by

Larry

"Harris" Taylor, Ph.D.

This

is an electronic reprint and expansion of a portion of a three part series on river diving

that appeared in SOURCES (Nov/Dec.1989,

p. 27-30.). It also appeared in BEST OF SOURCES (230-232).

This material is copyrighted and all rights retained by the author. This

article is made available as a service to the diving community by the author.

This article may be distributed for any non-commercial or Not-For-Profit use.

All

rights reserved.

Swift

water river diving can be extremely hazardous. Although knowledge from reading

may assist the diverís understanding of the environment in which the diver has

chosen to play, there is no substitute for proper training. River diving is a

specialty that demands techniques and equipment beyond most recreational

training.

Go To: Home About "Harris" Articles Slides War Stories Editorials Links Fini

Recreational divers play in swift water rivers for a variety of reasons. There is, of course, the thrill and challenge of maneuvering in swift water; the ever changing current makes each dive unique, even when diving the same location a multitude of times. Historically, rivers have been highways for westward expansion, exploration and commercial development. This means that sailors, explorers and settlers have used river systems as garbage dumps for centuries. Thus, river divers find old bottles, coins, artifacts, and antiques (anything that anyone at anytime could accidentally or purposefully discard). One never knows what is to be found on any given river dive. In addition, many rivers provide divers an opportunity to recover inadvertently abandoned anchors, fishing lures and sinkers and all sorts of small boating equipment lost by recreational boaters and fishermen. Rivers along political borders have often been areas of smuggling; as such, contraband and may still be found in some locations. Some heavily trafficked rivers provide a variety of wrecks upon which to play. Basically, anything people can lose or discard, can, at some time or another, be found on a river bottom. Some rivers offer interesting geological finds ranging from fossils to a variety of minerals, including gold, as well as being archeological sources of artifacts from times past. Finally, there are those divers who assist scientists and naturalists study the river ecosystem and commercial divers who install and watch over man-made structures immersed in the river water.

"Treasure" from an inland river: old bottles and fishing tackle

One river system that has generated a substantial international diving population is the St. Clair River. This 40-mile stretch of water connects lower Lake Huron with Lake St. Clair and serves as a border between Canada and Michigan. It is one of the world's busiest rivers. Each year more than 27 million tons of commercial cargo passes along this waterway. Recreational boat traffic from the U.S. (Michigan has the most registered boats in the U.S.) and Canada add to this traffic. All the water draining from the upper Great Lakes of Michigan, Superior and Huron passes through this river on its way to the sea. The current flow here is more than 90 million gallons of water per minute. At Port Huron, under the Blue Water Bridge, the river narrows to a few hundred feet; current here consistently exceeds 10 knots.

St Clair River (blue line: upper right) Freighter moves under the Blue Water Bridge

The abundance of recoverable objects, the presence of many wrecks, the large fish population, and the utter thrill of drifting in currents exceeding 2-3 knots attract divers from a variety of regions. Many divers have died in this river. (There are 1-2 scuba diving deaths on the American side of this river annually.) Divers will, unfortunately, continue to die here. Divers have a remarkable ability to overestimate personal skill while simultaneously underestimating the awesome force of swiftly moving water. With proper training, physical fitness and equipment, swift water river diving can be an exhilarating experience. Without such training, conditioning and equipment, the river can be a terrifying and fatal place to play.

Hazards

The primary hazard in river diving is the current. The moving water can, without apparent warning, change direction and intensity. Often, swift currents are associated with poor visibility. Diving under these conditions can be like driving 100 mph at night, in the rain with only parking lights. Divers without an appreciation of limited visibility or what moving water can do are highly stressed, subject to disorientation and terror. Many river diving fatalities are divers doing their first river exploration. Regardless of previous diving experience, all divers entering swift river water (current greater than 2 knots) for the first time should do so under the direct 1:1 supervision of a locally knowledgeable experienced river diving instructor. Specialty sport diving classes in such intense current should be on a 1:1 student: instructor ratio.

