Financial

Planning and Management in Public Organizations by Alan Walter Steiss

and Chukwuemeka O'C Nwagwu

Financial

Planning and Management in Public Organizations by Alan Walter Steiss

and Chukwuemeka O'C Nwagwu Financial

Planning and Management in Public Organizations by Alan Walter Steiss

and Chukwuemeka O'C Nwagwu

Financial

Planning and Management in Public Organizations by Alan Walter Steiss

and Chukwuemeka O'C Nwagwu

INVESTMENT STRATEGIES

Until a few years ago, cash management was viewed as one of the more mundane task carried out by financial officers. Government leaders rarely played a role in cash management decisions, and many delegated the entire decision-making process. Circumstances have changed, however. The recent financial crisis in Orange County, California has stimulated new interest among high level public officials and politicians alike. New legislation has been passed in several states that limits the discretionary authority of fund managers. Other states are considering such legislation. The environment in which fund managers work is likely to continue to evolve over the next several years as a result of this new conservatism.

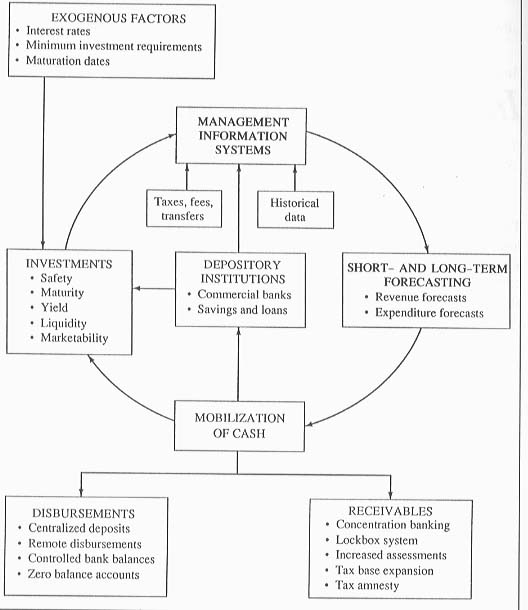

Cash Management Model

The purpose of cash management is to maintain sufficient liquid assets to satisfy legal obligations, while at the same time, utilizing unrestricted funds to generate income. This chapter will focus on providing the reader with the background knowledge necessary to apply improved forecasting and cash mobilization techniques in the development of sound investment strategies. These strategies will focus on maximizing investment potential while at the same time, maintaining the safety of investment funds. While investment is speculative vehicles may be appropriate for certain individual investors, it has no place when investing public funds., Such risky investing of public funds can have disastrous results, as we have learned from recent experiences in California and other states.

Central to the cash management model is an information management system that provides data and analyses regarding available fiscal resources, such as taxes, fees, and intergovernmental transfers, as well as historical data and other information necessary to develop short and long-term forecasts of revenues and expenditures. Information flows from banks and other financial institutions to the information management system (IMS). This information is used to maintain the fiscal system on its present course or to modify it. Information generated at each level of the model feeds into and facilitates the achievement of objectives at the next level. In this way, a cycle is created, proceeding from the information management system to forecasting, cash mobilization, banking, investments, and back to the IMS. With appropriate cash management, the cycle is continuously repeated.

Mobilizing Cash for Investments

Investment income can be increased if income can be obtained sooner and held longer. As discussed in the previous chapter, the receipt of expected revenues can be accelerated by using such available technologies as lockbox systems and area concentration banking. Other sources of revenue can be exploited by improving property tax assessments, expanding the tax base, and minimizing delinquent taxes (for example, by levying penalties and/or granting a tax amnesty). The productivity of available cash can also be maximized by controlling disbursements through the use of such techniques as centralized deposits, zero balance accounts, controlled bank balances, and remote disbursements (writing checks on remotely located banks).

Receivables are deposited in banks and other financial institutions for safekeeping and/or investment. Localities may authorize banks to invest amounts in excess of operating requirements, or cash managers or investment brokers can be hired to manage their investments.

Local governments accumulate cash balances for a number of reasons. A large inflow of revenue occurs, for example, immediately prior to penalty dates on the tax calendar. Intergovernmental transfers tend to be made in lump-sums as a consequence of statutory regulations and administrative practices governing such payments. Bonds for capital improvements usually are issued before a project begins, whereas disbursements of these funds occurs only as bills are paid throughout the construction period.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Exhibit 1. Cash Management Model

_________________________________________________________________________________________

As a consequence of these and other factors, a jurisdiction often is able to meet its current obligations and, at the same time, have some non-committed cash left over to invest in interest yielding securities.

Investment of idle funds is one of the tools of sound fiscal management being used more frequently by all levels of government. . . . It offers a source of additional revenue without increasing taxation, through the use of funds which would otherwise be temporarily unproductive. [1]

Upward trends in interest rates in recent years have been a contributing factor to the increased interest among local governments in the investment of idle cash balances.

