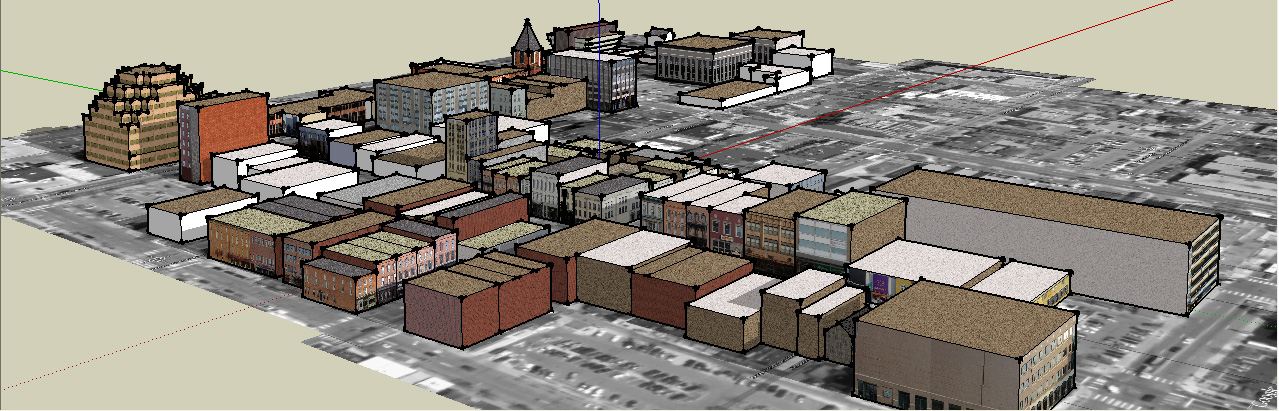

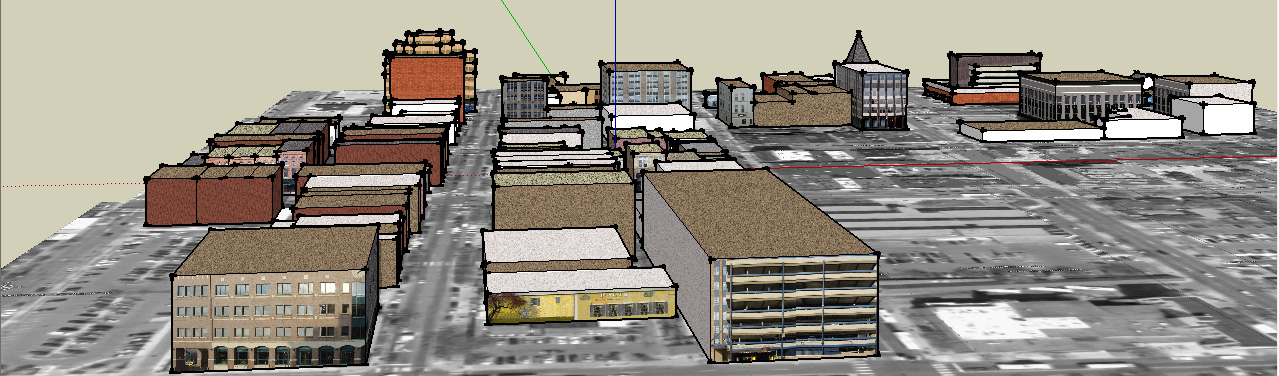

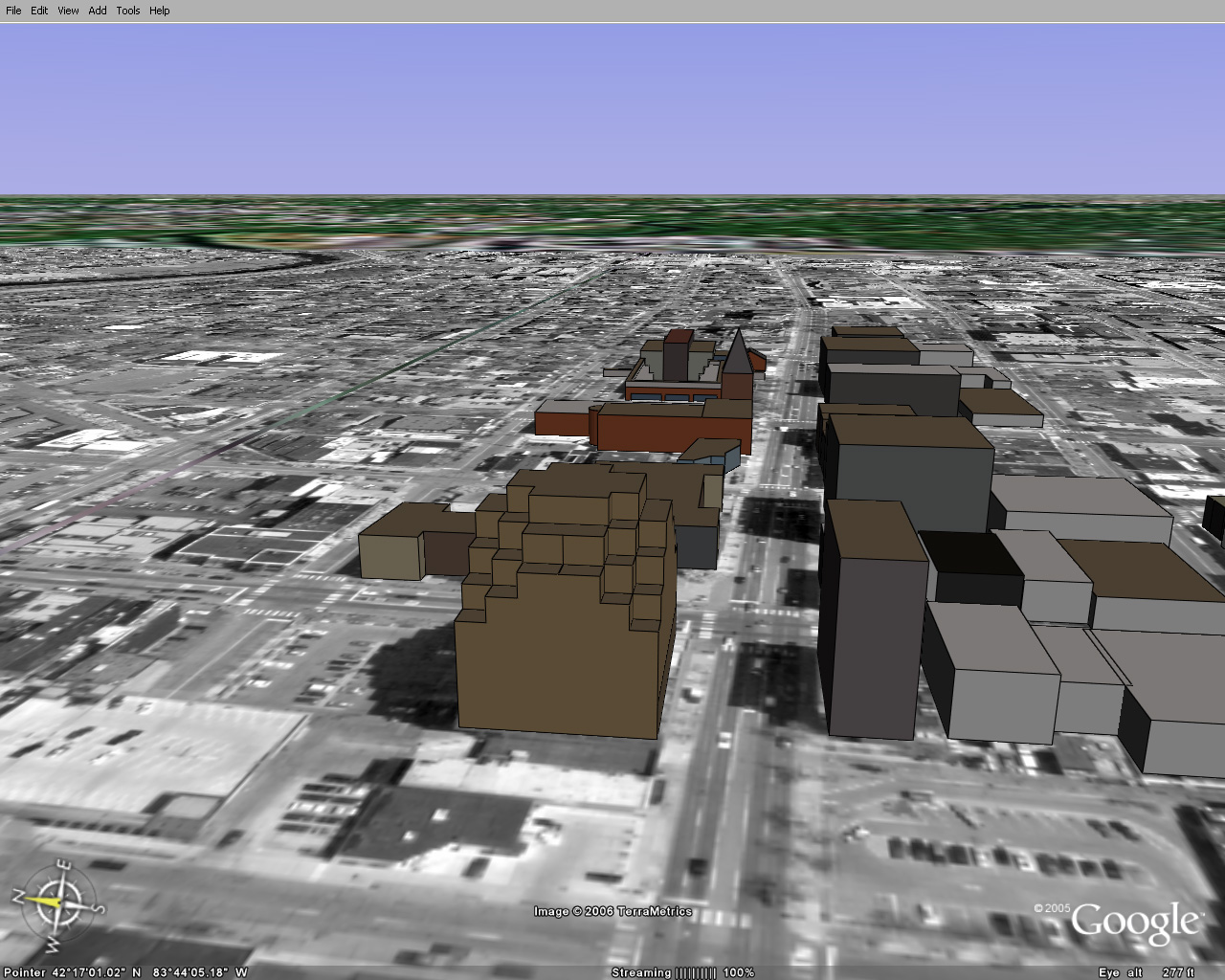

The images in Figures 1 to 8 are

all based on screen captures from

interactive products. As such, they present only a small part of

the

story. To see the Ann Arbor files, in Google Earth®, download

Google

Earth®

to your hard drive. Save the following files to your desktop

(scanned by Norton and virus-free at upload):

Then, in Google Earth®,

go to Open and navigate to the files on your