The

rules are different in the world where bubbles do NOT go straight

up! Most

river bottoms are not absolutely smooth, so there is a constant problem of being

snagged in a whole host of structures, both natural and man-made.

This problem is compounded if there is active fishing in the area because

the thousands of miles of monofilament lines on our river bottoms are often

invisible, until entanglement has occurred. There is a danger of lacerations or puncture wounds from the abundant

junk that litters the river bottom. In swift water there is often little time to

avoid sharp edges from logs, pilings, wrecks, broken glass, junk metal, and

fishing lures. The current constantly erodes everything and many underwater

structures ultimately become unstable. Some

river waters are polluted from sewage or industrial manufacturing wastes. The

moving water increases heat loss and hypothermia can be an additional problem.

Finally, river diving can be strenuous and so physically demanding that

exhaustion of self and air supply becomes a real problem.

Effluent from drains & current around

pilings are unpredictable Dikes

and jettys are built to channel current flow. The currents around these devices

are often strong and unpredictable. They should be avoided, particularly by

novice river divers. Some river systems have spillways and dams. The immediate

downstream region from these spillways forms a zone of continually recycling

water (a "hydraulic") that may be impossible to leave. Such zones have

been responsible for many deaths and have earned low-head dams the nickname

"the drowning machines." Diving immediately downstream from dam or

spillway structures is hazardous and should not be done by recreational divers.

Even a small dam with a drop of only a few feet has a water force sufficient to

trap swimmers and divers. Many such small dams have been responsible for

diver fatalities.

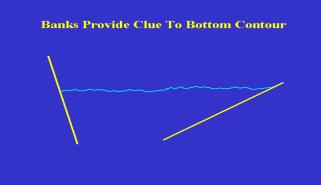

Reading

the River River divers should have some

understanding of the environment in which they play. In general, the depth of a

river is somewhat weather and seasonally dependent. Depth will increase after

heavy rains and decrease during long hot spells with no rain. Ice and man-made

structures can form dams and back-up the river, increasing depth. In some

locations, strong consistent winds can "pile-up" water on one side of

a body of water. In tidal locations, "bores" or the tidal movement of

water can reverse current flow and drastically change water depth, current

intensity and visibility. The depth is generally the deepest on the outside of

the river bend. Here the bank can provide a clue, if the bank is steep, then

most likely that steepness will continue underwater. If the bank is a gentle

slope, then the river bottom will continue in the same fashion.

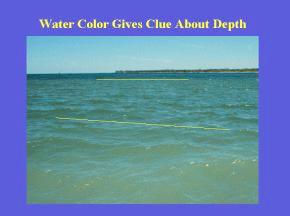

Watercolor will also provide clues to the bottom. In the illustration below left, there

are two distinctly sharp increases in water depth as indicated by a much darker

watercolor and the thin yellow lines.

Actual current flow may

vary daily and most definitely with the season. The current is the swiftest on

the outside of a bend. Local winds

can increase or decrease the current velocity depending on whether they aid or

oppose the current. In the St. Clair system, which runs north-to-south, a north

wind increases current velocity. This in turn picks up more silt and visibility

in the river goes to near zero. Strong southern winds, however, will directly

oppose the force of the current, the finer particles will drop and visibility

improves. The velocity of current, given constant volume, is a function of the

width and depth of a river.

As

the river narrows or grows shallower, the velocity will increase. This is the

situation at the mouth of the St. Clair system. Current flow, as measured by

NOAA, is roughly 90 million gallons a minute. Actual current velocity will vary

from greater than 10 knots to less than 1 knot, depending on width and depth of

the river channel at the point being measured. The increase in velocity over

shallow portions of swift moving water is particularly noticeable to divers at

depth. So, divers on a drift should anticipate an increase in current velocity

as the bottom depth decreases. Likewise,

a drop in bottom contour will generally slow current. A sharp drop may

also warn of an about-to-be-encountered upstream component of an eddy current.

