Click below to read

The Palestinian Charter

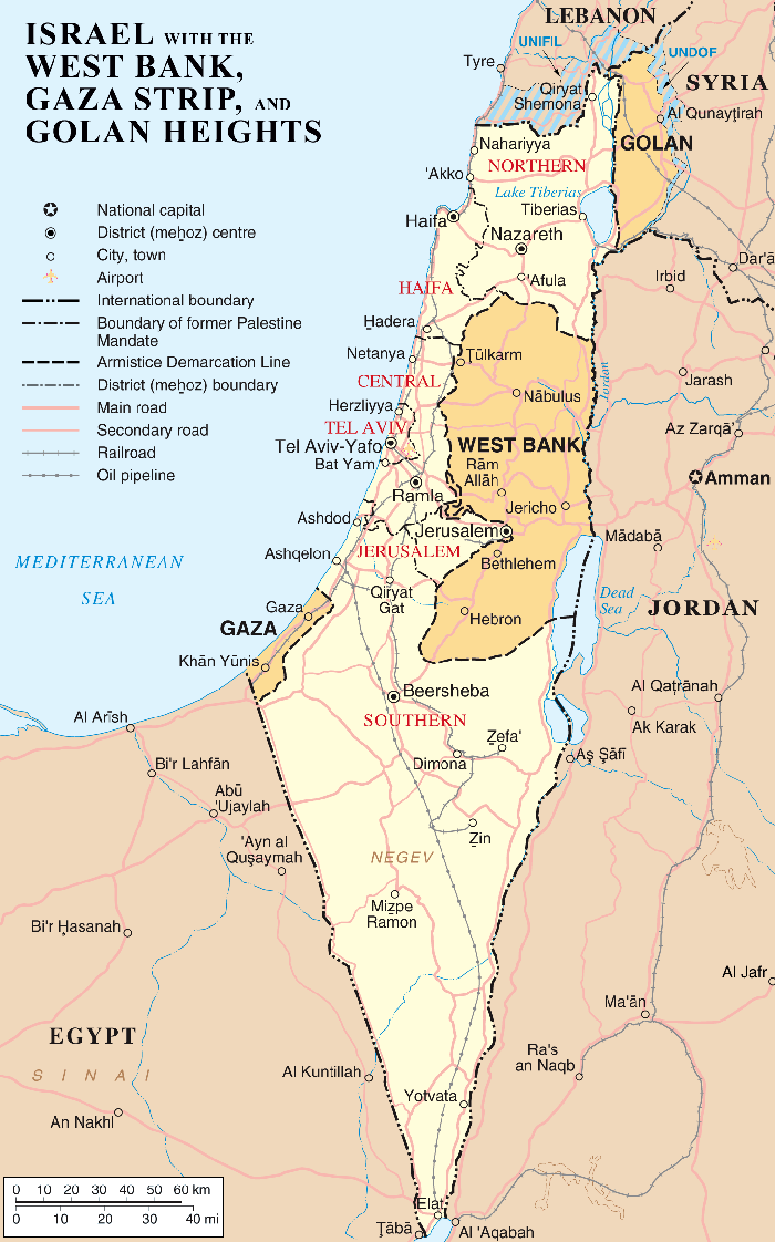

| Palestine ***In the map below, the West Bank is the land known as Palestine |

| HISTORY

Territory of the Ottoman

Empire in 1890 After

the Ottoman

conquest, the name "Palestine" disappeared as the official name of an

administrative unit, as the Turks often called their (sub)provinces

after the

capital. Since its 1516 incorporation in the Ottoman Empire, it was

part of the vilayet

(province)

of

Damascus-Syria until 1660, next of the vilayet of Saida

(Sidon), briefly interrupted by the 7 March 1799 - July 1799 French

occupation

of Jaffa, Haifa, and Caesarea. During the siege of Acre

in 1799, Napoleon

prepared a proclamation declaring a Jewish state in Palestine. On 10

May 1832

it was one of the Turkish provinces annexed by Muhammad Ali's

shortly imperialistic Egypt

(nominally still Ottoman), but in November 1840 direct Ottoman rule was

restored. Still

the old name remained in popular

and semi-official use. Many examples of its usage in the 16th and 17th

centuries have survived.[95]

During the 19th century, the "Ottoman Government employed the term Arz-i

Filistin (the 'Land of Palestine') in official correspondence,

meaning for

all intents and purposes the area to the west of the River Jordan which

became

'Palestine' under the British in 1922".[96]

Amongst the educated Arab public, Filastin was a common

concept,

referring either to the whole of Palestine or to the Jerusalem sanjaq

alone[97]

or just to the area around Ramle.[98] Ottoman

rule over the region lasted

until the Great War

(World War I)

when the Ottomans sided

with Germany

and the Central Powers.

