Use the first and second links below to estimate your average monthly bandwidth usage and current bandwidth speed. For testing your speed, please do the test at least three times at different times of the day (for example, in the morning, after dinner, before you go to bed) and note any significant differences. While reading, refer to your own usage patterns and think about how your usage would/wouldn't be affected (Do you think you'll still be using the same amount five years from now? The same speed?). The third link is included for optional use.

Quick-and-Dirty Technical Reference

Bandwidth: The maximum amount of data (measured in bits) that can travel along a connection in a given time (usually measured in seconds), or in other words, a maximum rate of transfer. The usual analogy is "pipes." High bandwidth is like a wide pipe, which lets a lot of water flow through it. Low bandwidth is like a narrow pipe, which lets less water flow through. If you try to force more water through a pipe than it can accommodate, bad things like pipe breakages and backups (slower or dropped connections) happen.

| High bandwidth = wide pipe | Low bandwidth = narrow pipe |

|

|

There is one crucial difference you should keep in mind: pipes tend to be one-way, but Internet connections are two-way - your computer both sends and receives information over its connection. A two-lane highway might be a better analogy, with too much traffic or road construction paralleling connection congestion, but the pipes metaphor has almost become a term of art in the net neutrality debate, in large part due to AT&T CEO Edward Whitacre's infamous outburst in 2005 (reading this is optional).

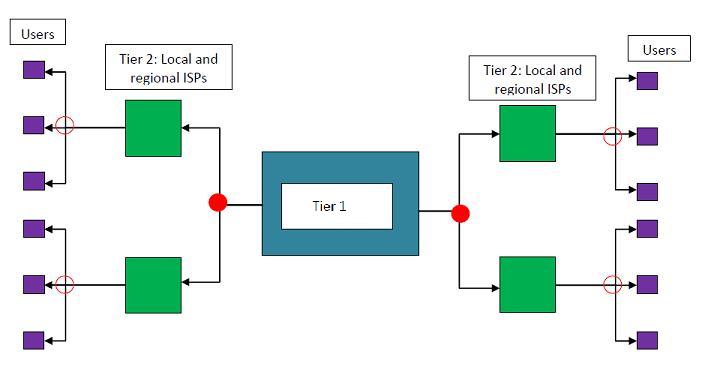

Infrastructure: We often talk about the Internet as one network, but it's actually a system of interconnected networks joined by routers, which receive and pass along packets of information to the correct connection. Have a crude graphic.

In simplified terms, Tier 1 companies own and administer the "backbone" of the Internet, very large networks of a few very high-bandwidth connections. Tier 2 companies own and administer smaller, regional or local networks with many lower-bandwidth connections that connect users to the backbone networks. A Tier 2 company often has to pay Tier 1 companies for connection to the backbone networks, which allows its customers access to networks beyond its own network. Tier 1 companies may also directly connect to users, so something to keep in mind is that Tier 1 and 2 companies are mainly differentiated by whether or not they have to pay to connect to other networks, not by whether they directly connect to the user. However, the Tier 1/Tier 2 distinction is blurry, in part because it is difficult to get ISPs to disclose their connection agreements with each other. Tier 2 companies can be subsidiaries or affiliates of the Tier 1 company they pay for network access, or they can be in direct competition with Tier 1 companies for user subscriptions.

There are also smaller ISPs ("Tier 3," not shown) who don't own their own networks and instead "rent" bandwidth from Tier 2 or Tier 1 companies and then resell it to users. Tier 3 companies can be in competition with Tier 1 and/or Tier 2 companies, or they can be affiliates and subsidiaries.

Since Tier 3 companies do not own networks, they have little control over changes in bandwidth. Tier 2 companies can control bandwidth on their networks, but cannot control bandwidth or access to the backbone networks (open red circles = Tier 2 control points). Tier 1 companies have an enormous amount of control over bandwidth and network access, since they connect smaller networks to each other (closed red circles = Tier 1 control points). Without backbone networks, the Internet would fragment into hundreds of smaller networks that would all be unable to access each other.

Optional: This article has more information on Internet infrastructure, if you'd like to learn more or if the graphic isn't helpful. Another useful explanation can be found in this paper, *1577-*1586.

What Net(work) Neutrality is: Read these two links for an overview.

One major battleground in the network neutrality debate is how well the current network infrastructure handles bandwidth demands. The anti-network-neutrality group argues that the hardware infrastructure of the Internet is growing increasingly overloaded and congested by high-bandwidth uses, so network management is necessary in order to keep the networks working and to fund network upgrades to support the increased usage. The pro-network neutrality argues that the congestion fear is over-exaggerated, so allowing network management methods that discriminate based on content would harm the Internet more than it would help.

Follow the reading instructions for each subpart, focusing on the congestion argument.

Opinions: Currently the U.S. has no laws on network neutrality, but the FCC has issued and enforced a Broadband Policy Statement that outlines a pro-network neutrality stance. Read the FCC Policy Statement and at least two of the other links.

FCC policy statement from In Re: Broadband Access

Debates: Read both.

How do you know how much work an ISP is doing its infrastructure rollout and upgrades? How "busy" its network is? Information on these questions is hard to come by, but at least one firm is trying to make a business of collecting such data and analyzing it. Read this brief summary of Telegeography's latest study and then spend some time browsing Telegeography's free resources. If you don't want to register, try Bugmenot.com.

Unlike the FCC in the U.S., the relevant Canadian government agencies have been relatively slow to adopt a position on network neutrality1. The major U.S. telecommunications companies have--at least publicly, and for the near future-agreed to avoid non-neutral network tactics designed to disadvantage customers of their rivals, but Bell Canada, Canada's largest telecommunications company, has publicly adopted a policy of deliberately slowing some user connections. Furthermore, they have defended their position against the public outcry and appear to be continuing this policy even as the Canadian Radio and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) reviews the case. Read the below links to get up to speed.

1. This is partly due to the CRTC's apparent belief that it doesn't have strong regulatory powers in this area. The FCC, on the other hand, has consistently attempted to take a central role in occupying the field of telecomm regulation.

Read these links on bandwidth caps. Consider: are they a good compromise between ISPs and Internet users? On what basis (economics, Internet rights, etc.)? Do they violate network neutrality?

Go to the syllabus.