Areas of Interest

My areas of interest span a wide range of the literature, art, and culture of nineteenth-century France: poetry, the novel, and autobiography; art criticism, aesthetics, and the relations between the arts; the city, Walter Benjamin, and the history of modernity; the representation and writing of history; parody, caricature and the comic; painting and early photography; Romanticism, Realism, and Decadence; the Mediterranean. For many years my work focused on the writings of the French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix, culminating in a major new edition of his journals, published in French in 2009. I have worked extensively on Delacroix's trip to the Maghreb and southern Spain in 1832, and have brought out a translation into English of his writings on it. I have a strong interest in the Mediterranean as a space of exchange and interaction and have published a number of articles on early photography in the eastern Mediterranean. A book on the relation between the writing of art and the writing of history in the work of the Romantic historian Jules Michelet came out in 2019.

- Parody and Laforgue

- Baudelaire, Caricature, Benjamin, and the History of Modernity

- Delacroix's Aesthetics

- The Edition of Delacroix's Journal

- Further Work on Delacroix

- Updates to the 2009 Journal

- Translation of the Journal into English

- Notebooks from the Maghreb trip

- Nineteenth-Century Photography

- Trials

- The Mediterranean

- Michelet

Although my training was in French and Comparative Literature, I became interested early on in the visual arts through my dissertation research on the poet Jules Laforgue (1860-1887). In his short life, Laforgue wrote a substantial body of radically experimental poetry which was the first to use free verse and was extremely influential on the later generation of Modernist poets, particularly T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound. In addition, Laforgue was a highly original art critic and one of the first theorists of Impressionism. My first book, Parody and Decadence. Laforgue's Moralités légendaires (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1989), dealt with his last work, the Moralités légendaires (1887), an enormously innovative collection of tales in which he parodied late nineteenth-century Decadence by using famous stories from the literary canon. I used the Moralités to formulate a theory of parody as a creative, rather than a derivative, form and as an engine of the avant-garde. Parody and Decadence was reissued in paperback in 2016. Alongside this work on Laforgue's literary œuvre, I wrote a number of articles on his art criticism and theory.

Baudelaire, Caricature, Benjamin, and the History of Modernity

These two currents -- parody and art criticism -- led me to my next project on the poet Charles Baudelaire's three essays on caricature and the comic: De l'essence du rire et généralement du comique dans les arts plastiques (1855), Quelques Caricaturistes français and Quelques Caricaturistes étrangers (1857). I was interested in how these essays related to Baudelaire's seminal theory of modernity, which has become the point of reference for ideas of modernity and even postmodernity ever since. I argued that these essays developed not only an aesthetic of caricature as an art in its own right, but also a caricatural aesthetic which defines the art of modern life. In particular, Baudelaire's theory of the comic as dual and ambiguous, implicating the person who laughs in his or her own laughter, had important consequences for such emblems of modernity as the city and the flâneur. I showed that, for Baudelaire, the modern city is the space of the comic -- the ironic and grotesque --, presenting urban flâneurs with an image of their own dualism, their position as subject and object, subject to the same experience they seem to control, an idea which Walter Benjamin would later develop in his work on Second Empire Paris.

Writing this book, I began to work seriously on Benjamin, whose lifelong fascination with Baudelaire had resulted not only in several essays on the poet but also in his unfinished magnum opus on the history of modernity, Das Passagen-Werk (The Arcades Project). I became particularly interested in the figure of the caricaturist J.J. Grandville (1803-1847), whom Baudelaire discusses in Quelques Caricaturistes français and who was one of Benjamin's most consistent references in the Arcades Project. In my article "The Allegorical Artist and the Crises of History: Benjamin, Grandville, Baudelaire" (click here to download), I argued that Grandville stands behind Benjamin's important theory of allegory as a modern form, one that both embodies and lays bare the fantasmagorias of modern life -- the illusory façade constructed by ideology to hide the true state of human beings under a regime of capital.

