from Folk Roots

No. 202 (Vol. 21 No. 10) April 2000, pp. 38-43.

Get

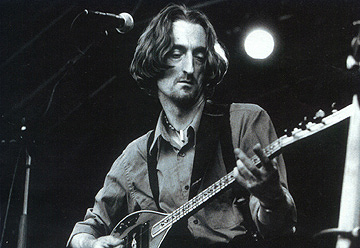

Saz Appeal

From

punk rock to bloke rock via a swarthe of the great bands of our time. Ian

Anderson unravels the unlikely tale of Lu Edmonds: have cümbüs,

will travel...

So

what do punk pranksters The Damned, world music godfathers 3 Mustaphas 3, Leeds

art-folkrockers the Mekons, bhangra pioneers Alaap, Ewan's independent daughter

Kirsty Maccoll, Tuvan stars Yat-Kha, John Lydon's '80s outfit PiL, The Waterboys,

Shriekback and Billy Bragg's Blokes have in common? Well, they are among

the bands who crop up on the scrawled CV of the man they call Uncle, otherwise

Lu Edmonds, that I'm staring at. From punk rock to the roots and back

in two action-packed decades, you might say -- and bound to be an interesting

tale. So I sat Lu down at last autumn's Berlin Womex and prised it out

of him.

So

what do punk pranksters The Damned, world music godfathers 3 Mustaphas 3, Leeds

art-folkrockers the Mekons, bhangra pioneers Alaap, Ewan's independent daughter

Kirsty Maccoll, Tuvan stars Yat-Kha, John Lydon's '80s outfit PiL, The Waterboys,

Shriekback and Billy Bragg's Blokes have in common? Well, they are among

the bands who crop up on the scrawled CV of the man they call Uncle, otherwise

Lu Edmonds, that I'm staring at. From punk rock to the roots and back

in two action-packed decades, you might say -- and bound to be an interesting

tale. So I sat Lu down at last autumn's Berlin Womex and prised it out

of him.

The first name

and dates on the Edmonds list are The Damned 1977/78, but he surely didn't pick

up an instrument and walk fully fledged into a performing punk rock band.

In our 1999 Critics Poll we asked people to nominate the record that changed

their life. Was there a point where he realised there was more than electric

guitars and punk rock bands? Pre-history?

"When I was small,

the Golden Gate Quartet was a real think. My granny really liked them.

And then when the Beatles came that was totally mind-blowing -- at the time

I was in South America. A thing that changed my life there was a red clear

vinyl record of Venezuelan folk music -- absolutely beautiful songs, harps and

everything, and I really liked that. I suppose looking back, there was

a lot of Cuban stuff."

"I had a couple

of friends in school, and my brother played. It was really pick up the

guitar and bash and bash and bash and bash. And then I went on the building

sites in London -- bash, bash, bash, bash, except this time concrete -- and

saved up money to buy amps. There was an idea of putting a band together

with a friend, and it went here and there and basically I went out of London

at a critical point. I'd just moved back, with a guitar, and stayed with

a girlfriend who had a place, and thought 'What am I going to do?'. And

I scanned through Melody Maker one day: 'Interesting guitarist

wanted. Into Damned, MC5 and Stooges.' I thought 'two out of three's

not bad' and I went down and it was The Damned, goddamn it!"

What was the Kirsty

MacColl connection -- live or on records?

"Both. We

did studio stuff and then went on what was for her a very difficult tour around

Ireland, the ballrooms, because she had a very bad case of stage fright -- around

1980. We had Terry Woods playing with us. It was a really bizarre

bunch, with muggins here on the guitar. We did the ballrooms, from Lochrae

to Letterkenny, all the way down to Cashel, Limerick, Dublin. Frank Murray

was tour managing it, who was the Pogues manager later, and before that he was

Thin Lizzy's tour manager, so it was really Irish. It was great.

We went to Strand Hill with Planxty's manager who ran a pub and who put the

gig on there."

We progress a

bit further down the time line. He moved to Szegerely, or Szegerely moved

to him (I never really got any sense out of anybody as to how the 3 Mustaphas

3 coalesced). Would that be the first time he played something other than

guitar in a live band? How did he find himself the owner of things like

a saz or a cümbüs?