During World War I,

the Ottomans were driven from much of the area by the United

Kingdom during the dissolution of the

Ottoman Empire. In

European usage up to World War I,

"Palestine" was used informally for a region that extended in the

north-south direction typically from Raphia

(south-east of Gaza)

to the Litani River

(now in Lebanon). The western

boundary was the sea, and the eastern boundary was the poorly-defined

place

where the Syrian desert began. In various European sources, the eastern

boundary was placed anywhere from the Jordan River to slightly east of Amman.

The Negev Desert

was not included.[99] Under

the Sykes-Picot Agreement

of 1916, it was

envisioned that most of Palestine, when freed from Ottoman control,

would

become an international zone not under direct French or British

colonial

control. Shortly thereafter, British foreign minister Arthur

Balfour issued the Balfour Declaration

of 1917, which laid

plans for a Jewish homeland to be established in Palestine eventually. The

British-led Egyptian

Expeditionary Force, commanded by Edmund Allenby,

captured

Jerusalem on 9 December,

1917 and occupied the whole of the

Levant following the defeat of Turkish forces in Palestine at the Battle of Megiddo

in September 1918 and

the capitulation of Turkey on 31 October.[100] The British Mandate

enacted English, Hebrew

and Arabic

as its three official languages. The land designated by the mandate was

called

Palestine in English, Falastin (فلسطين) in Arabic,

and in Hebrew Palestina or Eretz Yisrael

((פלשתינה

(א"י). In

April 1920 the Allied Supreme

Council (the USA, Great Britain, France, Italy and Japan) met at Sanremo

and formal decisions were taken on the

allocation of mandate territories. The United Kingdom accepted a

mandate for

Palestine, but the boundaries of the mandate and the conditions under

which it

was to be held were not decided. The Zionist Organization's

representative at

Sanremo, Chaim Weizmann,

subsequently reported to his

colleagues in London: "There

are still important details outstanding, such as

the actual terms of the mandate and the question of the boundaries in

Palestine. There is the delimitation of the boundary between French

Syria and

Palestine, which will constitute the northern frontier and the eastern

line of

demarcation, adjoining Arab Syria. The latter is not likely to be fixed

until

the Emir Feisal attends the Peace Conference, probably in Paris."[101]

In

July 1920, the French drove Faisal bin Husayn

from Damascus

ending his already negligible control over the region of Transjordan,

where

local chiefs traditionally resisted any central authority. The sheikhs,

who had

earlier pledged their loyalty to the Sharif of Mecca,

asked the British to undertake

the region's administration. Herbert

Samuel asked for the extension of the Palestine government's

authority to Transjordan, but at meetings in Cairo and Jerusalem

between Winston Churchill

and Emir Abdullah

in March 1921 it was agreed

that Abdullah would administer the territory (initially for six months

only) on

behalf of the Palestine administration. In the summer of 1921

Transjordan was

included within the Mandate, but excluded from the provisions for a Jewish National Home.[102]

On 24 July,

1922 the League of Nations approved the terms of the British Mandate

over

Palestine and Transjordan. On 16 September

the League formally approved a memorandum from Lord Balfour

confirming the exemption of Transjordan from the clauses of the mandate

concerning the creation of a Jewish national home and from the

mandate's

responsibility to facilitate Jewish immigration and land

settlement.[103]

With Transjordan coming under the administration of the British

Mandate, the

mandate's collective territory became constituted of 23% Palestine and

77%

Transjordan. Transjordan was a very sparsely populated region

(specially in

comparison with Palestine proper) due to its relatively limited

resources and

largely desert environment. The

award of the mandates was

delayed as a result of the United States' suspicions regarding

Britain's

colonial ambitions and similar reservations held by Italy about

France's

intentions. France in turn refused to reach a settlement over Palestine

until

its own mandate in Syria became final. According to Louis, Together

with the American protests against the issuance of

mandates these triangular quarrels between the Italians, French, and

British

explain why the A mandates did not come into force until nearly four

years

after the signing of the Peace Treaty....

