Virtual Property:

Who is the Rightful Owner of the Sword of a Thousand Truths?

WATCH: http://www.southparkstudios.com/clips/155270/the-sword-of-a-thousand-truths

[Instructions: Read every link that has READ in front of it. Links without are merely for background or your own amusement. Please read the EULA and ToS excerpts; I have provided links to the full documents, but it is not necessary that you read them in their entirety.]

I. Background (Never Underestimate How Nerdy Nerds Can Be)

Virtual property can be loosely described as computer coded “goods” existing solely in a virtual realm that function as “property” for the purposes of an emergent virtual economy. Kurt Hunt, a former Law in Cyberspace student, defines virtual property as “code that is (1) persistent - ‘they do not go away when you turn your computer off,’ and (2) interconnected – ‘[o]ther people can interact with them’”. This Land Is Not Your Land: Second Life, Copybot, and the Looming Question of Virtual Property Rights, 9 Tex. Rev. Ent. & Sports L. 141, 145 (2007-2008). The concept of virtual property most often comes up in the context of persistent multiplayer computer games such as Second Life, the World of Warcraft, and Eve Online.

The “goods” in such online worlds can take a number of forms, from developer-created “gear” earned for in-game characters, to user-created “items” for trade and sale between characters, to in-game currency, to virtual “land” in the game universe. Such items can perform a function within the game, or be purely cosmetic. These goods are the subject of often quite sophisticated and dedicated market economies. For example, take a brief look at The Undermine Journal page for one of the three in-game auction houses available on just one of World of Warcraft’s 241 North American servers: https://theunderminejournal.com/?realm=H-Uldaman (nerd alert: this happens to be my old server).

While often such economies take place solely in-game, “black markets” selling in-game items, currency, and characters for real currency have existed for years. Currency converters for exchange rates between in-game currencies and “real world” currencies abound, such as the EVE ISK (the currency for EVE Online) Currency Converter: http://isk.thealphacompany.net/?isk=480000000#.

What has changed in recent years is the willingness of game developers and publishers to establish official channels for the sale and trade of purely virtual property. The Diablo III Real Money Auction House http://www.forbes.com/sites/insertcoin/2012/06/13/why-diablo-3s-real-money-auction-house-should-not-be-your-summer-job-2/ induced an internet furor when it was introduced, but will be shutting down next year. Second Life has both in-game currency and real-life currency auctions for virtual land: http://usd.auctions.secondlife.com/.

“Virtual” property goods also typically fall into one of two categories: 1) “developer-created”, and 2) “user-created.” Developer-created goods are those designed by the developer from the game, and thus owned by the developer. Every piece of clothing and equipment worn by this Night Elf Priest from the World of Warcraft, for example, is developer-created, and can only be “earned” by playing the game itself:

“User-created” goods, in comparison, are designed and created by users of the game software, usually by way of licensed-access to parts of the game’s software. In Valve Corporation’s DOTA 2, for example, users are free to submit and then sell (through Valve’s store) gear, artwork, and units that other users can purchase and see in the game itself. The “courier” unit here is one such example: http://www.dota2.com/store/itemdetails/10192. The creators of such items get 25% of the purchase price, which can add up to a sizable income for both Valve and the creator:

READ: Phill Cameron How to make a living selling virtual hats, IGN.com (April 16, 2013, available at http://www.ign.com/articles/2013/04/16/how-to-make-a-living-selling-virtual-hats).

N.B.: The term “virtual property” has been commonly distinguished from “digital property,” which more properly describes digital data, including Internet accounts, identification data, and intellectual property rights. What differentiates “virtual” property from “digital” property is not only the way that virtual property “feels” like physical or real property, but also the amount and type of legal protection received. “Digital property” receives some protection through various means, including privacy common law, intellectual property law, and the like. “Virtual property” has comparatively received little official legal attention, whether legislative or judicial.

Is this distinction a good one? What are the policy implications of “digital property” and “virtual property” that lead to them being treated differently by the law?

II. What Should Govern Virtual Property?

The above section demonstrates that people certainly seem to treat and approach such virtual goods in the ways we normally treat and approach meatspace property. Is that correct?

READ: Yochai Benkler, There Is No Spoon, The State of Play: Law and Virtual Worlds, Jack M. Balkin and Beth Smone Noveck, Eds. (available at: http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/jbalkin/telecom/yochaibenkerthereisnospoon.pdf).

Do you agree with the implication in Benkler’s article that the “goods” in virtual property are better understood as avatars/platforms for social relations and interactions than as “property”, so to speak? Is this a question that should be addressed to the “engineers who design game platforms and to their business managers or marketers” rather than to “judges or regulators”?