"As any fule kno,

anyone who has a guitar and tries to tune it will find themselves chasing their

tail. For your non-musical readers, if you tune a guitar so the E sounds

really great, the moment you play a G, the B will sound sharp, and this is because

of the imponderables of the badly tempered piano by J.S. Bach, and I could never

tune my guitar. I used to agonise and wonder why and I found out that

it's impossible to tune guitars, and I started to become more and more interested

in ancient instruments. Egyptian wall paintings also had guitars on them,

except they looked different, and [unconventional composer] Harry Partch

was put in front of my face by a very good friend of mine called Bill Hodgkinson

who is now up an alp in Switzerland. He opened me to these two subversive

thoughts: that there is something beyond and behind the guitar, and ever

since then I suppose I've been doing both, in both directions, and I suppose

sideways to some extent."

"This really coalesced

in a Mustaphic way in 1986, when I was at a loose end and somebody said, 'Why

don't you go to Istanbul? Here's an address, a place where you can buy

sazes.' And now, 15 or 16 visits later I'm now the very sick owner of

maybe 10 cümbüses. I make my own necks, and carve them myself,

and I have a few people we all get together and it's like a laboratory with

all the body parts, and wood shavings all over the floor. There are three

bodies, and there are six necks, and I've added three more necks and I interchange

them as well. And so you get out of playing guitars which have these metal

frets, which are alright up to a point. The Turks have got this very sweet

way of making these wire frets -- three times round the thing and a little knot

which doesn't really bother you. So once you've got that it's moveable

frets, so not only are you tuning your guitar but you can also tune the frets,

you can slant them this way or that. Here's some free information for

guitarists out there: all major notes should be 16 percent flat, and all

minor notes should be 16 percent sharp. Minor and major should actually

be 31.5 percent nearer to each other, and if you go right inside there, that

is the blue note, that everyone knows about. So once you know that, you

start finding out that there's lots of other places on the neck where you have

more blue notes, and this is what people like, note that are in between the

notes."

"The cümbüs

is basically a spun-aluminum cooking pot with an alloy rim, and you've got a

9-inch skin on it (it's very strange how British imperial measurements have

survived the fall of Suez!). And there's a three-footed bridge that's

just floating on the skin, a lot higher than a banjo bridge. And then

you've got a twelve-string tailpiece which goes over the bridge and up the neck

and attaches. But the neck is attached only by a bolt. It's like

on a fulcrum -- there's nothing between the neck and the body. There's

no bar, nothing. You adjust the action by tightening or loosening the

bolt, which is very handy. And you just whip it apart and put all your

socks and pants in the body, and then you can travel with it! It's very

practical. It's fretless, and because of that it's hard to play, because

the moment you put your fingers slightly off it you know about it."

"There's quite

an interesting story about it as told to me by the grandson of Zeynel Abidin.

He was some kind of major industrialist at the time of Atattürk, and Atattürk

was getting drunk one night and moaning how there was no such thing as a proper

Turkish instrument, and all they had were borrowings from the West and the Arabic

or the Persian. So off went Zeynel Abidin, who probably had a cooking

pot factory or something, and he spun something together and produced this thing

and brought it round a few nights later, with a musician who obviously knew

his chops. Atattürk got sozzled to the appropriate degree and this

guy brought the musician on and said 'Here you go. This is a Turkish instrument.

I invented it three days ago.' Atattürk liked it so much he said

'I'll call this cümbüs' which in Turkish means 'knees-up', 'jolly

time'. And after that the family of Abidin took the name 'Cümbüs',

so they were named by Atattürk, which was a pretty big deal in Turkey."

"In the end people

realised that this was a very cheap instrument, and all the people would actually

prefer to play an oud, so only what they called the Romans, otherwise the Gypsy

people, the Roma in Istanbul, really took to this in a big way. Word has

it that the original ones were made of copper so there was a big problem because

the Gypsies, when they get a bit poor, they just go down to the scrapyard and

trade in their cümbüs to get a bit of money."

So why would I

have found a shop full of the things in Athens, when it's such a Turkish instrument?

"Really until

recently, the cümbüs was only favoured by the Roma in Istanbul, the

Gypsy diaspora, and also in Kosovo and Macedonia. Now in the last 15 to

20 years, there's been this turn in Greece, probably coming from Nikos Papazoglou

and that album Revenge of the Gypsies where suddenly Greeks stopped being

very, very Greek Greek, and started looking beyond their borders.

A lot of the cümbüses do go where there are Gypsy communities, and

there are sazes everywhere in Greece now. The funny thing is if you go

to the Greek museum of ethnological music just underneath the Acropolis -- I

went there the other day and I was absolutely stunned because they had these

wonderful old bouzoukis and baglamas and sazes, and the thing is there's no

difference between them."