Delacroix's aesthetics

While writing my book on Baudelaire, I went to check an episode in Delacroix's Journal in which Delacroix records Baudelaire's visit to his studio in 1849. I had never read the Journal, and I expected just to be dipping into it for this one episode. As it turned out, I found the Journal fascinating and read the whole work. Kept briefly during Delacroix's youth from 1822 to 1824, and then steadily from 1847 until his death in 1863, the Journal is one of the most important works in the literature of art history: a masterpiece of art criticism of the stature of the Salons of Diderot and Baudelaire, and one of a highly select group of artists' writings that include the sonnets of Michelangelo, the notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, the Discourses of Joshua Reynolds and, later, the letters of Vincent Van Gogh. Delacroix discusses the various arts -- literature, painting, opera, architecture, music, drama, photography; he reviews performances he attended, often several per week; he notes his thoughts on other artists and techniques past and present, as well as his own work; he uses it to draft his never-completed treatise on the fine arts, the Dictionnaire des Beaux-Arts, with entries ranging alphabetically from "academy" to "varnish", and on subjects as diverse as "distraction" and "daguerreotype." In addition to its aesthetic value, the diary also constitutes a work of extraordinary socio-historical interest, furnishing an ongoing commentary on the culture of nineteenth-century France, unequalled in the stupendous range of personalities, events, and issues that run through its pages. Delacroix was in close contact not only with all the major artists of his time, but also with all the major figures in French cultural and political life from the Restoration through the Second Empire. In recording the painter's daily activities and thoughts, from small details to momentous events, from practical information to theoretical abstraction, the diary provides a unique perspective on a society undergoing the rapid and sometimes tumultuous changes of modern life, viewed through the eyes of an individual who experienced them first-hand and reflected on them at length.

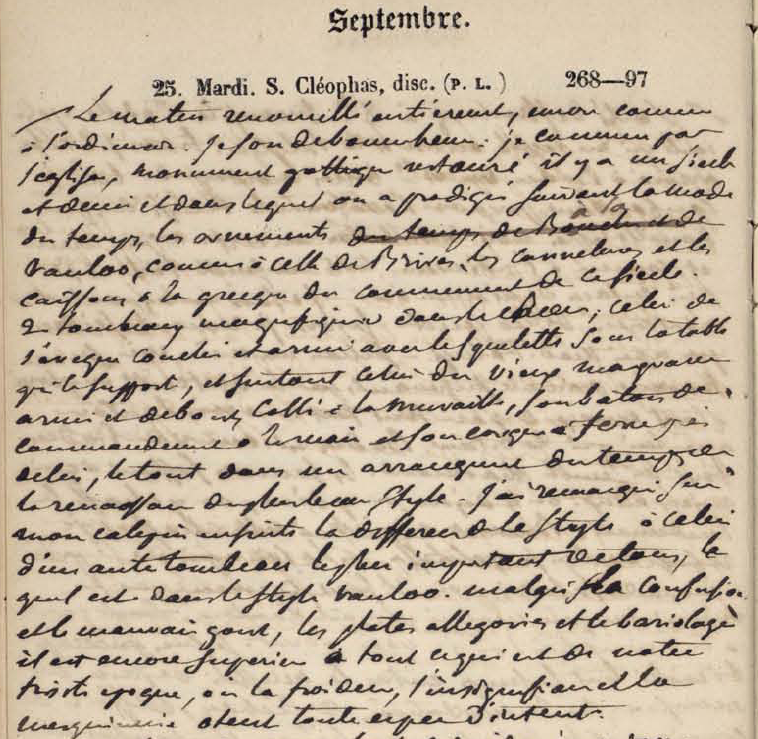

(an entry from the Journal, dated September 26, 1855)

I was especially struck by Delacroix's theorization of the relations (and differences) between painting and literature, image and text, and in his self-reflexive commentary on his own writing. I thought about what this attention to writing might mean for a painter whose pictorial œuvre was dominated by literary subjects and by narrative paintings, including decorative cycles. This resulted in my third book, Painting and the Journal of Eugène Delacroix (1995), in which I examined the importance of the text-image relationship for Delacroix's aesthetic theory and artistic practice. I argued that, through the Journal, he sought to develop a painter's writing, a writing proper to painting, and that such writing also reflects his own conception of painting. In chapters dedicated to his writing (the Journal, the unfinished Dictionnaire des beaux-arts) and to his narrative cycles (the libraries of the Palais Bourbon and the Luxembourg palace, the Apollo Gallery of the Louvre, the Chapel of the Holy Angels in the church of Saint-Sulpice), I attempted to show that, in the experimental writing of the Journal, Delacroix infused the space of writing with the qualities of painting, and in turn infused his narrative painting with the special temporality of the Journal's writing.