III. “Private” Law and Virtual Property

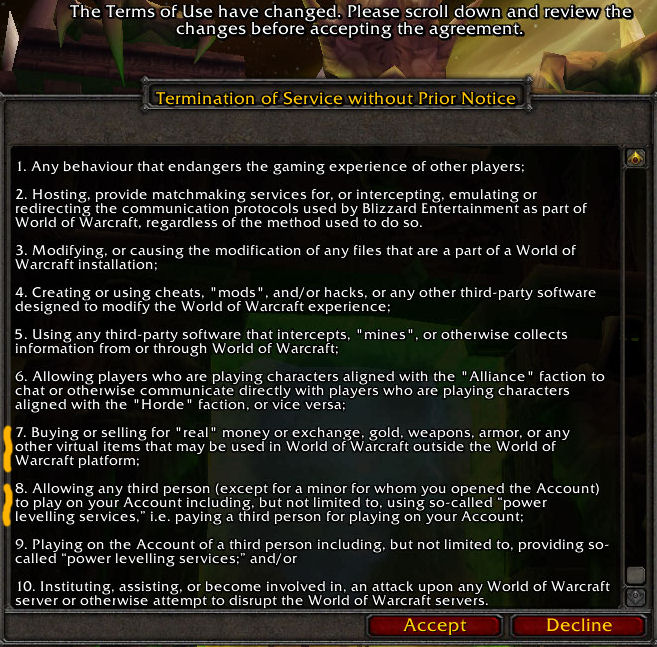

Benkler notwithstanding, the progress of contract and licensing law governance of virtual property has been pretty uniform: the “property” earned or submitted to such online games and communities is licensed, not owned, and severely limited in what the players can do with it. Nearly every online game requires agreement to click-wrap Terms of Service and End User License Agreements for access to the “services” the developer provides and the servers the game runs on. Any “virtual property” rights are limited by the terms of such agreements.

Courts have fairly consistently found click-wrap ToSs and EULAs valid and enforceable:

READ Evans v. Linden Research, Inc., 763 F.Supp.2d 735 (E.D. Pa. 2011) (available at http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=17398663132717127254).

Evans applied a contract-law unconscionability standard to a forum selection clause in Second Life’s ToS, and found the clause enforceable. Is unconscionability the right standard to apply to click-wrap license clauses regarding property ownership?

The Evans court distinguished “mandatory” forum selection clause from those which offer a number of choices. Is that a valid means of distinguishing enforceable from non-enforceable click-wrap license clauses?

I have excerpted below a few relevant EULAs and ToSs from various online games:

Blizzard’s World of Warcraft EULA (Full document available at: http://us.blizzard.com/en-us/company/legal/wow_eula.html) (emphasis added):

|

Notice the distinction between the “Service” and the “Game.” When a player purchases a copy of the Game (typically for around $50.00), do they own that game? Is that game even usable without the “Service”?

Linden Lab’s ToS for Second Life (Full document available at: http://lindenlab.com/tos) (emphasis added):

User Content

|

Is the distinction between the specifically permitted uses of Linden In-World Content “solely in-World” and the specifically prohibited uses of Linden In-World Content “outside the virtual world environment of the Service” a logical one? What is Linden trying to preserve for itself? What kind of behavior is it trying to prohibit?

The Linden ToS grants that Users own the Intellectual Property rights for User Content. Do they “own” such content in a non-intellectual property sense? Do the User Content IP ownership policies conflict at all with the In-World Content policies?

Valve’s Steam Subscriber EULA provisions for user-created items (Full document available at: http://store.steampowered.com/subscriber_agreement/) (emphasis added):

|

F. Ownership of Software

|

|

Trading and Sales of Subscriptions Between Subscribers

|

|

Content Uploaded to the Steam Workshop

|

Notice what you can do with an “item” in the Valve Marketplace: you can trade, sell, or purchase it, and you have to pay the taxes on those sales. It appears that you still own the intellectual property rights to the item, and may remove it from the Valve Marketplace at your discretion. Yet, as far as it exists in the game (and it can only be used in the game), you still do not “own” it.

Should developer-created items and user-created items be treated the same way when it comes to click-wrap licensing agreements?

IV. Judicial Review of Virtual Property

READ: Jacqui Cheng, Second lawsuit over purloined naughty bits settled, Ars Technica (March 26, 2008) (available at: http://arstechnica.com/gaming/2008/03/second-life-lawsuit-over-purloined-naughty-bits-settled/).

Ultimately what is being treated as “property” are computer scripts and codes. Copying such codes is far easier than copying a physical object. Is property law well-equipped to handle this difference, regardless of how those codes are treated by their creators, buyers, and sellers?

READ: Bragg v. Linden Research Inc., 487 F.Supp.2d 593 (E.D. Penn. 2007) – Sections I: “Background”, and II: “Motion to Dismiss for Lack of Personal Jurisdiction” (ONLY up to page *602) (available at http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=583434033289222111). Note particularly the Court’s focus on the “virtual town hall meetings” held in the Second Life game regarding ownership of “virtual property.”

Does it make sense to apply “real world” personal jurisdiction based on “virtual” representations regarding “virtual” property? (N.B.: the Bragg case eventually settled out of court.)

V. The “Virtual Property” Approach and e-Books

The issue of e-book “ownership” has been achieving increasing attention, primarily when providers (such as Amazon) delete or limit access to purchased content.

READ: http://www.forbes.com/sites/suwcharmananderson/2012/10/23/amazon-ebooks-are-borrowed-not-bought/

E-books, by the terms of their license agreements, cannot be bought or sold the way truly virtual property can and often is. One of the hallmarks of traditional legal notions of property is the power to exclude. How “exclusive” are e-books or virtual property? Why do you think e-book ownership issues have received so much more attention than virtual property ownership issues?

LAW 897 Syllabus: http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jdlitman/classes/cyber/syllabus.html