Public Investment Criteria

The principal criteria to be considered in selecting a specific security in which to invest public funds are: (1) safety/risk, (2) price stability, (3) liquidity/marketability, (4) maturity, and (5) yield. It has been said that the ideal investment is one that yields a high return at no risk, offers promise of substantial growth, and is instantly convertible into cash if money is needed for other purposes. This ideal specimen, of course, does not exist in reality. Each form of investment has its own special virtues and shortcomings. In general, securities with little risk, high liquidity, and short maturities also have low yields. For an investment to provide a high yield, one or more of the other relevant criteria must be compromised.

Safety/Risk

It has long been assumed that public officials generally follow a fairly conservative path when investing public funds and that safety is accorded the highest priority. Over the past several years, however, it has become evident that a significant number of fund managers are routinely committing public funds to relatively risky investments. Although some of these fund managers have produced enviable returns on investments, others have lost large sums of public money. In a few cases, the outcome has been devastating.

However, the vast majority of local governments tend to invest in securities with relatively low levels of risk--and subsequently, low rates of returns. Public treasurers often take this more conservative approach because they are concerned that may find their positions in jeopardy if a portion of these public funds is lost as a consequence of risky investment practices. Many localities, however, have a financial base that is large enough and strong enough to take limited risks without serious fiscal damage. An investment in a higher-yielding security may be appropriate if the risk is only slightly higher.

Many state legislatures restrict the investments of local governments to securities that are collateralized or backed by the United States government. Even these investments--for example, long-term government bonds--"fluctuate in value and thus present some risk if they must be sold prior to maturity in an unfavorable market." [2] The risk characteristics of different securities should be understood before decisions are made about which specific instrument to purchase (see Exhibit 2).

Price Stability

Investments constitute cash reserves in addition to serving as income-producing assets. In the event of an unexpected cash shortage, the first reaction often is to convert some financial assets into cash. The desire to avoid financial loss under such circumstances explains the concern of public officials for the price stability of investments.

Generally speaking, U.S. Treasury bills (T-bills) are the most stable of all money market instruments, principally because they are backed by the full faith and credit of the federal government. In addition, T-bills are usually issued on a short-term basis, maturing before new market conditions alter the assumptions on which the investment strategy was based. Other investment instruments characterized by price stability are short-term obligations of the U.S. Treasury, federal agency issues, and certificates of deposit.

Liquidity/Marketability

The concept of liquidity involves managing investments so that cash will be available when needed. The basic question is: Can a security be sold quickly and easily when the need arises? Marketability varies among money market instruments, depending not only on the price stability of the instrument, but more importantly, on the extent of the secondary trading market available to it. Treasury bills, for example, are practically riskless and are actively traded. As Harrell and Cole observe, "the sheer volume of Treasury bill issues and their tradeability in the secondary market establish the bills as the nearest equivalent to pure cash in the market." [3] Federal agency issues and certificates of deposit also have excellent liquidity.

| Investment Instrument | Obligation Issuer | Denomina. | Maturities | Market | Yield Basis | Comments/ Restrictions |

| United States Treasury Bills | U.S. Government obligations | $10,000 to $1 million | 3, 6, 9 & 12 months | Execellent secondary market | Discounted on 385-day basis. Also offered as tax anticipation bills through special actions | Popular investment; can be purchased in secondary market for varying maturities |

| U. S. Agency Securities | Various Federal Agencies | $1,000 to $25,000 | 30 days; 270 days; one year | Good secondary market | Discounted on a 360-day basis | Not legal obligtation of or guaranteed by the Federal Government |

| Negotiable CDs | Commercial Banks | $500,000 to $1 million | Unlimited; 30-day minimum | Active secondary market | Interest maturity on 360-day basis | Backed by credit of issuing bank |

| Non-Negotiable CDs | Commercial Banks/ Savings & Loan Associations | $1,000 minimum (usually $100.000) | 30-day minimum | Limited secondary market | Interest maturity on 365-day basis | Lower interest rates for amounts under $100,000; 90-day interest penalty for early withdrawal |

| Repurchase Agreements | Commercial Banks | $100,000 minimum | Overnight minimum; 1 to 21 days common | No secondary market | Established as part of purchase Yield generally close to prevailing federal rates | Open: can be liquidated at any time. Fixed: maturity set for specific period |

| Banker's Acceptances | Commercial Banks | $25,000 to $1 million | Up to six months | Good secondary market | Discounted on a 360-day basis | Backed by credit of issuing bank with specific collateral |

| Commercial Paper | Promissory Notes of Finance Companies | $100,000 to $5 million | 5 to 270 days | No secondary market | Either discounted or interest-bearing on a 360-day basis | Dealers will often negotiate "buy-back" agreements at a lowerf rate prior to maturity |

Maturity

One way around the liquidity problem is to time the placement of investments so that they mature when the locality expects to need cash. Part of the investment portfolio may be earmarked for capital projects, and part of anticipated operating expenses. In managing the portfolio, the maturity dates of holdings should be synchronized with the dates when these funds will be needed, It should be relatively easy to align these dates, because securities are usually classified according to their maturity periods, such as 30 days, 60 days, 90 days, one year, or five years.