desktop and open each of the three. Then, type in "Ann Arbor" and

you

should be able to navigate the buildings for yourself! Notice the

compass. |

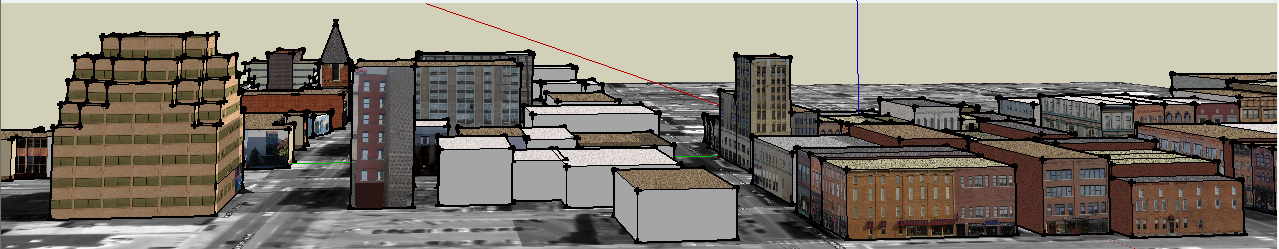

If you wish to view the scene

with the photographic textures and

shadows at varying positions, or to add new buildings of your own as an

experiment in planning, then download Google SketchUp® (link

below with the

library of textures used) and install it and also download the SketchUp®

file and Open it in SketchUp®.

- SketchUp®

executable file with suitable library: Link 4.