"Right now, if

you see a bouzouki in a Greek restaurant, it's a big-bellied thing with a long

neck and eight strings -- it used to have six strings. It's tuned like

the top four strings of a guitar but a tone down. It's got metal frets;

it's got that Neapolitan-mandolin-but-bigger sort of sound. A saz, on

the other hand, is again a big-bellied thing but it's more teardrop shaped.

The neck's much thinner. It's got wire plastic frets which you can move

around. It's got pegs at the end and it's got microtonal frets -- 17 or

18 frets in the octave. The strings are very close to the board, they're

much floppier, it's a longer scale and it's much 'bzoingier'. There are

six, maybe seven strings, all double chords unless you triple up on one of them.

But in Turkey there are any amount of tunings you can use."

"These

two instruments now are very distinct and they're only joined in Lebanon by

the bozok, which was played by Matar Mohamet, who was a virtuoso. His

was made for him by Armenian luthiers in Beirut, and is incredible. I've

played it. It's one of the greatest instruments I've ever laid my mitts

on. It's the construction of a Greek bouzouki with six strings, but he's

taken the middle one out so there are only four, and the frets are of the Turkish

design but with much thicker wire so you can really bend and do vibrato on it.

So in a very odd way that is where the saz and bouzouki are joined. It's

only in Lebanon. But if you go back 100 years and see all the proto-sazes

and the proto-bozoks you cannot tell the difference between them! The

bridges, the constructions. Nowadays on a saz there will be no holes on

the front. In the old days there were holes."

"These

two instruments now are very distinct and they're only joined in Lebanon by

the bozok, which was played by Matar Mohamet, who was a virtuoso. His

was made for him by Armenian luthiers in Beirut, and is incredible. I've

played it. It's one of the greatest instruments I've ever laid my mitts

on. It's the construction of a Greek bouzouki with six strings, but he's

taken the middle one out so there are only four, and the frets are of the Turkish

design but with much thicker wire so you can really bend and do vibrato on it.

So in a very odd way that is where the saz and bouzouki are joined. It's

only in Lebanon. But if you go back 100 years and see all the proto-sazes

and the proto-bozoks you cannot tell the difference between them! The

bridges, the constructions. Nowadays on a saz there will be no holes on

the front. In the old days there were holes."

We talk about

how the bouzouki has become an Irish traditional instrument since the days of

Johnny Moynihan and Andy Irvine, and how at any time in the history of a country,

particularly islands, a single sailor could have turned up with an instrument

and had a fantastic efect on the tradition of that country, but 300 years later

you'd never know, because it was never recorded. It's only because the

bouzouki in Ireland has happened in the last 40 years that we know who did it.

And so to the

Mekons... how did that connection come about? "Well I have to cite

a Mr Jim Chapman in this, a fine upstanding citizen of the management community.

It was at the time of the miners' strike, and there were all these benefits

he wanted to put together. He always loved The Mekons and knew them.,

and he just wanted to get a rhythm section, as we called it then, bass and drums.

He got Steve Goulding of Graham Parker & The Rumour and many other bands,

and he said 'Lu, you can play bass, can't you?' and I said 'If you can find

me one...' We just went into a studio and we cut Fear & Whisky

and then did all these gigs, featuring at some point Dick Taylor of The Pretty

Things, which was great. He'd just turn up on the same basis as Lol Coxhill

played with The Damned -- just turn up, it'd be 50 quid. The basic hardcore

band were John Langford, Sally Timms, Tom Greenhalgh and John Gill was there."

John Gill, who'd

been working as a studio engineer for Bill Leader, was the one who'd turned

the Mekons on to English country dance music. I regret that I never managed

to get a copy of the Mekons' The English Dancing Master. Tom Greenhalgh

once told me the last copies were dumped on a tip somewhere. A terrible

sin.

Three weeks in

the Waterboys?

"Again, Jim Chapman

got me into that. I was playing with Mike Scott, and we were doing all

these TV things. I played on the record This Is The Sea and we

did these rehearsals at like 187 decibels, and Mike Scott -- what a singer!

He actually met me when I was in The Damned. He was 15, and he came and

interviewed the band in Edinburgh. I vaguely remembered him as being this

very intense young chap. Afterwards, I thought, well 187 decibels equals

deaf, but that was a very good thing."

And then Shriekback.

The first and only time I ever saw Shriekback was a mind-blowing set they'd

done at the previous Berlin Womex about five years earlier than this conversation.