The sale or redemption of a security prior to the agreed upon maturity date usually results, at the very least, in the loss of accrued interest. This predicament can be avoided by buying a mix of securities with scattered maturity dates. In this way, any time cash is needed, some asset is maturing, and losses from premature sales can be avoided.

Yield/Return on Investment

Yield is the ultimate measure of successful fiscal management in a market economy. Yield is defined as the internal rate of return of a security's cash flows. It is the discount rate which equates a bond's invoice price (that is, principal plus accrued interest) with the present value of its coupon and principal payments. The yield for a bond with a 4% coupon rate and an invoice price of $1,021.27, maturing five years after the issue is 3.5 percent. In other words, an investor would have to pay the underwriter $21.27 over par value to cover the premium and accrued interest). Over the five-year period to maturity, the investor would earn $200 in interest (4% per year for five years) and at maturity, would receive $1,000 in principal. The net return on the investment is $175.73, which is the equivalent of a 3.5% return over five years on the invoice price of $1,021.27.

The yield on an investment is conditioned by several exogenous factors, including interest rates, minimum investment requirements, and the maturity dates of investments. In general, the longer the maturity of an investment, the higher the yield. For this reason, it is important to design an investment pattern whereby each security will mature close to the time that the money invested will be needed to cover operational needs.

In spite of the constraints imposed by safety and liquidity, local governments are becoming increasingly interested in yield. As a first step, many financial executives have increased their efforts to monitor account balances to ensure that excess cash is invested immediately. In addition, some localities are backing away from state and local government obligations, which characteristically have low yields, in favor of high-yield, high-grade corporate bonds. At the same time, however, many local officials still rank yield as the least important of all the criteria in selecting an investment instrument.

Types of Securities

Understanding the unique features of each type of the security available to local governments is critical to the formulation of prudent investment strategies. The money market instruments most widely used by local governments are arrayed in Exhibit 2 against the characteristics described above.

Local governments and other public organizations often hold short-term securities that can be readily converted into cash either through the market or through maturity. The most attractive instruments that meet these criteria are federal securities, which are practically riskless, since they are backed by the full faith and credit of the federal government. Other securities carry varying degrees of risk and, therefore, must offer higher interest to make them attractive. Relatively risk-free securities include: time deposits, certificates of deposit, commercial paper, banker's acceptances, and repurchase agreements.

The majority of states allow municipalities to use a variety of investment instruments, including U.S. Treasury bills, Treasury notes, commercial bank certificates of deposit (CDs), savings and loan deposits, federal agency securities, and repurchase agreements. However, the majority of states also prohibit local governments from investing in banker's acceptances and commercial paper (which generally earn higher rates of return than the approved securities).

Treasury Bills, Notes, and Bonds

U.S. Treasury bills (T-bills)--the most important money market instrument available for local government investment--represent an obligation of the United States government to pay a fixed sum of money after a specified period of time from date of issue. T-bills are negotiable, non-interest-bearing securities that have virtually no default risk and are the most liquid of money market instruments. The Treasury auctions three-month (13 weeks) and six-month bills (26 weeks) on a weekly basis (Mondays) and one-year bills each month.

T-bills are issued at a discount and then mature at par value. The amount of the discount varies at the time of issuance. The difference between the selling price and the face value represents interest income. The minimum denomination is $10,000, with additional amounts in increments of $5,000. The price of Treasury and other federal agency securities are quoted in 32nds and halves of a 32nd. For example, a price of 93-12 is 93 and 12/32nds percent. If the par value of the security is $10,000, then the price would be $9,337.50 (i.e., $10,000 times 93.375). The investor would receive $10,000 at maturity. If the security is a one-year T-bill, the yield would be ($10,000 - $9,337.50) divided by $9,337.50 = 7.095%.

T-bills are sold either by competitive bid or non-competitive tender. A noncompetitive tender simply states the number of T-bills the buyer desires, which will be awarded at the average price of the competitive bids accepted. The Treasury determines the number of bills it wishes to sell before the bidding begins, and the noncompetitive tenders are allocated first, with the remaining bills awarded to the competitive bidders, highest price (lowest discount yield) bids first.

The buyer of a T-bill does not receive a certificate. Ownership is recorded on the computer at the buyer's clearing bank and, in turn, on the computers at the Federal Reserve System. This book entry system permits the daily trading of billions of dollars of T-bills without the shifting of countless pieces of paper to record the transactions. Each owner gets periodic statements from the bank, acting as custodian, regarding the bills owned.

Treasury securities can be purchased with no commission cost through a program called Treasury Direct or through a broker (at a cost of $50 to $60 per transaction). The Treasury Direct program is designed for the investor who intends to hold the securities until they mature and requires that the interest and principal payments from Treasury securities be deposited directly into a checking or savings account. Therefore, investors who want to actively trade Treasury securities must buy them through a broker.

