LaripS.com, © Bradley Lehman, 2005-22, all rights reserved. All musical/historical analysis here on the LaripS.com web site is the personal opinion of the author, as a researcher of historical temperaments and a performer of Bach's music. "Bach-style keyboard tuning"Article by Mark Lindley and Ibo Ortgies, November 2006 issue of Early Music, published on the web as "advance access version October 3 2006".This is an eleven-page pre-print version, as a PDF file for download from Oxford's web site. (Subscription or library access are necessary to download this file (cal065v1); I am not at liberty to re-distribute it directly....) The final version was released here on November 10 2006, and in the printed issue as well; download from the Early Music web site. [2011: A free version is now available here through Stanford's "HighWire" service.] [Ortgies publications and web site (apparently released on approximately Nov 10 2006)] Here is the October version's abstract, as copied from that web site:

My initial remarks, October 2006:I will present a fuller response to this article after it appears in print with its final page numbers etc.At this point I'll simply start with a quick response to that abstract, and Oxford's "advance access" publication as PDF file. How do these authors presume to be inside my head, asserting what I allegedly "imagine" and "believe", and planting onto me the "outlandish" idea that "Bach's secret tuning is uniquely beautiful for music by Frescobaldi et al" (which of course I've not said, and don't believe...)? On the way to labelling my work as "daft"? Well, four additional pages of my comments are already drafted, to deal with such problems. Their article in general tilts at a series of straw-man windmills against my article: imputing to me a series of "implicit premises" that I didn't say and don't necessarily believe (at least in the overstated way they present my alleged ideas!), and then proposing to knock them down as "weak links". They recycle some of my reasoned (and I hope, carefully demonstrated!) conclusions from the musical evidence as if those were premises, thereby mis-representing the developmental direction of my arguments.... We'll come back to all that. Drs Lindley and Ortgies discard Bach's WTC title-page drawing as non-evidence, but only after they've asserted it's a "daft" pursuit altogether; and they do this in a context of presenting several other speculative temperament-interpretations of the same drawing. Are those other ones equally daft, more daft, less daft than mine; and how is such a level of alleged daftness to be judged objectively? Their point, obviously, is that all such speculation isn't reasonably reliable enough to them within their own historical and musical epistemology...but then they violate their own game, going on in this article to present a "Bach-style" speculative temperament of their own devising, with no documentary evidence, and no supported arguments describing the process by which they've concocted it! We'll come back to that, too. The authors even try to dismiss Bach's extant music as non-evidence (or at least as insufficiently reliable, as to performance practices), alleging that 18th century musicians didn't actually expect to play it. (And how do they know what 18th century people did not do, trying to "prove" that negative case?!...) They assert: "No extant documents from Bach's lifetime say that he (or anyone else) performed on an organ his written keyboard compositions; the reports of his playing refer apparently to improvisation." Does this constitute some manner of proof that Bach and everybody else did not use any of that extant music? And that we dare not, therefore, take any inferences whatsoever about keyboard-tuning practices, drawn from the actual music that survives from that milieu? Not even from play-throughs listening to Das wohltemperirte Clavier itself, the book that I put forth as primary evidence both musical and graphical? With all this evidence being kicked out the window, what are we to be left with? Dump all bathwater and all babies! All of which is to point out: my presentation, my writing style, and my consideration of evidence all do not fit into their paradigm...and Drs Lindley and Ortgies are then trying to disprove my work within that paradigm (rather than taking my work on its own terms, thinking outside their box). Incidentally, it was my observation of anomalies within that paradigm that got me seriously interested in this project, in early 2004, serving as what I felt to be a breakthrough: my sense that their paradigm happened to be untenable, because of the musical evidence that contradicts some of its points! The standard Lindley assertions, in print, about the sizes of major 3rds Db-F and Ab-C had already alerted me, for many years preceding, that something was possibly wrong with the historical paradigm as he and others have presented it. It sounded wrong to me, directly in the music; and I couldn't believe that nothing better (as to a euphonious result) was ever available to Bach's genius...why would Bach write ugly music with any horrible intervals in it? So, with tuning lever in hand and playing the music, I began to think and work outside the limitations of their methodologies: to see what else might be possible (and yet credible and reasonable, backed up with what I believe to be sufficiently hard evidence).

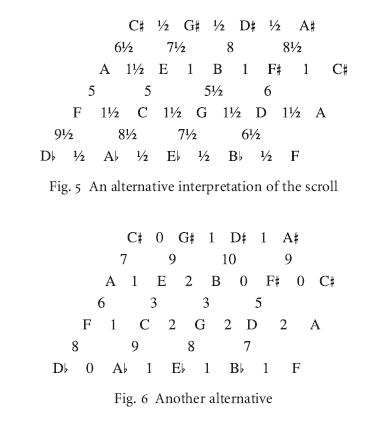

For now, some of the most immediately important remarks of mine are as follows, as the Lindley/Ortgies article contains a number of factual errors. Several of those look merely like typesetting/proofreading glitches, and scarcely affect their arguments. One of them, however, is a much profounder faux pas of omission on their part...and it's a straightforward example of discarding (or at least overlooking) important evidence, not tied to assessments of anyone's taste. First, the several numerical errors in their charts. My suggested corrections here are to ensure both the internal consistency within each chart (i.e. the sizes of 5ths are just plain wrong, according to the sizes of the 3rds!), and consistency with their explanation in the body of their article.