I still have no idea if that's what Shriekback always did, or whether that's

what it had evolved into at that point.

"It was always

very intense, and it was about grooves and it was about energies, words and

lots of things."

At which point

I totally phase Lu by suggesting that he's been in an awful lot of groups that

might once have been described as 'Art School Bands', in following if not in

origin. This clearly leaves him bewildered...

"Have I?

No, Shriekback, never. PiL? The Mekons, certainly. The Mustaphas?

I never thought of this. It's a pretty disturbing thought. Nothing

wrong with art I suppose. Without art where would you be? Dancing!

I think that bands like Fluke, sort of techno bands, they cite Shriekback as

a real seminal influence in techno, house and that sort of stuff. It's

true. In '82 and '81 there was Dave Allen from The Gang of Four, and Barry

Andrews from XTC... Were Gang of Four an art school band? They were!

XTC were Swindon beer yobs, I'm sorry... Yes, OK. You've got me

worried now..."

What the hell

was PiL like to work in?

"It was revelatory.

It was John Lydon on the vocals, I was playing guitar and at times, often increasingly

to my chagrin, keyboards. Then we had Bruce Smith on the drums, who's

with The Slits, and we had Allan Dias, who was from Connecticut, playing bass,

and he was playing with Dawson [Miller, another Mustapha by another name]

on various things. And then there was John McGeoch of the Banshees and

Magazine on the guitar and bits of keyboard as well. It was the time when

Lydon had just recorded Album with Bill Laswell and a whole host of great illuminati

of super-great musicians of the planet, like Sakamoto and Ginger Baker, and

Steve Vai, and anyone who actually doesn't like Steve Vai and thinks all that

heavy metal stuff's rubbish should actually listen to this record. That

is really incredible playing, and if you pushed him I think Steve Vai

would admit that was the best record he ever made. There was a single

that came out, Rise, and then they basically just pulled a whole bunch

of people off the street, on word of mouth, for the band."

"We were headhunted.

It's funny, but after a year we just went 'Let's have a band and everyone gets

equal splits', and that went on for a bit more. But then I developed this

extraordinary tinnitus, and I thought 'I'm gonna die' and I left the band.

And then I found out that I wasn't gonna die, so I just moved my frets, and

that's when I became very, very acoustic. But during PiL it was fascinating.

We went to Brazil, we went to all these places. We did stadium tours backing

INX. It was a very interesting experience of the famous level of playing

-- premier league -- without actually it having anything to do with me."

You could have

gone to the bar in the interval without anyone recognising you...

"Well, actually

I once fell off the stage, and no-one noticed! It was quite scary because

it was an eight-foot drop, in front of 20,000 people, and it was the first number,

after my first chord, and I just went -- aaargh! And I managed not to

land on 20 people or die, and I kept playing! I was between two huge hefty

people, and they lifted me up, and threw me back on stage. I got really

frightened then, and for the next six numbers I was by my amp with my knees

shaking -- 'what the fuck happened there!?' At the end we had to go to

the front, to the apron, and the audience cheered and I suddenly realised that

they didn't think I was a prat, that they thought it was something I did every

night. Then I went offstage -- this is where I knew that this maybe wasn't

the band for me -- and I said 'Wow that was too much' and they said 'Did you?'

Then my technician came in and said 'Where were you?' and he still didn't believe

me. And I said 'I fell off stage' and he went 'Oh, you did, did you?'."

How long were

you in Alaap? "I was in Alaap for three hours. Basically, I tried

to get Alaap to come to Berlin to do a festival, and I had to go and get all

their passports. I went to Southall on a Sunday morning and not all of

them were there. And they said 'Don't worry, we'll go to the gig, and

we'll get them there.' So we got to the gig and not all of them were there.

They set up, and it was for a big Sikh wedding, and it was quite incredible.

There was a bottle of gin, a bottle of whisky, a bottle of vodka and a bottle

of brandy on every table, for like 600 people. And eventually everybody

turned up and started setting up, and I said 'Can I get the passports now?

I just want to get the details.' And they were going 'Just wait a bit'

and I thought 'what's going on here?'"

"They all set

up and I started counting them, and I said 'You're one short, aren't you?

So where's your bass player?' Inder was on the desk. So I said,

'Well, I'll mix the band' and they said 'No, Inder's got to mix the band', and

they supposed they'd just have to play without a bass. So they went backstage

and got all their uniforms on and I said 'Look, Inder, let me mix the band',

and they said 'No, we've got a better idea. You play bass.' It was

about a minute to go. So I was at the side of the stage, behind the stack,

and the guitarist faced me and did all these chords and I had to follow him.