T-bills have virtually no default risk and are the most liquid of money market instruments. An attractive feature of T-bills is the ready market for resale. T-bills are traded at a "discount yield," which determines the size of the discount and the price of the bill. If the holder has a sudden need for funds, T-bills can be sold quickly for relatively predictable prices on the so-called secondary market. This characteristic has earned T-bills the label of "near money."

U.S. Treasury notes are intermediate term obligations, issued in two-year, three-year, five-year, and ten-year maturities. Treasury bonds are long-term obligations, issued in maturities from ten to thirty years. Treasury notes and bonds are interest-bearing, negotiable securities, with coupon interest paid semi-annually. When originally issued, notes with two- or three-year maturities are available in $1,000 increments, with a minimum purchase of $5,000. Treasury bonds, notes, and bills are backed by the full faith and credit of the federal government and are prime obligations with an implied AAA rating.

The Treasury issues notes in regular cycles, like T-bills, but much less frequently (monthly for two- and five-year notes, quarterly for ten-year notes). Both competitive bids and noncompetitive tenders may be made for notes. All notes are noncallable by the Treasury. T-bonds are auctioned semi-annually (usually in February and August) through a process similar to that used for notes. Some T-bonds have a call feature; they may be called by the Treasury at par five years before the maturity date.

In normal financial markets, the yield on long-term bonds is greater than on short-term instruments, such as T-bills and money market funds. In today's market, however, the gap between short-term and long-term rates is not great. In October, 1998, for example, the yield earned on 10-year Treasury notes dropped to 4.16%, according to the Federal Reserve Board. The last time the yield was this low was in December, 1964. Interest rates fall because the money available to lend is greater than the demand for money to be borrowed. Interest rates also tend to follow inflation, and the current rate of inflation in the United States is very low. Many economists believe that any further decline in interest rates will most likely be in short-term instruments.

Zero Coupon Treasury Securities

Zero Coupon Treasury securities represent ownership of interest or principal payments on United States notes or bonds. Instead of periodic interest payments, these securities are purchased at a discount of 20% to 90% off the $1,000 face value. Owners of Zero Coupon Treasuries receive no payment of interest until maturity. These securities are available in a wide range of maturities spanning one to thirty years, and major security dealers maintain an active secondary trading market. The best known zero coupon security is a United States Savings Bond.

The most popularity type of Zero Coupon Treasury securities are STRIPS (Separate Trading of Registered Interest and Principal Securities), introduced in 1986 to meet the needs of investors for ready access to the zero coupon securities. The Treasury does not issue STRIPS. Instead, the Treasury declares that certain issues of Treasury notes and bonds are eligible to be split into separate interest and principal payments, with each payment tradiung as a separate security. This splitting up, or "stripping," of the issue, is done by government bond dealers and others, and not by the Treasury. Investors in STRIPS do not receive a physical certificate to serve as proof of ownership. Rather STRIPS are registered in the name of the holder and are held in "book entry" form through the wire system of the Federal Reserve, facilitating the trading and liquidation of these securities by the holders. If sold before maturity, the market price will depend on the prevailing levels of interest rates.

Interest earnings from zero coupon securities are automatically reinvested at the same yield basis at which the investor originally bought the bond. This guaranteed compounding feature is attractive enough that investors are willing to pay higher prices (lower yields) for zero coupon securities than for regular coupon bonds.

Older zero coupon securities exist, but none have been issued the Treasury since the mid-1980s, due to the STIPS program. CATS (Certificates of Accrual on Treasury Securities) were the most widely traded "physical" Zero Coupon Treasury security, with over $45 billion (face value) of CATS created. Treasury Investment Growth Receipts (TIGRS) were frequently purchased to provide a college education fund with a minimal initial investment. As a gift, TIGRS offered a tax-advantage to both parents and to a child (with a custodial account).

Certificates of Deposit

Certificates of deposit (CDs) are issued by commercial banks and thirft institutions and represent funds deposited for specified period to earn fixed rates of interest. Upon deposit of funds, the investor receives a certificate specifying the terms of the investment, including the interest rate, compounding interval, and date of maturity. The owner of the CD receives both principal and interest on the maturity date. CDs are sold according to specified maturity periods, ranging from seven days to five years. As with other investment instruments, the longer terms often pay significant higher interest rates. Many banks use the term CD for savings certificates issued in relatively modest amounts. The advantage of a CD over a standard savings account is that the interest rates generally are higher. However, as a general rule, these more modest CDs can be transferred only with considerable difficulty (if at all).

Money market CDs are negotiable instruments, issued in minimum denominations of $100,000 or more. There are two types of CDs: (1) negotiable, which the original investor can sell to another party on the secondary market; and (2) non-negotiable, which must be retained by the original investor until maturity. The ability to sell prior to maturity if the funds are needed gives CDs the liquidity necessary to make them competitive in the money market and therefore, makes them attractive to investors. Emergency liquidation of a CD prior to maturity can result in a loss of interest, however. Although a CD may have been purchased for only thirty or sixty days, in some cases a bank may require a penalty of ninety days' interest for early withdrawal.

