Review written by Mark Jackson

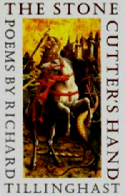

The Stonecutter's Hand

by Richard Tillinghast. David R. Godine, 1995.

Ten years after the publication of his highly acclaimed Our Flag Was Still There, Richard Tillinghast's latest collection meets, and at times exceeds, his previous achievements. His poems continue to explore historical events including the effects of W.W.II and slavery on his native South, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the demise of the Irish Artistocracy. But these poems view history from a more intimate and self-reflexive perspective than his earlier books, a perspective accentuated by love poems and elegies. His speakers travel to Ireland, Istanbul, Italy, New York and the American South, seeking a definition of "home." "'Why am I not home, where I should be?'" asks the speaker of the opening poem. Near the end of the book a speaker returns home "to take up again where we left off."

History, for Tillinghast, has never been a record of events detached from a speaker's current environment and mood—the past is ever-present in architecture, landscape and the "inner / Cosmos" of human memory. Hearing "unfamiliar birdsong" and the "controlled thunder of the IRT," the speaker of "Manhattan, Deconstruction" asks "wasn't 81st a trail once, dusty from Easter / To autumn?" A time-lapse depiction of 150 years of deforestation and high-rise construction answers the question. Tillinghast raises the poem above the objectivism of natural history by balancing his deconstruction with the speaker's concern for how New York will change during his travels. "Sighted in Belgrade" begins with a

blurred candle-shimmer

I half glimpse as I craned up from a black taxi

Rattling over cobbles, the night the king and queen

Were shot a hundred years back.

Transported across those hundred years, the speaker offers a series of vivid scenarios for the Austrian king's assassination. The incident transfixes the speaker but the present overwhelms the past and the traffic forces him to move on before he assembles a complete reconstruction of the event.

In the best of these historical poems, the convergence of past and present is subtle and mysterious. Tillinghast's economical style creates diaphanous surface into which "presences," "angels" and "visitations" surface and recede as messengers from the past. In "The Ornament," one of ten poems set in Ireland, the speaker enters the cottage of a crazed neighbor who has died recently. Sensing "her blue gaze curious over the hedge," he imagines hanging her coveted brooch on a discarded Christmas tree, "a gesture of little / Consequence. Not a living soul / Noticed. A crow cawed, and flapped from the chimney." These visitations also occur in the present. In "Convergence" a montage of dream-like sensations and images are finally corporealized as the intermittent pain of an abscessed tooth:

What trick of the night's is it, that you wake

Chilled and alert, fingering

A soreness, picturing cells

Gone rife and hungering-

That you know, as the doctor nods you politely

In, what news he has to give you?

The poems that do explore the past find it a place in which artistic perfection and grace reside. The fire that destroys an abbey also consumes "an achieved oneness / Of mason and plasterer" and sensations experienced in childhood accrue a celestial aura:

Cozy holdings, the heart's iambic thud

And sly wanderings—lip-touchings, long summers

The rain's pourings and pipings heard from bed;

Earth-smell of old houses, airy ceilings,

A boy's brainy and indolent imaginings.

This reverence for the past can degenerate into nostalgia and generalized language: "From the raptures all I have is a snapshot" or "I breathe her in like the smoke / of my days." But most often, the particularity of Tillinghast's vision and his commitment to address unredeemed landscapes and non-heroic characters instills his poems with authenticity and compassion. Halfway through the collection, the movement from an artifact or sensation to a re-enactment of past events does become formulaic; most glaringly in the Ireland poems, many of which share a common landscape of "turf smoke," thatch roofs and pints of Guinness. But Tillinghast's ability to revitalize personages from the past resists this homogeneity:

I hated to think of her throwing that old shawl

Over her shoulders and pulling her gumboots on

To venture beneath the lackluster moon,

Stooping out under her low lintel

To search with a weak torch up the Galway road,

Knocking on every cottage door

To ask had they seen her sister,

Who everybody knew was ten years dead.

("The Ornament")

Tillinghast studied with Robert Lowell at Harvard and many of these poems convey a confidence in images reminiscent of Lowell's "The Drinker," "For the Union Dead," and "Father's Bedroom." "Southbound Pullman, 1945" communicates the vast and subjective phenomenon of a hometown's ignorance of the trauma of war with a soldier's "nightmare scream" followed by "bands and a convertible." "Aubade" lists images without editorial: "A stocking, a twisted undergarment, shoes. / Empty matchbooks, full ashtrays, / fume of brandy over a glass." But the objects that comprise the list do not remain disparate entities. The absence of commentary grants each image an innate importance and spurs a reader to link them into a compelling narrative. The matchbooks and ashtrays attest to a night of tension. The man has wakened and views the woman getting "that last twenty / minutes of sleep she likes," "luggage placed by a door" suggests he will leave, his keys surrendered "on a Queen Anne table."

"Table," from the Turkish of Edip Cansever, is the finest of these imagistic poems. A man heaps a table with the things of his life:

He put eggs and milk on the table.

He put there the light that came in through the window,

Sound of a bicycle, sound of a spinning wheel.

The softness of bread and weather he put there.

On the table the man put

Things that happened in his mind.

The poem expresses "the gladness of living" through an abundance of images. We encourage the man to continue "piling things on" and compile our own list of materials to be added. Certainly a great deal must have been discarded to arrive at these provocative lines. A reader's contributions of the motivations for the objects chosen by the speaker allows the poem to unfold like an actual occurrence, rather than feeling "written" and complete before a reader arrives.

Tillinghast occasionally feels the need to buttress his images with decorative endings, "Outside, the million tongues of the city sleep, / and the blue Atlantic draws a breath." And he allows intense emotions to overburden the internal rhyme and syntax of a line: "Then a winey ambuscade of espaliered / Quinces, overripe and unpicked, whets / His sense of loss." But these occurrences are rare and even when the language falters, the authenticity of emotion saves the poem from bathos.

This collection (due from Godine in January) attests to Tillinghast's proficiency in the formal aspects of the art. Most of these poems are internally or end-rhymed and use prosody, not as a formula, but as a tool to accentuate a poem's emotional force through metrical substitutions and line breaks. But for all this rigor, they are poems formed with a sculptor's delicacy. They achieve their full effect when read aloud and the spaciousness created by unmodified images encourages multiple readings. Tillinghast's talent for combining prosaic and imagistic styles produces fresh, lucid verse and reaffirms his status as a major talent.

The summer had been lunches and glances,

Involved afternoons, keys and sudden kisses.

Our train, the Adirondack, sniffing coolness up the track,

Sensing greenness and a breezy exhalation

Of mountain coves, left New York in the station,

Burrowed, and surfaced to blind windows and burnt brink,

A scuffed football launched into emptiness. Then the Hudson:

Brimming, expansive, forbidding, scaled to its city.

A yacht cut the putty waves. The train blew a diesel spondee.

From "The Adirondack" in The Stonecutter's Hand.

Mark Jackson is consultant in poetry to the Atlantic Monthly and teaches creative writing at Boston University.

This review is from and copyrighted by the Boston Book Review, Vol. 2, Issue 1, December 1994.