Joss Kiely

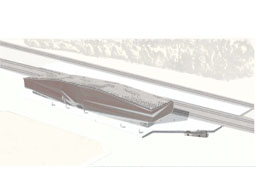

A train car itself is not a place; it is never here nor there, but forever relegated to the in between. It is a completely fictional entity, a capsule for the mobilization of people and goods across a landscape and through space.

At its core, transportation architecture can be read as an architecture of the interstitial; it exists as the spaces between “things” rather than as “things” in space. It has many users, but no permanent inhabitant. It is about servicing the needs of many while profoundly impacting very few.

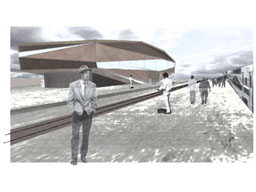

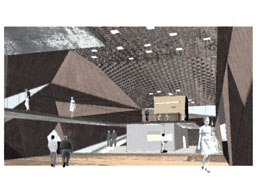

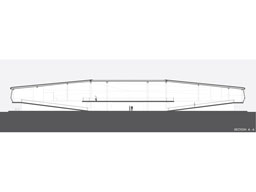

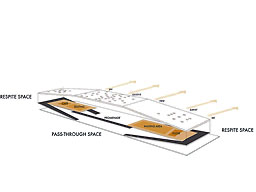

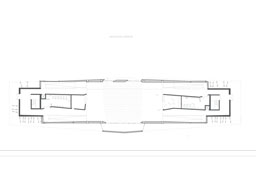

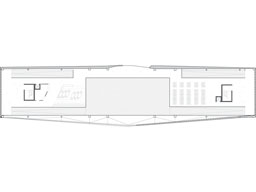

This design proposes a focus on the user as protagonist to the architecture. When the user first descends onto the platform, for one of very few moments in his journey, the user becomes master of his own schedule, mobilizing his body through space and within a timeframe that reflects his personal needs or desires. The main floor of the station is reduced to the most basic services that one might need to make one’s train on time. As the user filters up to the second floor, however, the experience becomes less about need and more about desire: it is the space where one might have a light meal or relax while awaiting a delayed train. Indeed, the main floor is about “pass-through space,” with which one must interact, whereas the upper floor is about “respite space,” with which one may interact.

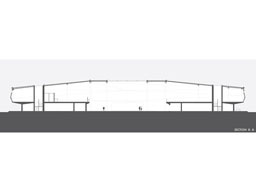

Taking its visual cues from the gritty industrial auto industry of the early to mid twentieth century, the design of the envelope employs core ten steel as a means to subvert the nostalgia that its neighboring institution so heavily embraces while at the same time testing the limits of the historicist bent of The Henry Ford and The Greenfield Village. Perhaps the architecture itself can be read as embodying a sort of “inverted nostalgia”; it is as nostalgic for the innovation Henry Ford espoused, as The Henry Ford is nostalgic for the historic era of the Model T it ardently embraces.

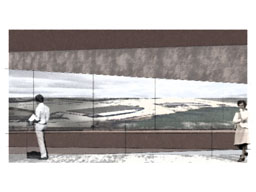

To this end, then, the visual connections from the waiting area on the upper level become paramount. The “portal,” a sliver of a window on the north side proposes a delicately commanding view of the parking lot and Michigan Avenue, a reference perhaps to the auto industry whose presence gives Dearborn reason to exist. On the south side, however, the “gallery” window slowly descends from ceiling to eye level as it traverses the façade from east to west, slowly revealing the back of the house comings and goings at the Greenfield Village, undermining the historicist façade The Henry Ford has worked so hard to erect.