Public organizations should invest only in those CDs which are insured by the FDIC. Not all CDs are federally insured, and some vendors may not volunteer this information. Private companies sometimes issue what they call "certificates". However, these are backed only by the private companies issuing them.

Banks have recently begun to issue callable CDs which at the option of the issuer may be redeemed at par prior to the original stated maturity. The issuer pays the investor a higher interest rate in exchange for this call feature. The CDs have a time period, usually one or two years from the issue date, during which they are non-callable, at the end of which they may be called for the maturity value of the original investment. When interest rates are declining, the probability of the investment being called increases significantly.

Federal Agency Securities

Federal agency securities are excellent investment instruments for local governments and are often characterized as close substitutes for Treasury bills. These securities are issued by government-sponsored, privately-owned agencies that have been established to implement various federal policies and include the Federal Farm Credit Bank System, Farm Credit Financial Assistance Corporation, Federal Home Loan Bank System, National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae), Student Loan Marketing Association (Sallie Mae), and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac). . The Mortgage-backed securities pay interest rates about 1.5 percentage points higher than Treasury bonds. Most agencies have minimum denominations of $10,000 with additional increments of $5,000. The Financing Corporation and the Resolution Trust Company were set up by Congress in the late 1980s to deal with problems caused by the failure of savings and loan institutions with resulting difficulties for the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation.

Agency securities are traded in an over-the-counter market, similar to U.S. Treasury obligations and usually by the same dealers. However, the spreads are somewhat wider, and therefore, it is more costly to trade in this market than in the Treasury market. Investors can choose from discounted notes, interest-bearing notes and bonds, and floating-rate notes. Although these securities are not backed by the full faith and credit of the federal government, each agency guarantees its own issued securities. Thus, the risk factor is considered to be very low. These agency securities have less liquidity, however, because the market for agency paper is smaller than for T-bills and T-bonds. While agency securities trade at a yield premium over T-bills, the interest earnings are subject to federal income tax, and some agency securities are subject to state and local taxes.

Repurchase Agreements

A repurchase agreement is a contract between two parties whereby one party (e.g., a bank, perhaps acting as an agent for another party) sells an instrument (such as a T-bill) to another party (e.g., a municipality) and agrees to buy it back at a later date (often the next day) at a specified higher price. Repurchase agreements are most often entered into for very short periods of time, usually from one to twenty-one days. They often represent investment transaction where the original holder of the instrument requires capital to cover short-term obligations. In economic terms, the buyer of the repurchase agreement is lending money to the seller, on a short-term basis, and the loan, in effect, has been repaid when the seller repurchases the securities.

The minimum amount is usually $100,000, with increments of $5,000 above the minimum. Lower minimum can sometimes be negotiated, however. Two types of repurchase agreements are available: (1) fixed, wherein a specific interest rate and maturity period for the amount invested are established at the outset and if the agreement is liquidated prior to maturity, a penalty might be levied; and (2) open, meaning that the agreement may be liquidated at any time, with the interest rate--which may be slightly lower than for a fixed agreement--dependent on the duration of the transaction. A fixed repurchase agreement might be set for $100,000, with a 12.5 percent annual interest rate for six days. If the agreement is liquidated prior to maturity, the bank has the option of levying a penalty.

Repurchase agreements are the most flexible investment instruments available because they allow a locality to negotiate both yield and maturity. Little risk is involved in such agreements because the principal is guaranteed and the return is fixed. However, no secondary market exists for repurchase agreements. They can be used most effectively to invest unexpected windfall revenues on a very short-term basis while alternative investments are being considered.

Banker's Acceptances

Banker's acceptances are time drafts or letters of credit negotiated by commercial banks to finance the export, import, shipment, storage of goods, or other foreign trade transactions. [4] These notes do not bear interest, but are sold at a discount. The bank guarantees to honor the full face value of the draft of a private company on the due date (typically ninety days after issue) by stamping "accepted" on the draft. In making such a guarantee, a well-known bank can significantly enhance the marketability of obligations of less well-known companies. Both the issuer and the accepting bank guarantee the draft.

An export-import company, for example, may require $50,000 as a down payment on a foreign shipment of goods. The company might arrange for an American bank to issue, in the name of the exporter, an irrevocable letter of credit, which specifies the details of the shipment. The exporter can then draw a draft on the American bank and present it to an overseas bank for immediate payment. The draft is returned to the bank that issued the letter of credit which stamps it "accepted," thereby incurring the liability to pay the draft when it matures. The export-import company is obligated to deposit the $50,000 plus a specified interest in time to honor the acceptance at maturity. Alternatively, the bank may accept a time draft from the company for $50,750, repayable in 21 days. An investor provides the $50,000, and at the end of the 21 days, the account of the export-import company is charged $50,750, the investor is paid $50,600, and the bank retains $150 as its "placement fee." The $600 return on $50,000 is the equivalent of a 20.5% annual return on investment.