The Edition of Delacroix's Journal

While working on this latter project, I went to Paris to consult the original manuscripts of the diary, as numerous non-sequiturs and inconsistencies in the standard edition of 1932 had led me to question its reliability. There I indeed discovered that this edition, then accepted as definitive, left out much material and contained many errors. Absent from the published version were hundreds of jottings on the inside covers, lists of names and addresses of suppliers, clients, friends and acquaintances, fragments of letters, color formulas, pages of notes and quotations from Delacroix's readings, and numerous cross-references between diary entries; clippings from the daily newspapers (articles, advertisements, notices, reviews) were interleaved among the pages, along with recipes, addresses, train schedules, accounts and investments, notes for his work on the many public committees on which he served, and other such "paraphernalia", discreet fragments of nineteenth-century life alongside the more explicit and sustained reflections of the Journal. Moreover, innumerable mistaken readings in the standard edition greatly affected the sense: it printed "Raffet", a minor nineteenth-century artist, instead of "Rossini", the great composer; "œil" instead of "art"; "plans" instead of "fleurs"; "politique" for "poétique"; "suis" for "jouis"; "matière" for "manière"; "reçu" for "revu"; "popularité" for "postérité"; "opinions" for "origines"; "instruction" for "invention", and so on. Perhaps even more important, the published version frequently altered the order of the entries to conform to the traditional chronological temporality of a diary. In fact, Delacroix reread his old diaries constantly and commented on them as he did so, dating the comment accordingly; any given entry might therefore contain notes from several dates distant in time, all on a single subject or related themes. In the standard edition, these "subsequent" notes had been separated out and put in their chronological place instead, which changed the meaning completely, sometimes making the entry nonsensical.