The British documents

clearly reveal that Balfour's patient and skillful diplomacy

contributed

greatly to the final issuance of the A mandates for Syria and Palestine

on September 29,

1923.[104]

Even

before the Mandate came into

legal effect in 1923 (text),

British terminology

sometimes used '"Palestine" for the part west of the Jordan River and

"Trans-Jordan" (or Transjordania) for the part east of the

Jordan River.[105][106] In

the years following World War II,

Britain's control over Palestine became increasingly tenuous. This was

caused

by a combination of factors, including:

Finally

in early 1947 the British

Government announced their desire to terminate the Mandate, and passed

the

responsibility over Palestine to the United

Nations.

Refugees There

are 4,255,120 Palestinians registered as refugees with the United

Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA). This number includes the

descendants of regugees from the 1948 war, but excludes those who have

emigrated to areas outside of UNRWA's remit. Based on these

figures, almost half of all Palestinians are registered refugees.

The 993,818 Palestinian refugees in the Gaza Strip and 705,207

Palestinian refugees in the West Bank who hail from towns and villages

that are now located in Israel are included in these UNRWA

figures. UNRWA figures do not include some 274,000 people, or 1

in 4 of all Arab citizens of Israel, who are internally displaced

Palestinian refugees. |

|

|

CURRENT

STATUS Following

the 1948 Arab-Israeli War,

the 1949 Armistice

Agreements between Israel

and neighboring Arab states eliminated Palestine as a distinct

territory. With

the establishment of Israel, the remaining lands were divided amongst

Egypt,

Syria and Jordan.

For

a description of the massive

population movements, Arab and Jewish, at the time of the 1948 war and

over the

following decades, see Palestinian exodus

and Jewish exodus from

Arab lands. From

the 1960s onward, the term "Palestine" was regularly used in

political contexts. Various declarations, such as the 15 November 1988

proclamation of a State of Palestine

by the PLO

referred to a country

called Palestine, defining its borders based on the U.N. Resolution 242

and 383

and the principle of land for peace. The Green Line

was the 1967 border established by

many UN resolutions including those mentioned above. In

the course of the Six Day War

in June 1967, Israel captured the West Bank from Jordan and Gaza from

Egypt. According

to the CIA World Factbook,[108]

of the ten million people living between Jordan and the Mediterranean

Sea,

about five million (49%) identify as Palestinian,

Arab, Bedouin

and/or Druze.

One million of those are citizens of Israel.

The other four million

are residents of the West Bank and Gaza, which are under the

jurisdiction of

the Palestinian National

Authority. In

the West Bank, 360,000 Israeli

settlers live in a hundred scattered settlements with

connecting

corridors. The 2.5 million West Bank Palestinians live in four blocs

centered

in Hebron, Ramallah, Nablus, and Jericho. In 2005, all the Israeli

settlers

were evacuated from the Gaza Strip

in keeping with Ariel Sharon's plan

for unilateral disengagement, and control over the area was transferred

to the

Palestinian Authority. THE PALESTINIAN PEOPLE The

Greek

toponym Palaistinê (Παλαιστίνη), with which the Arabic Filastin

(فلسطين) is cognate, first occurs in the

work of the Ionian

historian Herodotus,

active in the middle of the 5th century BCE, where it denotes generally[6]

all of the coastal land, including Phoenicia,

down to Egypt.

In expressions where he employs it as an ethnonym, as when he speaks of

the

'Syrians of Palestine'[7]

it refers to a population distinct from the Phoenicians, and thus

probably

Philistines, though it may also cover several other tribes and ethnic

groups

present in the area, including the Jews.[8].

