expenditures or if there is a large increase in inventories. Conversely, in many organiza-tions unit costs may be understated because of a failure to account for the drawing down of inventories or for depreciation (or user costs) of equipment.

Each activity should be examine in terms of the cost components that go to make up the total cost. In some cases, it may be appropriate to determine a unit cost for each component--personnel, materials and supplies, equipment, and so forth-- and then sum these costs in the appropriate mix to determine an aggregate unit cost for the particular activity or task.

Cost Allocation

Cost allocation is necessary whenever the full cost of a service or product must be determined. In particular, the variable, fixed, direct, and indirect components of cost must be considered in making cost allocations. Examples of this requirement in the public sector include the costing of governmental grants and contracts, the establishment of equitable public utility rates, the setting of user rates for internal services expected to operate on a "break-even" basis (that is, recover full costs), and the determination of fees (such as for inspections, processing of licenses and permits, use of public recreational facilities, and so forth).

Variable costs directly associated with a given service or activity usually do not present an allocation problem. As a rule, such costs can be measured and assigned to appropriate activities or programs that generate such expenses. As additional units of work are undertaken, variable costs usually increase in some predictable and measurable fashion.

A given organizational unit may also experience direct fixed costs (such as rent). The allocation of such costs to specific services or projects can be more problematic, however, since these direct costs do not vary with the activities being measured. They might be allocated by assuming some level of operation, such as number of persons to be served. To arrive at a unit rate, the total annual cost can then be divided by the estimated level of activity. In other instances, direct fixed costs may have to be allocated on the basis of some arbitrary physical measure, such as the floor space occupied by various activities. In either case, it is important that full accrued costs are allocated to avoid the problem of encumbrances.

In determining full unit costs, it is important to allocate to various departments or programs those costs identified as direct to the total organization. This represents a major cost allocation problem. The salaries of various administrative and support personnel in a hospital, for example, are direct costs to the hospital as a whole. When allocated to various separate departments or service functions--such as the intensive care unit, nursery, surgery, cafeteria, laboratories, and other components of the hospital--these administrative and support salaries become indirect costs to these operating units. Although often arbitrary, the basis for such allocations should be reasonable and should be based on services provided to these related units.

Overhead often is divided into two categories. Actual overhead costs that can be identified with a specific organizational unit typically are recorded by means of an overhead clearing account and some type of subsidiary record, such as a departmental expense analysis or overhead cost sheet. Allocated or applied overhead (indirect costs that cannot be traced directly to individual organizational units) is distributed through the use of predetermined rates.

One approach to the allocation of indirect costs involves the identi-fication of a number of indirect cost pools. Each pool represents the full costs associated with some specific administrative or support function (which cannot be allocated directly to individual projects or activities)--for example, operation and maintenance of the physical plant (including utility costs); central stores, motor pool, computing center, or other internal service units; general building and equipment usage; and central administration. Note that with internal service units, some costs often can be assigned directly as operating units draw upon these services. Indirect costs often represent the "fixed" costs of these service units (that is, the basic cost of having the services available).

Once these indirect cost pools have been identified, they can be arrayed from the most general to the most specific with regard to the particular programs or activities for which indirect cost rates are to be established. Costs from the more general pools are allocated (or stepped down) to the more specific pools and, finally, to the primary functions or activities of the organization. An indirect cost rate is then determined by dividing the total direct costs associated with a given program or activity into the total indirect costs allocated to that function. It is possible through this method to determine the impact of changes in these indirect costs on the full costs of individual programs, projects, or activities.

Under- or over-application of indirect costs may develop when predetermined rates are used, and significant differences may arise from month to month. However, if the cost allocation methods have produced reliable estimates, these accumulated differences should become rela-tively insignificant by the end of the fiscal year.