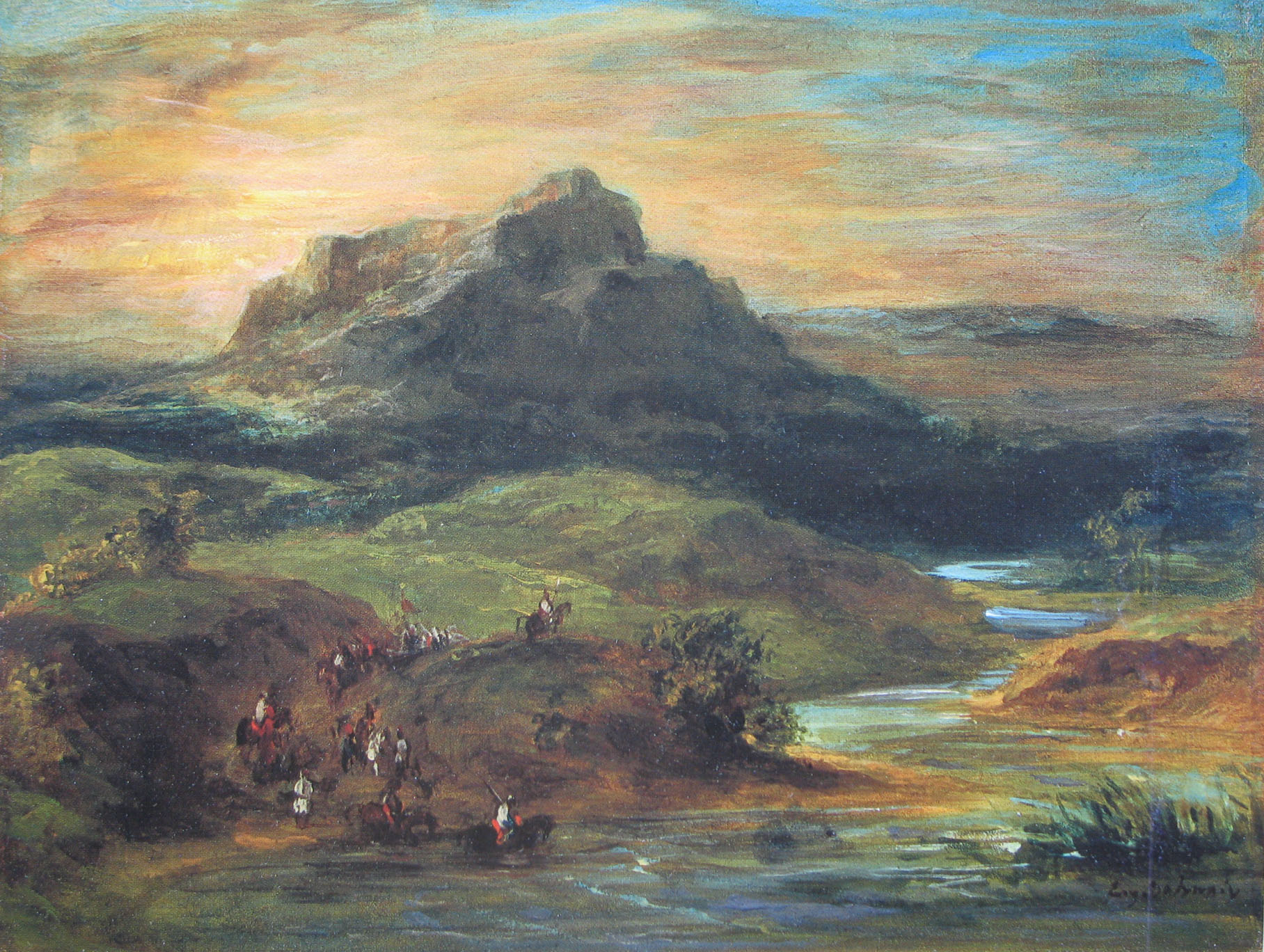

I thus undertook to produce a new scholarly and critical edition of the Journal, based on the original manuscripts. This was a considerable task even in its initial conception, but it grew enormously in 1996, when I discovered the papers which had been in Delacroix's studio when he died. These were still with the descendants of his heir, who were largely unaware of what they were. The archive contained hundreds of pages of manuscripts, notes, letters addressed to Delacroix, household accounts, bills and receipts, legal documents, and the like. One of the most interesting pieces was the draft of an article, which Delacroix never published, on his journey to North Africa in 1832. This fascinating text, written ten years later, provides a rather different picture of Delacroix's Orientalism from the standard one, a fuller and more complex account which includes a harsh critique of the "barbarism" of the supposedly civilizing conquest of Algiers (see Journal I, 283-285). The archive also contained a painting which had not been seen since 1885 and was considered lost (reproduced below). (I recount the story of this discovery, which has a bit of the detective novel to it, in my article of 2010, "Histoire d'une édition: le Journal de Delacroix, archéologie et reconstitution d'un document." Click here to download.) I incorporated all this material, as well as other smaller archives, which turned up later, into the new edition. This was published in 2 volumes in 2009 (http://www.jose-corti.fr/titresromantiques/JournalDelacroix.html). I was interviewed about the edition on France Culture's "Du jour au lendemain" (click here to download.). For some reviews of this edition of the Journal, click here: David O'Brien, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide. Beth Wright, H-France. Julian Barnes, TLS. Jon Whiteley Burlington Magazine. Further reviews can be found under "Publications."

(Delacroix, Moroccan Landscape, 1855)Further Work on Delacroix

Since publishing the Journal, I have continued to work on elements of it that I had not resolved or been able to develop fully in the publication. One of the most amusing of these was the identity of a woman with whom Delacroix was romantically involved in 1824 and who occupies much of the Journal for that year. As Delacroix refers to her simply as "J.," her identity had remained unknown. I had surmised, on internal evidence, that she might be Louise de Pron, a well-connected aristocrat who was married and had a son, but I had been unable to prove it; I had even found in the Getty Research Institute a number of letters from "J." to Delacroix, but as they were not signed, I could not tell who their author actually was. One day I was contacted by a Frenchwoman who was living in the château that had belonged to Mme de Pron, and who had found a copy of her autograph will. Comparing it to the letters which I had found, we saw that the handwriting matched exactly; the mystery of "J." was thus solved. We wrote an article jointly on Delacroix, Mme de Pron and a series of related paintings, including Delacroix's Still Life with Lobsters and some extraordinary paintings, not by Delacroix but integral to the story, which decorate the walls of the château. (See "Delacroix, 'J.' and 'Still Life with Lobsters.'" Click here to download.)

(Camille Bonnard, Military Costume, from Costumes

des XIIIe, XIVe et XVe siècles, Rome, 1828, vol. I, pl. 20.)