Sometimes these eddy's will be accompanied by a dramatic change in current flow direction:

this can result in rapid changes of a diver's depth. Ideally,

river water will move downstream in parallel ("laminar") sheets, each

layer closer to the bottom moving slower. The friction from the bank and bottom

will decrease the velocity of the current. As one approaches irregular banks or

bottoms the flow becomes more turbulent. Indeed in some locations, in intense

current, one feels like one is in the middle of an underwater thunderstorm. The

fastest drift will be in the center of the river near the surface. The smoothest

drift looking for collectables will be in the center of the river near the

bottom. (Note, however, that the center of the river may often be too far from

shore to find too many "goodies".)

Islands

or large submerged objects will "split" the current flow and current

velocity at both ends of such objects will decrease. This leads to a "dumping" effect and debris (or

shoals) will accumulate here. Indeed, both ends of an island are excellent

places to search for artifacts and bottles. Note that this dumping effect

decreases the visibility and this is why visibility in shoal areas and the

inside of bends is usually less than other areas of the river. Whenever water

moves through restrictions or around objects an "eddy" current may

form. Eddy currents can be visualized as water moving against the primary

current to "back-fill" an abandoned space. They can form behind any

object in the river and can be used as resting locations (in the same manner as

a canoeist will use an eddy to rest and scout downstream water). In some

locations, the eddy current offers substantial upstream movement and divers can

use this current to move upstream. Large

eddy systems can be fun to dive. You enter the water and allow the eddy to take

you upstream and then return to the original entry point on the downstream

current. Note that where the eddy current meets the downstream current, there is

often a zone of turbulence and decreased visibility. These zones are also good

areas to look for "goodies" because the sudden decrease in downstream

velocity will cause objects carried by the current to drop to the bottom. The

sudden appearance of sand on an otherwise rocky bottom can be a clue that you

are about to enter a substantial eddy current.

The circular flow of an eddy

system is often apparent from above. Knowledge of existing eddy systems can be

very beneficial to divers. There is often a "standing" line where upstream and

downstream portions of current flow collide. This can provide pre-dive clues.

This collision of flow often results in the dumping of carried debris. So, in a

downstream drift, the presence of a line of silt crossing the path of the

drifting diver can provide an alert that an eddy is about to be encountered.

This can also serve as a reference to divers position along the shoreline. It

can also assist exits in known areas. For example, there is an area of the St.

Clair river system that is often a diver's exit point. This site, the Bramble

Dock, is nearly always in a strong eddy system.

While drifting downstream, the presence of a large sandy area

perpendicular to current flow provides a clue that the eddy system is about to

be entered. Since this is near a common exit point, divers will often move close to shore.

This puts them in the full force of the eddy and they must therefore expend

energy (consume more air) to move along this section of the river to their exit

point. A river knowledgeable diver will sense the eddy and move out a bit and

let the eddy can the diver to the exit point.

Although

rivers share many common hazards, each system is unique. Each different river

can provide divers with a unique and special thrill. Divers should always

consult local diving authorities to establish local conditions before diving.

River diving, like any specialty diving, can provide the diver with an

exhilarating experience. The thrill of swift current drift diving gives new

meaning to the term "diver's high." Divers who approach their diving

by obtaining proper training and equipment will find that there is great truth

to the rumor that "knowledgeable, physically fit divers have more

fun!" This is one portion

of series of articles on river diving. Others are River Diving: Equipment

River

Diving: Navigating In Currents River

Diving: Technique Lecture

Slides for the river diving course at River Go

To: Home About

"Harris" Articles

Slides

War Stories

Editorials

Links

Fini Photo

Credits: Surface

Photography: Larry "Harris" Taylor Diver

Underwater: Mike Spears St.

Clair River Map: LANDSAT Image Larry

"Harris" Taylor, Ph.D. is a biochemist and Diving Safety Coordinator

at the University of Michigan. He has authored more than 200 scuba related

articles. His personal dive library (See Alert Diver, Mar/Apr, 1997, p. 54) is

considered one of the best recreational sources of information In North America.

All

rights reserved. Use

of these articles for personal or organizational profit is specifically denied.

These

articles may be used for not-for-profit diving education