Review written by Floyd Skloot

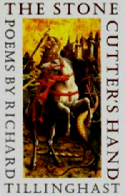

The Stonecutter's Hand

by Richard Tillinghast. David R. Godine, 1995. $19.95

ISBN 156792011X

The first nine poems in Richard Tillinghast's new collection take us on a whirlwind tour. From Anatolia, that part of Turkey which is in Asia, we go to the heart of urban Manhattan, zip back in time to southern Italy, on to Savannah, take a train ride along the Hudson River to Rhinebeck, find ourselves in a room in some unnamed town with "luggage placed by the door," move to Belgrade, and finally come to western Ireland, where we are to stay a while, with a few side-trips to Dublin or to distant mythic worlds.

What prompts such wanderings? Robert Louis Stevenson once said, "I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel's sake. The great affair is to go." This impulse toward movement, whether for adventure or wanderlust or out of deep necessity, is a staple of contemporary American life and literature. For Tillinghast in the poems of The Stonecutter's Hand, the urgency—the impulse to go—rises from a need to strip the self down to its essence, to relocate intimacy and a sense of community by immersing himself in remoteness. The poems reveal an ongoing tension between inner and outer worlds, between natives and visitors, "looking out or looking in," and this seems to be a condition Tillinghast finds vital to the poetic process. He places himself exactly between those poles, not quite at home but not simply a tourist. The book's marvelous first poem, "Anatolian Adventure" begins by stating a theme whose variations are heard throughout the collection: "Impedimenta of the self /Left behind somewhere, or traded / For a bag with good straps." With the impedimenta of self abandoned, moments of discovery turn up along the way, as in "An Elegist's Tour of Dublin," where the Georgian brick buildings "all slated for demolition" remind him that "we're all, / I'm sorry to say, Transitional," or in "The Winter Funerals," where we see him come back from a funeral in the village where he has been staying, "pull on my boots / And squelch out among the cabbages and beets," only to be transformed by hearing "that spring voice, invisible / Or nearly so, that weightless, redbreasted, sparse-feathered / Heartbeat that lifts in the battered garden, / That sings its song for no sound reason / And dies among the thorns unheralded." So far from home and saddened by the death of someone he has only just begun to know, surrounded by birdsong and by his wife's repeated playing of a piano tune, he discovers fresh signs of the value of persistence: "down in the mud the cabbages grow / With a green persistence. All day you play / That tune, that same old tune, till it's right as rain."

This fourth full-length collection of poems is Tillinghast's finest, most personal and most relaxed. Like so many of us, he is most at home when least at home, and he moves with his restless quest for peace.

This review appeared in issue No. 8 of the Harvard Review, May 1995. Copyright by Harvard Review, edited by Stratis Haviaras, Poetry Room, Harvard College Library, Cambridge MA.