Another offshoot of my work on Delacroix had to do with the diary of an anonymous painter who was in Florence in 1821 where, as the author records, he was in close touch with Ingres. This diary had been published in 1972 but the painter's identity had remained unknown. Using a chance connection with Delacroix, I identified the painter with certainty as Camille Bonnard (1794-1870), who turned out to have been enormously influential on many of the history and genre painters of the nineteenth century, especially the British Pre-Raphaelites. His publication on medieval costume, Costumes des XIIIe, XIVe et XVe siècles (1828), was consulted, copied, and used as a source by painters such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, Ford Madox Brown, Edward Burne-Jones, Paul Delaroche, Ary Scheffer, and Pierre-Henri Révoil. In addition, Ingres seems to have done portrait drawings of several members of Bonnard's family, including Bonnard himself: see Publications and http://burlington.org.uk/magazine/back-issues/2008/200805/.

Having come across many unknown letters over the course of my work on Delacroix, I also published, with Lee Johnson, a volume of previously unpublished letters (see Eugène Delacroix. Nouvelles Lettres, 2000).

Updates to the 2009 Journal

I have been compiling a list of addenda and corrigenda to the 2009 edition of the Journal. This is available through the University of Michigan's "Deep Blue" archive (click here). It contains new material which has come to light since the 2009 publication, corrections of mistakes, clarifications, the results of new research and the like. This will be updated periodically.

Translation of the Journal into English

I am currently translating the Journal into English. The Journal has never been translated into English in its entirety; selections were published in 1937 and 1951, but these represent only a fraction of the whole. With the publication of the 2009 edition, with its corrections and vastly expanded corpus of Delacroix's writings, the need for a new, complete translation, became necessary.

The first tranche of this translation, Journey to the Maghreb and Andalusia, 1832, appeared in 2019.

Notebooks from the Maghreb Trip

By a happy coincidence, two previously unlocated notebooks from Delacroix's journey to Morocco and Spain turned up in 2018. I am currently working on a publication of these. In addition, I am preparing a fac-simile edition of the other notebooks for a French publisher.

Nineteenth-Century Photography

Working on nineteenth-century art criticism, autobiography, and painting led me to the work of Théophile Silvestre, a prominent art critic under the Second Empire and friend of Baudelaire's. In 1853, Silvestre launched a major series of biographies of living artists accompanied by photographs of their paintings. He aimed to offer a new type of biography which, like the images, would be "photographic": the biographies were meant to give the reader "direct" access to the artist by quoting the artist's own words -- journals, letters, interviews, etc. --, just as the photographs gave "direct" access to the paintings, without the intervention of an engraver. This was the first publication ever to reproduce contemporary paintings though photographs. The project ultimately failed and Silvestre ended up publishing a smaller, less expensive and less innovative version without photographs, but fragments of the original project exist. I reconstructed the project from the available evidence, analyzed its theoretical ambitions and practical achievement, and discussed the questions that it raised about authorship and (self-)representation under the new regime of photography. These issues were brought out spectacularly when Silvestre was successfully sued by the painter Horace Vernet for unauthorized reproduction of his private correspondence, in a trial which proved to be important for the direction art criticism would subsequently take. See Publications: "Théophile Silvestre's Histoire des artistes vivants: Art Criticism and Photography." Click here to download.

I also became interested in early photography of and in the Mediterranean (see below and Publications).

Trials

I have always been interested in trials of literary and artistic works, for I believe that they provide a unique occasion to observe a society's practices of interpretation and criteria of judgment in action. The social issues in such trials -- sedition, blasphemy, obscenity, libel -- are fundamentally related to questions of interpretation, which account for the different readings of the prosecution, defense, witnesses, judges and jury, and on which the conviction or acquittal will depend. Nineteenth-century France had some of the most spectacular trials of works of literature and visual art in the modern era -- Daumier's caricatures and Philipon's "Poire," Flaubert's Madame Bovary and Baudelaire's Fleurs du mal, among others. In 2011 I published an article on the trial of the Fleurs du mal in which I argued that Baudelaire's trial and conviction were based on some legal and interpretative principles which were highly unorthodox at the time, and which, ironically, reflect a kind of reading that we now call "modern." (See "Reading the Trial of the Fleurs du mal." Click here to download.)