Banker's acceptances are sold in denominations ranging from $25,000 to $1 million. Major investors include the accepting banks, foreign central banks, money market funds, corporations, and other domestic and foreign institutional investors. The risk of default is very low, and dealers in the secondary market create sufficient liquidity for these instruments to continually attract investors. There are no known cases of principal loss to investors in the more than 70 years that banker's acceptances have been used in the United States.

Commercial Paper

Commercial paper is an unsecured promissory note issued for a specific amount with a matrurity ranging from three to 270 days. Most issues have an average maturity of 30 to 60 days. Commercial paper often is issued by corporations with short-term capital needs, finance companies, bank holding companies, municipal authorities, and more recently, foreign corporations and sovereigns. Automobile finance companies, such as General Motors Acceptance Corporation, are among the largest issuers. Commercial paper typically is sold in large denominations (in multiples of $100,000) as a discounted security; that is, the issues are purchased for an amount below their face value and then are paid back at full face value upon maturity. The difference between the face value and the purchase price represents the yield earned on the investment. Commercial paper is usually bought by large institutions, rarely by individual investors.

The rates offered on commercial paper depend on several factors: the credit rating of the issuer, the paper's maturity, the total amount of money sought by the issuer, and the general level of interest rates. Almost all commercial paper is rated by one of the major rating agencies to provide an indication of the credit risk involved with each issue. Commercial paper offers higher yields than T-bills or other short-term investment options of similar maturities to compensate investors for the higher risk.. No secondary trading market exists for commercial paper, and consequently, liquidity is generally low--investors usually must hold the paper until maturity.

At maturity, the commercial paper can be paid off or rolled over into a new commercial paper issue at the prevailing market interest rate. A remarketing agent is responsible for finding new investors if existing investors decide not to reinvest in the paper. Commercial paper typically is backed by a bank letter of credit or some other type of liquidity provision. If new investors cannot be found and if the issuer is unable to provide the funds to pay-off the existing investors, then the issuer may draw on the letter of credit in order to obtain the necessary funds. As a result of the higher default risks, many states have restrictions against investment by local governments in commercial paper.

The relative ease of issuance of commercial paper results in greater flexibility and the ability to match the amount and timing of funds with the issuer's needs. However, rising interest rates may negate the advantage of short-term paper. The use of commercial paper may be precluded by disruptions in the capital market. The costs of remarketing and obtaining a bank letter of credit or another type of liquidity provision offset some of the interest rate savings normally associated with commercial paper.

Local governments use tax-exempt commercial paper (TXCP) to meet cash management needs, to finance equipment, to provide interim construction financing for capital projects, and to provide loans to business entities. Issuing short term paper at tax-exempt interest rates allows for the possibility of positive arbitrage. The issuing jurisdiction eventually may sell long-term bonds to repay the TXCP, but in the interim, long-term reserve investments continue to earn interest. Tax-exempt commercial paper usually offers more flexibility than the issue of notes (BANs, TANs, RANs).

Money Market Funds

Money market funds may be considered as an alternative to a savings account. The administrator of the money market fund pools the funds of hundreds or even thousands of investors to give each investor interest rates that otherwise may not be possible. Investments made in the amount of $250,000 and up generally command higher interest rates than do lesser amounts.

Money market accounts often are set up to serve as a combination savings/checking account. Checks can be written on deposited funds. Money market funds are completely liquid, since they may be withdrawn at any time without penalty. Many banks offer a number of "perks" along with money market accounts. Tax free accounts may also be available for municipal funds.

All of the securities described above are excellent, safe investment alternatives for local jurisdictions. The specific yield-liquidity-safety configurations of each should be considered when making investment decisions. A locality usually purchases a mix of investments with varying yield-liquidity-safety arrangements, depending on which considerations public officials wish to emphasize in the overall investment program.

Stocks

Historically, the stock market has proven to be an excellent long-term investment option. However, short-term performance is virtually impossible to predict. Given that fact, direct purchase of stocks is generally not recommended for short-term investments of public funds. If a fund manager feels inclined to invest in stocks, he or she should do so through a mutual fund or index fund with a proven track record.

Index Funds

Index funds were originally introduced as an investment strategy for institutional pension funds. In 1976, Vanguard offered an index fund to individual investors. The goal of an index fund is to match the performance of some benchmark that it is tracking, such as the Standard & Poor 500, Dow 30, or Wilshire 5000. The concept of an index is based on the Efficient Market Theory which asserts that stocks and bond markets are efficiently priced at any given time and that an average investor could not beat the stock market on the whole. In fact, over long periods of time, only a small percentage of actively managed funds have beaten the market. So if you can't beat 'em, join 'em.

A pure index fund invests in every stock in the benchmark index it is tracking. A quasi-index fund tries to outperform the benchmark by using options or futures. Several mutual fund companies carry index funds--to name a few, Vanguard, Dreyfus, Fidelity, and Bull & Bear. Index funds have lower portfolio turnover and minimal research requirements and hence lower costs than actively managed funds. Although index funds offer more predictable results, they are fully vested at all times, and if the market declines, so will the fund.