Some of these chord sequences were very complicated, and three hours later my

brain boiled. I came offstage and said 'Some of those chord sequences

were very complicated' and they were going 'Why? They were all very simple.

Oh -- he was just trying to impress you!' But we got through that, and

I tour managed them in Germany for a very happy three days, and they were lovely,

a great bunch."

Somewhere before

Yat-Kha, which is on my list for '94, you must have started going to very cold

places.

"I met Albert

at the proto-Womex in 1992, and I tried to get Yat-Kha involved. The last

gig that I did with PiL was in Tallin, Estonia, where I met Nick Grakhov, the

president of the Sverdlovsk Rock Club, and he knew all these people. After

that Albert went to Sverdlovsk and hung out in the big Glasnost punk explosion

of the Siberian summers of '88, '89, and '90. That's where he did his

first recording. And he was telling me about these Siberian bands:

Cholbon, probably one of the greatest bands of the last 20 years. They're

from Yakutia -- incredible band! Like New Order times ten. I saw

them eventually in Hong Kong some years later. Still great."

"I met Albert

here in Berlin. After that he was helped by Global Music Centre, Helsinki.

There were two or three festivals who actually saw Yat-Kha and put a punt on

it and brought Albert over. It slowly built up and there came a point

where Shriekback were playing with Transglobal Underground, Jah Wobble and Wimme

the joiker at Womad, Helsinki, which was the first internet-cast world music

festival, we'd like to think, as organised by Chris Lewis. And we all

played together. And we all stayed in the GMC."

Could you work

out who was playing in which band? "It got more complicated after.

But at that point we recorded Yenisei Punk which I think is the first

record that ever came out in the West, of Yat-Kha, and I kind of helped them

out because I did the engineering and playing. I actually played the gigs.

The year after, Borkowsky Akbar [Womex, Piranha Records] booked a tour

of Germany with Shriekback and Yat-Kha, and the audience went berserk.

It was a great bill!"

"We played all

together. Everyone on the stage together. It was really good.

Vey interesting. They're still very wigged-out. Albert, if he had

more means, the means of production, he'd really do a lot of stuff, because

he's very prolific. And I really wish one day I'll get to the point where

I can afford to get him a little eight-track, and set him up in Tuva.

So since then I was going to Tuva and back, and to Yakutsk, and doing these

gigs, and in Hong Kong, being their agent and their manager, and playing the

bass -- cümbüs -- in this case."

Bass cümbüs?

"It actually sounds

very good. I play that with Lol Coxhill. We do these little duets."

Ah yes, jazz sax

man Lol Coxhill. It was through him I first heard the expression 'I'm

just off to play some squeaky-bonky music'. I never knew it was really

called that until then. So after all this, I suggest, going on tour with

Billy Bragg & The Blokes must be like going on a Butlin's holiday...

"Yeah. How

can I put this? It's no trouble. It's an absolute dream. Everyone

plays together. It all works together. Lap steel and cümbüs,

and Hammond organ playing Woody Guthrie songs, and it works. Ben Mandelson

put it together, but yet again, Jim Chapman returns. He rang me up as

I was making Dalai Beldiri, Yat-Kha's latest, in Finland and he said

'Help. Wilco won't do the tour.' And I said 'I can't talk now because

I'm in the middle of a record, talk to Ben Mandelson'. And two or three

days later Ben phoned and said 'I've decided to get the Shriekback rhythm section'.

Simon Edwards and Martyn Barker were from Shriekback, and before that Simon

was in Fairground Attraction. Martyn's foreer been in Shriekback, and

he plays a lot with Sarah Jane Morris, the jazz singer. So 60 percent

of Shriekback are in The Blokes."

So the Bloke have

a quarter of the Mustaphas, three-fifths of Shriekback...

"Simon was also

in Mambo Dunya with me and Isfahani Mustapha, and in a different thing with

Justin Adams... [Jah Wobble/Natacha Atlas sideman, contributor of Lo'Jo

tales to our last issue] We've been trying to work out -- there's

Justin Adams, me and Ben; maybe there's more British guitarists, but we've all

got ouds and sazes and stuff. How many others have? Maybe others

have too. Everything I've done I've always felt in total isolation, and

seeing Justin Adams playing was 'Oh, one of us', and meeting Ben was like that."