Posting to Cost Accounts

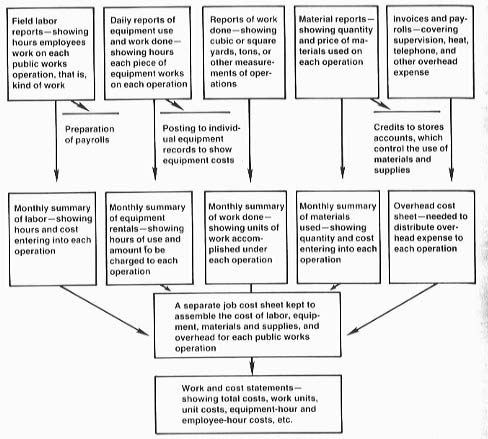

Procedural steps for summarizing and posting data to cost accounts are outlined in Exhibit 3. Field reports provide the primary record of work performed and expenses. The particular design and maintenance of such reports often depends on local circumstances. A job ordering system may be installed, for example, to monitor and record street maintenance costs. A crew foreman or project supervisor may prepare the field report. Or it may be desirable to have each employee prepare a daily or weekly "time and effort report," indicating specific work assignments and the time spent on each operation. Separate bills of materials used and statements of equipment used for each job or operation would have to be provided by supervisory personnel. Field reports should be summarized before posting to job cost sheets or work and cost ledgers. The information gathered through these field reports can serve several purposes. Reports used to determine the cost of labor entering into each operation or job can also provide a basis for payroll preparation (a general accounting function). Daily reports by equipment operators provide summaries of the pro-rated costs (equipment rental charges) to be distributed to the various jobs on the cost ledger. These reports can also be used to post individual equipment records (showing, for each piece of equipment, the expenses for labor, gasoline, oil, and other supplies, repair costs, overhead, and depreciation). Materials and supplies reports indicate stores withdrawn from stockrooms, providing credit to stores accounts as well as charges to operating costs accounts.

Exhibit 3. Posting Data to Cost Accounts

Many indirect costs can be reported in substantially the same manner as direct costs--from time reports, store records, and so forth. Certain indirect costs can also be determined from invoices on such items as travel expenses, utility services, and general office expenses. These indirect costs are initially posted to an overhead cost sheet and then allocated to jobs and activities on some predetermined basis.

The job cost sheet is the final assemblage of the information with respect to all work performed and all costs incurred. Accounts in the work and cost ledger are generally posted monthly and closed upon completion of a specific job or at the end of the regular accounting period, when unit costs on an activity or program are recorded.

Monthly summary statements of work completed, expenses, units costs, and employee-hour production can be compiled readily from information on the job cost sheets. Other statements may be prepared periodically, according to the needs of management, on such subjects as total labor costs, employee productivity, equipment rental costs, noneffective time and idle equipment, and loss of supplies through waste or spoilage.

Standard Costs and Variance Analysis

Standard costs relate the cost of production to some predetermined indices of operational efficiency. If actual costs vary from these standards, management must determine the reasons for the deviation and whether the costs are controllable or noncontrollable with respect to the responsible unit. Misdirected efforts, inadequate equipment, defective materials, or any one of a number of other factors can be identified and eliminated through a standard cost system. In short, standard costs provide a means of cost control through the application of methods of variance analysis.

Standard cost systems have been widely used in the private sector, but have been relatively limited in their government and other not-for-profit applications. Nevertheless, such standards have relevance in a number of organizational environments.

In setting up standards, optimal or desired (planned) unit costs and related workload measures are established for each job or activity. Work-load measures usually focus on time-and-effort indices, such as number of persons served per hour, yards of dirt moved per day, or more generally, volume of activity per unit of time. After these measures have been established, total variances can be determined by comparing actual results with planned performance. Price, rate, or spending variances should then be determined for differences between standard and actual costs. Quantity or efficiency variances can be developed for measured differences between the anticipated and actual volume of activity. Knowledge of differences in terms of cost (price) and volume (efficiency) enables the manager to identify more clearly the cause and responsibility for significant deviations from planned performance.

If, for example, the anticipated volume of a city bus system is 600,000 riders at a fare of $0.50, but only 525,000 riders actually use the service, the bus system's volume variance is $37,500 (75,000 riders times $0.50). If the actual fare charged is $0.55 instead of $0.50, the total variance is only $11,250 [(600,000 x $0.50) - (525,000 x $0.55). The volume variance is still $37,500. However, there is a favorable price variance of $26,250 [(525,000 x $0.55) - (525,000 x $0.50). A mix variance would result if different routes call for different fares, and the actual mix of routes is different from the mix anticipated (and budgeted).

There are no hard-and-fast methods for establishing cost standards. However, workload and unit cost data from prior years serve as a logical starting point. More detailed studies may be required to determine the quantity and cost of personal services, materials, equipment, and indirect costs associated with particular kinds of effort or volumes of activity. Unit costs can be estimated for each cost element by adjusting trend data for expected changes during the next fiscal period. Standards should be established for each cost element entering into a given job or operation. These standards can be combined to establish an overall cost standard for the particular type of work, activity category, or program element.

Standard costs should be systematically reviewed and revised when found to be out of line with prevailing cost conditions. Changes in these standards may be required when new methods are introduced, policies are changed, wage rates or material costs increase, or significant changes occur in the efficiency of operations. Furthermore, standard costs are "local" in their application. Such standards often differ from organization to organization, reflecting different labor conditions, wage rates, service delivery problems, and operation methods. It may be inappropriate, for example, to evaluate regional offices of a state health department using a single standard cost for delivery of key services. Program costs in more rural areas may be higher because of transportation distances, or may be higher in urban areas because of "hard-to-reach" cases.