The word bears comparison to a congeries of ethnonyms in Semitic

languages,

Egyptian Prst, Assyrian Palastu, and the Hebraic Plishtim,

the latter term used in the Bible to signify the Philistines. The

Arabic word Filastin has

been used to refer to the region since the earliest medieval

Arab geographers

adopted the Greek

name. Filastini (فلسطيني), also

derived from the Latinized

Greek

term Palaestina (Παλαιστίνη), appears to have been used as an Arabic adjectival noun

in the region since as early as

the 7th century CE.[9] During

the British Mandate of

Palestine, the term

"Palestinian" was used to refer to all people residing there,

regardless of religion or ethnicity, and those granted citizenship by

the

Mandatory authorities were granted "Palestinian citizenship".[10] Following

the 1948 establishment

of the State of Israel

as the national homeland of the Jewish people,

the use and application of the terms "Palestine" and

"Palestinian" by and to Palestinian

Jews largely dropped from use. The English-language

newspaper The Palestine Post

for example — which,

since 1932, primarily served the Jewish community

in the British Mandate of

Palestine — changed its

name in 1950 to The Jerusalem Post.

Jews in Israel

and the West Bank

today generally identify as Israelis.

Arab citizens of

Israel identify

themselves as Israeli and/or Palestinian and/or Arab.[11] The

Palestinian National

Charter, as amended

by the PLO's Palestine National

Council in July 1968,

defined "Palestinians" as: "those Arab nationals who, until

1947, normally resided in Palestine regardless of whether they were

evicted

from it or stayed there. Anyone born, after that date, of a Palestinian

father

— whether in Palestine or outside it — is also a Palestinian."[12]

This definition also extends to, "The Jews who had normally resided in

Palestine until the beginning of the Zionist

invasion." The Charter also states that "Palestine with the boundaries

it

had during the British Mandate, is an indivisible territorial unit."[13][12] Palestinian perceptions of identity In

his 1997 book, Palestinian

Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness,

historian Rashid

Khalidi notes that the archaeological strata that denote the

history

of Palestine—encompassing

the Biblical,

Roman, Byzantine,

Umayyad,

Fatimid,

Crusader,

Ayyubid,

Mamluk

and Ottoman

periods—form part of the identity of the modern-day Palestinian people,

as they

have come to understand it over the last century.[14]

Khalidi stresses that Palestinian identity has never been an exclusive

one,

with "Arabism, religion, and local loyalties" continuing to play an

important role.[15] Echoing

this view, Walid Khalidi

writes that Palestinians in Ottoman

times were "[a]cutely aware of the distinctiveness of Palestinian

history

..." and that "[a]lthough proud of their Arab heritage and ancestry,

the Palestinians considered themselves to be descended not only from

Arab

conquerors of the seventh century but also from indigenous peoples

who had lived in the country

since time immemorial, including the ancient Hebrews

and the Canaanites

before them."[16]. Ali

Qleibo, a Palestinian anthropologist,

explains how identity is "a discursive narrative that validates the

present by selecting events, characters, and moments in time as

formative

beginnings."[17]

Qleibo critiques Muslim historiography for assigning the beginning of

Palestinian cultural identity to the advent of Islam in

the seventh

century.[17]

In describing the effect of such a historiography, he writes: "Pagan

origins are

disavowed. As such the peoples that populated Palestine throughout

history have

discursively rescinded their own history and religion as they adopted

the

religion, language, and culture of Islam."[17] According

to Salim Tamari, the

'nativist' ethnographies

produced by Tawfiq Canaan

and other Palestinian writers and published in The Journal of the

Palestine

Oriental Society (1920-1948), were driven by the concern that the

"native culture of Palestine", and in particular peasant society, was

being undermined by the forces of modernity.[18]

Tamari continues: "Implicit in their scholarship (and made explicit by

Canaan himself) was another theme, namely that the peasants of

Palestine

represent—through their folk norms ... the living heritage of all the

accumulated ancient cultures that had appeared in Palestine

(principally the

Canaanite, Philistine, Hebraic,

Nabatean,

Syrio-Aramaic and Arab)."[18] The

folklorist revival among

Palestinian intellectuals such as Nimr Sirhan, Musa Allush, Salim

Mubayyid, and

the Palestinian Folklore

Society of the 1970s, highlighted pre-Islamic

(and pre-Hebraic) cultural roots, re-constructing Palestinian identity

with a

focus on Canaanite and Jebusite

cultures.[18]

These efforts seems to have borne fruit as evidenced in the

organization of

celebrations like the Qabatiya

Canaanite festival and the annual Music Festival of Yabus by

the Palestinian

Ministry of Culture.[18]

Nonetheless, some Palestinians, like Zakariyya Muhammad, have

criticized the

"Canaanite ideology" as an "intellectual fad, divorced from the

concerns of ordinary people."[18] Emergent nationalism(s) The

timing and causes behind the

emergence of a distinctively Palestinian national consciousness among

the Arabs of

Palestine are

matters of scholarly disagreement. Rashid

Khalidi argues that the modern national identity of

Palestinians has

its roots in nationalist

discourses that emerged among the

peoples of the Ottoman empire

in the late 19th century, and

which sharpened following the demarcation of modern nation-state

boundaries in

the Middle East

after World War I.[15]

Khalidi also states that although the challenge posed by Zionism

played a role in shaping this identity, that "it is a serious mistake

to

suggest that Palestinian identity emerged mainly as a response to

Zionism."[15] In

contrast, historian James L.