Exchange-traded funds are also available to track the Standard & Poor 500 index, as well as other important domestic and international indexes. The most prominent of these exchange-traded index investments is the Spider, or SPDR, which is short for Standard & Poor's Depositary Receipt. The SPDR is similar to the closed-end funds, but it is actually called a unit investment trust or UIT. One SPDR unit is valued at approximately one tenth (1/10) of the value of the S&P 500. As a result, SPDRs can be expected to move up or down in value with the S&P 500 Index. Dividends are paid quarterly, based on the accumulated stock dividends held in the trust, less any expenses of the trust.

SPDRs can be bought or sold anytime during the trading day, and they can be shorted. When entering a short trade for a stock, the trade just before the short trade must be at a higher price than the previous trade--called an "uptick". The uptick rule does not apply to SPDRs.

Investing overseas is more difficult than investing domestically. Accounting and reporting rules differ from those in the United States, and it is not an easy task to paint an accurate picture of a country or an individual company. Therefore, when investing overseas, it often makes sense to use professionally managed investments. The World Equity Benchmark Series (WEBS) are similar to SPDRs. WEBS trade on the American Stock Exchange and track the Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) country indexes. WEBS are available for the following countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Italy, Japan, Malaysia Free, Mexico, Netherlands, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom

Derivatives

Derivative securities have received considerable coverage in the media in recent months, largely stemming from the decision of some local governments to seek bankruptcy court protection largely as a result of the these investments. Derivative securities derive their value from some form of investment, such as Treasury bonds, corporate stocks and bonds, foreign currencies, or commodities contracts. In essence they are bets that future interest rates will move in a particular direction. Derivatives were originally created to act as a safety device against dramatic changes in interest rates. When used in this manner, they are relatively safe. However, investment bankers have concocted a broad range of derivatives, often customized to suit the needs of their clients. When used as a speculative investment vehicle, the risk becomes great.

The simplest type of derivatives are futures--contracts that set a price today but specify acceptance or delivery some months hence. A sausage maker might buy hog futures to protect against price increases, whereas a meat packer would sell such futures to ensure against losses if the price goes down. A speculator might either buy or sell in the hope that a change will allow him/her to make money by reversing the transaction tomorrow.

Since every order to sell must be matched by an order to buy, derivative markets as a whole balance out to zero--as opposed to stock markets, where companies may issue shares regardless of whether there are buyers. The price of futures is constrained by the current cost of the underlying commodity. Otherwise, if the price of gold futures, say, rose above a certain point, speculators could profit by buying gold today and holding it for sale on the delivery date.

Another form of derivatives are options which confer the right to buy or sell stock (or other types of securities) at a fixed price for some period. Options are bets on the stock's future price, and the cost of the option is the ante for getting into the game.

Derivatives are designed to help corporations guard against sudden shifts in global financial markets--a plunging yen, a jolt in French bonds, a rapid rise in Hong Kong stocks, etc. One of the more popular derivatives is known as an "interest rate swap" which allows a company to exchange a fixed interest rate for a floating rate payment. Company A wants to benefit from falling interest rates; Company B would like to protect itself against a possible rise in interest rates. Company A "lends" B $100 million at a fixed rate (say 8 percent), and B "lends" $100 million at a variable rate. In some cases, such arrangements can greatly reduce the financing costs to the company. Each month, they balance accounts; if the variable rate is greater than 8 percent, A pays B the difference; if it is less, B pays A. Although the loan principal is recorded on the books of each company, it is an accounting fiction.

In the derivatives market, these swaps take on a value of their own. By looking at today's interest rate, investment analysts can figure out how much income a swap will generate and for whom, and then can sell the swap for an appropriate price. Derivatives often are designed to benefit from a falling interest rate. As the rate falls, the securities derive an additional value, and it is this "margin" that is sold to other investors. To add another layer of complexity, companies may exchange the payments from debts denominated in different currencies--for example, the income from U.S. Treasury bills for dividends generated by a portfolio of Japanese stocks. Each combination allows the participants to trade a different set of potential risks and benefits.

Derivatives offer higher yields than the average market rate which makes them attractive at times when short-term interest rates are low. However, when the Federal Reserve began to raise interest rates in 1994 in an effort to cool the economy, many derivatives loss value dramatically.

A survey by the General Accounting Office in early 1994 indicated that among 3,737 state and local government agencies, 288 reported using derivatives to some extent. In October, 1994, the House Banking Committee staff compiled a list of 19 government or public funds that had suffered substantial losses due to derivatives. Investors who had borrowed money to buy derivatives faced particularly harsh losses. An investment fund run by the treasurer's office of Orange County, California reported a $1.5 billion loss, partly because of derivatives. About $8 billion of the $20 billion portfolio of Orange County was invested in derivatives. About 185 cities, schools districts, and other government agencies in Southern California had money invested in that fund. The Florida Treasurer's Office reported a $175 million loss in its portfolio, partly die to derivatives.