The Mediterranean

In the wake of my work on Orientalism and on Delacroix's journey to the Maghreb, I became interested in the Mediterranean as a space of cultural interaction and exchange, even from within a colonial context. The invention of the daguerreotype in 1839 set off a veritable spate of photographic expeditions to the Middle East and North Africa by European travellers. But photography soon took hold in the major cities of this region themselves, as local photographic studios sprang up in cities such as Cairo, Alexandria, Beirut, Jerusalem, Damascus, Istanbul, and Athens. In addition to European travellers and local practitioners, there were European photographers who settled in these places, and photographers of Middle Eastern origin who travelled to other cities in the region and beyond. I am interested in what this complex picture, and the circulation of photographs and photographers in the Mediterranean more generally, can do to our understanding of "Orientalist" photography. This resulted in several articles. The first, published in two parts, was "Horace's Vernet's 'Orient,'" on the painter Horace Vernet's journey to Egypt and the Levant in 1839, during which he and his compantion traveller took the first ever daguerreotypes of the region (click here to download). (For Part II, click here to download.)

The second article, "Practices of Photography: Circulation and Mobility in the Nineteenth-Century Mediterranean," examined the Mediterranean context of early photography, located within a space of multiple languages, ethnicities, and religions, of personal and commercial networks between cities and across borders, and of spatial and social circulation and connectivity. I discuss the ways in which photography in the Mediterranean was practiced, used, received, and consumed, and what this may reveal of the social, religious, ethnic, and linguistic variety of this region, the degree of interaction or separation between groups, and the ways in which identities were represented, affirmed or complicated in a period of transition, transformation, and modernization (click here to download).

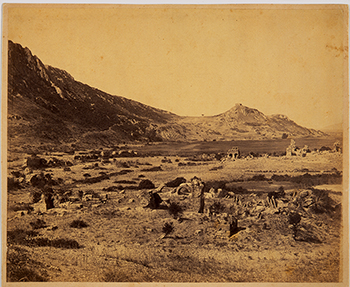

The third article, "The Art of Wandering: Alexander Svoboda and Photography in the Nineteenth-Century," deals with the painter and photographer Alexander Svoboda (1826-1896) as an emblematic example of the mobility of early photography in the "greater Mediterranean." Born in Baghdad, Svoboda trained as a painter, learned photography in Bombay (modern Mumbai), opened a photographic studio in Smyrna (Izmir), later settled in London, and at the end of his life moved back to the East. He was the first to photograph important archaeological sites such as the Hindu caves at Elephanta, places in Iraq such as the royal palace at Ctesiphon (Taq Kesra) and the so-called shrine of the Prophet Jonah at Nebi Yunus near Mosul, and all the major sites of western Anatolia (Smyrna, Ephesus, Laodicea, Philadelphia, Sardis, Thyatira, Pergamos, Magnesia of the Meander, Magnesia of Mount Sipylus, Hierapolis, Aphrodisias, Aidin, the Karabel relief, and the "Niobe" rock formation on Mt. Sipylus). He later published some of these latter photographs, along with commentary, in a book, The Seven Churches of Asia (London, 1869).

(Alexander Svoboda, Ephesus. General View Looking Toward the Sea. Prison of St Paul on the Hill, 1866. Albumen silver print, 22.1 x 27.1 cm. Photo: Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, 92.R.84

Michelet

My recent book, Jules Michelet. Writing Art and History in Nineteenth-Century France (Penn State, 2019), deals with the relation between the writing of art and the writing of history in nineteenth-century France, focusing on the work of the Romantic historian Jules Michelet (1798-1874). Michelet was a prolific and insightful writer on the visual arts, and his conception of historiography accorded to them a major place: he treated works of painting, sculpture, architecture, and engraving as historical phenomena to be considered as historical evidence. As I argue, however, the visual arts did not simply fill in an incomplete historical picture; rather, they were a key site, and vehicle, for the interrogation of history in all its complexity, leading Michelet to the formulation of his most important historical concepts, such as the Gothic, the Renaissance, civil war, nation and the people. Moreover I argue that, in its style, Michelet's art-writing reflects a concept of history in which past and present are integrally bound in a hermeneutic dialogue. This use of art-works as allegories of the historian's relation to, and writing of, the past prefigures the practice of modern philosophers of history such as Michel Foucault and Michel de Certeau.