Gelvin argues that Palestinian

nationalism was a direct

reaction to Zionism. In his book The Israel-Palestine Conflict: One

Hundred

Years of War he states that “Palestinian nationalism emerged during

the

interwar period in response to Zionist

immigration and settlement.”[19]

Gelvin argues that this fact does not make the Palestinian identity any

less

legitimate: Whatever

the causal mechanism, by

the early 20th century strong opposition to Zionism and evidence of a

burgeoning nationalistic Palestinian identity is found in the content

of

Arabic-language newspapers in Palestine, such as Al-Karmil

(est. 1908)

and Filasteen (est. 1911).[20]

Filasteen, published in Jaffa by

Issa and Yusef al-Issa,

addressed its readers as "Palestinians",[21]

first focusing its critique of Zionism around the failure of the

Ottoman

administration to control Jewish immigration and the large influx of

foreigners, later exploring the impact of Zionist land-purchases on

Palestinian

peasants ((Arabic: فلحين,

fellahin),

expressing growing concern over land dispossession and its implications

for the

society at large.[20] The

historical record also reveals

an interplay between "Arab" and "Palestinian" identities

and nationalisms. The idea of a unique Palestinian state separated out

from its

Arab neighbors was at first rejected by some Palestinian

representatives. The

First Congress of Muslim-Christian Associations (in Jerusalem,

February 1919), which met for the purpose of selecting a Palestinian

Arab

representative for the Paris Peace

Conference, adopted the

following resolution: "We consider Palestine as part of Arab Syria, as

it

has never been separated from it at any time. We are connected with it

by

national, religious, linguistic,

natural, economic and geographical bonds."[22]

After the fall of the Ottoman

Empire and the French conquest of Syria,

however, the notion

took on greater appeal. In 1920, for instance, the formerly

pan-Syrianist mayor of Jerusalem,

Musa Qasim Pasha

al-Husayni, said

"Now, after the recent events in Damascus,

we have to effect a complete change in our plans here. Southern Syria

no longer

exists. We must defend Palestine".[citation needed] In

1922, the British authorities

over Mandate Palestine

proposed a draft constitution

which would have granted the Palestinian Arabs representation in a

Legislative

Council. The Palestine Arab delegation rejected the proposal as "wholly

unsatisfactory," noting that "the People of Palestine" could not

accept the inclusion of the Balfour Declaration

in the constitution's

preamble, as the basis for discussions, and further taking issue with

the

designation of Palestine as a British "colony of the lowest order."[23]

The Arabs tried to get the British to offer an Arab

legal establishment again roughly ten years later, but to no avail.[24] Conflict

between Palestinian

nationalists and various types of pan-Arabists

continued during the British Mandate, but the latter became

increasingly

marginalized. Two prominent leaders of the Palestinian nationalists

were Mohammad Amin

al-Husayni, Grand Mufti of

Jerusalem,appointed by the British, and Izz ad-Din al-Qassam.[25]

Followers of Sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam, who was

killed by the British in 1935, initiated the 1936–1939 Arab

revolt in Palestine

which began with a general strike and attacks on Jewish and British

installations in Nablus.[25]

The call for a general strike, non-payment of

taxes, and the closure of municipal governments was met and by the end

of 1936,

the movement had become a national revolt, often credited as marking

the birth

of the "Arab Palestinian identity".[25] The

"lost years" (1948 - 1967) After

the 1948 Arab-Israeli war

and the accompanying Palestinian exodus,

known to Palestinians

as Al Nakba

(the "catastrophe"), there was a hiatus in Palestinian political

activity which Khalidi partially attributes to "the fact that

Palestinian

society had been devastated between November 1947 and mid-May 1948 as a

result

of a series of overwhelming military defeats of the disorganized

Palestinians

by the armed forces of the Zionist movement."[26]

Those parts of British Mandate Palestine which did not become part of

the newly

declared Israeli state were occupied by Egypt and

Jordan.