The problem stems from the fact that some investment firms sold extremely complex securities and may not have adequately informed the customers of the risks. Local governments and other public organizations not well-versed in the vagaries of the investment marketplace only saw the opportunity for high yields on short-term investments at a time when other options were hovering around 3 percent.

The National Association of Securities dealers has recently issued a set of rules to govern the sales of government securities, which includes "structured notes," a type of derivative backed by government bonds. The Federal Reserve Board has ordered investment banks dealing in derivatives to provide customers with a more complete explanation of the pitfalls of certain risky derivatives. Derivative securities were the hottest area of investment in the early 1990's, growing to over $12 trillion in contracts by the end of 1992. But like many rapidly rising investment schemes, the fall can be even more rapid, and for unsuspecting municipal governments and other public organizations, the consequences can be devastating. The Eastern Shoshone Tribe in rural Wyoming invested nearly $5 million in mortgage derivatives in 1993 at the encouragement of a brokerage firm in Houston, Texas. The values dropped substantially leaving the 3,000 members of the tribe (70% of whom are unemployed) with little to show for their investment.

Municipal derivatives were originally developed for and sold to the municipal bond mutual fund industry. Few, if any, municipal derivatives have been sold to individual investors, but that could change at any time, since sales to individuals have been proposed at major municipal bond firms. Municipal derivatives are created by dividing a fixed-rate bond into two parts, called a floater and an inverse floater. While the interest and principal payments of the issuer remain unchanged, the division of interest payments between the floater and the inverse floater may vary during the life of the bond. The rate paid on the floater is a variable rate, determined by one of the methods used to set rates on variable rate bonds. A common method is to have a periodic auction of the floaters (often every 35 days to compete in the short-term investment market). The rate paid on the inverse floater is the difference between the fixed rate paid on the original bond and the amount paid on the floater.

To illustrate this process, assume an underwriter takes $200,000 (face value) in bonds with a 6% coupon rate, maturing in 20 years and splits this amount into two parts: $100,000 face amount of floaters and $100,000 face amount of inverse floaters. Further assume that the initial rate set on the floaters (by auction) was 3.5 percent; the $100,000 face amount of floaters receives $3,500, while the $100,000 face amount for inverse floaters receive $8,500 (i.e., the difference between the $12,000 in interest earned at the fixed rate of 6% and the amount allocated to the floaters). If short-term interest rates, the interest paid on the floaters will increase, and the interest paid on the inverse floaters will decrease. Not only will the income from the inverse floaters decline, but the price will also decline, along with bond prices generally.

Arbitrage

Arbitrage in the municipal bond market is the difference in the interest paid on an issuer's tax- exempt bonds and the interest earned by investing the bond proceeds in taxable securities. Proceeds from a bond issue are usually put into short-term investments until either they are spent on their intended use or, in the case of a refunding issue, used to call the original bonds. Both of these situations can generate arbitrage earnings. If interest rates on the investments are below the interest rates on the bonds, then there is "negative arbitrage."

During the 1980s, the federal government became concerned that municipal governments were abusing their power to issue bonds by issuing bonds unnecessarily in order to try to earn arbitrage. The 1986 Tax Reform Act established a variety of restrictions and regulations designed to prevent abuse. Federal arbitrage rules state that an issuer cannot invest tax-exempt bond proceeds at a higher yield than the interest rate on the bond issue, except in specific circumstances. More accurately, the yield on the investments can only be 1/8 of 1% higher, or arbitrage restrictions apply. For example, if the yield on the refunding bond is 6%, the issuer is limited to a 6.125% return on the investment of the bond proceeds. The issuer can purchase special low-yield U.S. Treasury securities, called the state and local government series, to meet this requirement if the normal market instruments are paying more. However, there are exceptions to the yield restriction.

Arbitrage may be earned for certain temporary periods if the bond proceeds are used for certain kinds of projects and spent within specified periods of time. At the end of the permitted temporary period, the issuer must restrict the yield on the remaining proceeds.

Sometimes the issuer does earn prohibited arbitrage that had not been foreseen. If this happens, any earnings in excess of the bond yield must be returned to the U.S. Treasury in a process called "rebating." There are two possible penalties for an issuer failing to comply with rebate requirements: (1) the IRS can declare the bonds taxable retroactive to the date of issue, or (2) the IRS can assess a monetary penalty. Failure to adhere to federal arbitrage provisions can, in certain circumstances, cause the municipal bonds to lose their tax-exempt status.

Another regulation limits advance refundings to once for each original bond issue. This limit prevents governments from repeatedly refunding the same issue each time interest rates drop in an attempt to realize even greater arbitrage earnings. Therefore, issuers must carefully choose the timing of an advanced refunding. Private activity bonds cannot be advance refunded at all. This restriction prevents the federal subsidization of private activities through tax-exempt arbitrage earnings.