- SketchUp®

file of Ann Arbor: Link 5.

|

During the past 6 months

presentations of the 3D Atlas of Ann

Arbor,

1st Volume (without Google Earth/SketchUp®), were

given by the author

to various groups of community leaders. Particular wishes, beyond

what

was presented in that material were:

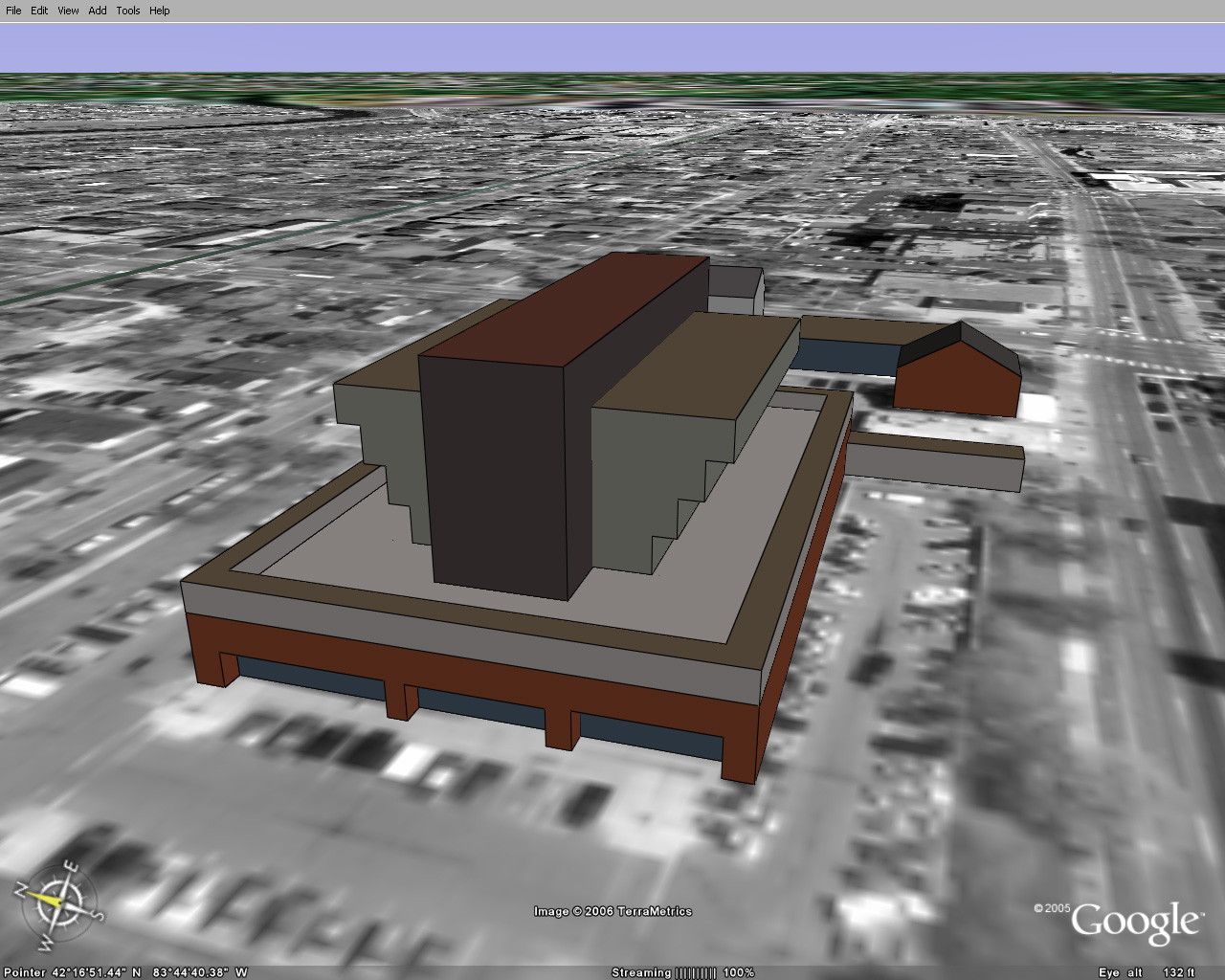

- a desire to model buildings

- a desire to introduce detail at the level of a single

building

(awnings, window displays, design elements of the building, and so

forth)

- a desire to measure the effect of shadows

- a desire to be able to add buildings oneself, in

considering possible sites for future buildings

- a desire to build an Ann Arbor game

- a desire to be able to own easy-to-use software and do all

of the

modeling on a home computer, or a city council computer, with no

additional purchase of software.

The Google Earth/SketchUp®

package enabled the entire wish list. It is

an important tool to add to the glittering array of software already

employed by many urban and environmental

planners. |

What remains, beyond the obvious

(but time-consuming) completion of all buildings and field-checking of

heights and facades, is:

- to integrate the effect of terrain

- to learn to transform the files into a format that will

play out in an immersion CAVE or other interesting 3D visualizations.

|