During

what Khalidi terms the "lost years" that followed, Palestinians

lacked a center of gravity, divided as they were between these

countries and

others such as Syria,

Lebanon,

and elsewhere.[27] In

the 1950s, a new generation of

Palestinian nationalist groups and movements began to organize

clandestinely,

stepping out onto the public stage in the 1960s.[28]

The traditional Palestinian elite who had dominated negotiations with

the

British and the Zionists in the Mandate, and who were largely held

responsible

for the loss of Palestine, were replaced by these new movements whose

recruits

generally came from poor to middle class backgrounds and were often

students or

recent graduates of universities in Cairo, Beirut

and Damascus.[28]

The potency of the pan-Arabist

ideology put forward by Gamel Abdel Nasser—popular

among Palestinian

for whom Arabism was already an important component of their identity[29]—tended

to obscure Recent

developments in Palestinian identity (1967 - present) Since

1967, pan-Arabism has

diminished as an aspect of Palestinian identity. The Israeli capture of

the Gaza Strip

and West Bank

in the 1967 Six-Day War

prompted fractured Palestinian

political and militant groups to give up any remaining hope they had

placed in

pan-Arabism. Instead, they rallied around the Palestine Liberation

Organization

(PLO) and its nationalistic orientation.[31]

Mainstream secular

Palestinian nationalism was grouped together under the umbrella of the

PLO

whose constituent organizations include Fateh and

the Popular Front for

the Liberation of

Palestine, among others. [32]

These groups have also given voice to a tradition that emerged in 1960s

that

argues Palestinian nationalism has deep historical roots, with extreme

advocates reading a Palestinian nationalist consciousness and identity

back

into the history of Palestine over the past few centuries, and even

millennia,

when such a consciousness is in fact relatively modern.[33] The

Battle

of

Karameh and the events of Black September in

Jordan contributed to

growing Palestinian support for these groups. In 1974, the PLO was

recognized

as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people by the

Arab

states and was granted observer status as a national liberation

movement by the United

Nations that same year.[5][34]

Israel rejected the resolution, calling it "shameful".[35]

In a speech to the Knesset,

Deputy Premier and Foreign Minister Allon outlined

the government's view that: 'No one can expect us to recognize the

terrorist

organization called the PLO as representing the Palestinians—because it

does

not. No one can expect us to negotiate with the heads of terror-gangs,

who

through their ideology and actions, endeavour to liquidate the State of

Israel.'[35] The

identity of Palestinians has

been a point of contestation with Israel. Golda Meir expounded the

early

position in her famous remark that: 'It

was not as though there was a

Palestinian people in Palestine considering itself as a Palestinian

people and

we came and threw them out and took their country away from them. They

did

not exist.'[36] .

The British historian Eric Hobsbawn

allows that an element of justness can be discerned in sceptical

outsider views

that dismiss the propriety of using the term 'nation' to peoples like

the

Palestinians: such language arises often as the rhetoric of an evolved

minority

out of touch with the larger community that lacks this modern sense of

national

belonging. But at the same time, he argues, this outsider perspective

has

tended to 'overlook

the rise of mass national

identification when it did occur, as Zionist and Israeli Jews notably

did in

the case of the Palestinian Arabs.'[37] .

From 1948 through until the

1980’s, according to Eli Podeh, professor at Hebrew

University, the textbooks used in Israeli schools tried to

disavow a

unique Palestinian identity, referring to 'the Arabs of the land of

Israel'

instead of 'Palestinians.' Israeli

textbooks now widely use the term 'Palestinians.' Podeh

believes

that Palestinian textbooks

of today resemble

those from the early years of the Israeli state.[38] Various

declarations, such as the

PLO's 1988 proclamation of a State of Palestine,

have further served to

reinforce the Palestinian national identity.[citation needed]

Today,

most Palestinian organizations conceive of their struggle as either

Palestinian-nationalist or Islamic in nature, and these themes

predominate even

more today. Within Israel itself, there are political movements, such

as Abnaa

el-Balad that assert their Palestinian identity, to the

exclusion of

their Israeli one. |