"Then we added

Ian McLagan. He'd got in touch with Billy about a song he'd written, and

they met an they got on. Billy's always loved The Faces and The Small

Faces. So for him it's a dream. He's been in recording studios for

years, getting the Hammond out and asking 'Can you play like Ian McLagan?'

Hence, The Blokes."

A suitable case

for a Pete Frame Family Forest, by the sound of it. So has Lu got other

things on the boil, or is this enough at the moment?

"I've been very

interested, since 1991, in this trail of 'what are we doing here?' We're

musicians surrounded by all these bits of technology that make this record business

work. There's this 'market' -- I didn't think about a market when I picked

my first guitar up. The more I try and manage Yat-Kha, and produce records,

the more I wonder about things like the Internet and all the technology, so

I'm doing a lot of that as well. Not just Internet, but things like wide-band;

mobile meets Internet meets this; what's this going to do, and how do creative

people make sure the creation is rewarded and not just scotched by the sharks?"

But won't it just

be like drivers and mechanics, split into people who make the music and the

people who deal with whatever the technology is?

"But if you're

a musician you don't want to get a car mechanic to design your guitar.

So that's the situation at the moment -- the car mechanics are designing the

guitars. You really want to get the guitarists to talk to the car mechanics

and say, well maybe there is a way that you can have less sump oil on the neck!"

With this thought

we stagger off on our separate ways, Lu -- it must be said -- scratching his

head and muttering "art school bands...?"

And as we went

to press, a new Shriekback CD turned up in the mails...

back

to the Folk Roots articles page

back to the Lu Edmonds page

So

what do punk pranksters The Damned, world music godfathers 3 Mustaphas 3, Leeds

art-folkrockers the Mekons, bhangra pioneers Alaap, Ewan's independent daughter

Kirsty Maccoll, Tuvan stars Yat-Kha, John Lydon's '80s outfit PiL, The Waterboys,

Shriekback and Billy Bragg's Blokes have in common? Well, they are among

the bands who crop up on the scrawled CV of the man they call Uncle, otherwise

Lu Edmonds, that I'm staring at. From punk rock to the roots and back

in two action-packed decades, you might say -- and bound to be an interesting

tale. So I sat Lu down at last autumn's Berlin Womex and prised it out

of him.

So

what do punk pranksters The Damned, world music godfathers 3 Mustaphas 3, Leeds

art-folkrockers the Mekons, bhangra pioneers Alaap, Ewan's independent daughter

Kirsty Maccoll, Tuvan stars Yat-Kha, John Lydon's '80s outfit PiL, The Waterboys,

Shriekback and Billy Bragg's Blokes have in common? Well, they are among

the bands who crop up on the scrawled CV of the man they call Uncle, otherwise

Lu Edmonds, that I'm staring at. From punk rock to the roots and back

in two action-packed decades, you might say -- and bound to be an interesting

tale. So I sat Lu down at last autumn's Berlin Womex and prised it out

of him.

"These

two instruments now are very distinct and they're only joined in Lebanon by

the bozok, which was played by Matar Mohamet, who was a virtuoso. His

was made for him by Armenian luthiers in Beirut, and is incredible. I've

played it. It's one of the greatest instruments I've ever laid my mitts

on. It's the construction of a Greek bouzouki with six strings, but he's

taken the middle one out so there are only four, and the frets are of the Turkish

design but with much thicker wire so you can really bend and do vibrato on it.

So in a very odd way that is where the saz and bouzouki are joined. It's

only in Lebanon. But if you go back 100 years and see all the proto-sazes

and the proto-bozoks you cannot tell the difference between them! The

bridges, the constructions. Nowadays on a saz there will be no holes on

the front. In the old days there were holes."

"These

two instruments now are very distinct and they're only joined in Lebanon by

the bozok, which was played by Matar Mohamet, who was a virtuoso. His

was made for him by Armenian luthiers in Beirut, and is incredible. I've

played it. It's one of the greatest instruments I've ever laid my mitts

on. It's the construction of a Greek bouzouki with six strings, but he's

taken the middle one out so there are only four, and the frets are of the Turkish

design but with much thicker wire so you can really bend and do vibrato on it.

So in a very odd way that is where the saz and bouzouki are joined. It's

only in Lebanon. But if you go back 100 years and see all the proto-sazes

and the proto-bozoks you cannot tell the difference between them! The

bridges, the constructions. Nowadays on a saz there will be no holes on

the front. In the old days there were holes."