Now, on to the most serious error of omission. In one of the sections of their article, Lindley and Ortgies assert the following. The part in [brackets] here is their presumptive assertion (i.e. straw-man argumentation) against what they believe to be a premise of mine, and then it's followed by their assertive refutations:

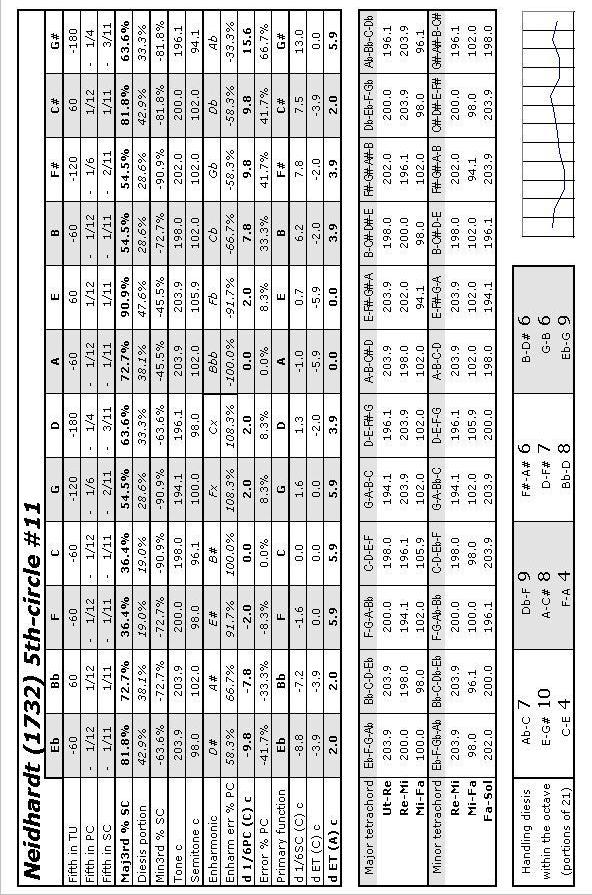

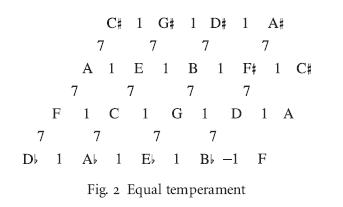

"[Significant documentary support for the claim that Bach always tempered E-G# by as much as shown in fig. 3 is to be found in some remarks by Sorge ...] Neither Sorge nor Neidhardt ever countenanced tempering E-G# (for any reason whatever) by as much as Dr Lehman says Bach always tempered it. Neidhardt would never countenance tempering E-G# more than Ab-C." "Ever?" (Whether in print or not...?) "For any reason whatever?" Strong statements. And, in their abstract it corresponds with this sentence of theirs: "No tuning-theorist close to Bach approved of tempering E-G# as much as Lehman does." Here's a simple counter-example in which Neidhardt did both these things, in print: making E-G# tempered as widely as mine, and making it wider than Ab-C. Without my further analytical comments yet at this point, this is one of Neidhardt's 21 example temperaments published in his 1732 treatise. (Neidhardt, Johann Georg. Gäntzlich erschöpfte, mathematische Abtheilungen des diatonisch-chromatischen, temperirten Canonis Monochordi, Königsberg and Leipzig 1732.) This musically interesting temperament with three slightly wide 5ths is #11 among the twelve "Quinten-Circuls" presented by Neidhardt as a set of charts. This is one of five(!) example temperaments in that Neidhardt treatise that each "countenance tempering E-G# by as much as" the E-G# in my presented hypothetical Bach temperament. Also, this one happens to have E-G# noticeably wider than Ab-C! Its 5ths are as follows, using Neidhardt's standard (and theoretically indivisible--to him and Sorge but not to Lindley!) units of 1/12 Pythagorean comma: C 1 G 2 D 3 A 1 E -1 B 1 F# 2 C# -1 G# 3 D# 1 Bb -1 F 1 C.

This chart is generated by the same spreadsheet I use for all of my larips.com analyses, for consistency. Look especially at the C-E-G#/Ab-C column at the bottom, showing the sizes of stacked major 3rds measured in 1/11 fragments of the syntonic comma -- the same unit of analytical measurement later used by Sorge, correcting/updating Neidhardt's own slightly incorrect 1/12 method of reckoning from this same 1732 document (and Neidhardt's 1724 treatise as well). Here in Neidhardt's 5th-circle temperament #11: C-E is the smallest at size 4, Ab-C is next at size 7 (the same size as in equal temperament), and E-G# is widest at size 10 (where 11 would be a full syntonic comma sharp). In my temperament, for comparison, the C-E is size 3, the Ab-C is 8, and E-G# is this same 10. I have no explanation why Lindley and Ortgies have overlooked/omitted the existence of this Neidhardt temperament...or the four others in that same 1732 Neidhardt document that also have an E-G# as wide as (or wider than!) mine. Three of these five temperaments have been readily available in J Murray Barbour's 1951 book (Tuning and Temperament: A Historical Survey), at tables 172, 173, and 175; probably the most popular and widely-used book in the English-language literature about tuning! And, a facsimile scan of Neidhardt's chapters (along with a reliable ASCII transcription) has been available since December 2005 at http://harpsichords.pbwiki.com/Tuning . I myself discussed the features of this particular temperament #11 in public, 6 March 2006, in the HPSCHD-L discussion group where Dr Ortgies is a regularly participating member.... See also Neidhardt's final temperament among this batch, the 3rd-Circle #5. (It is available as the final page of this set of analytical tables presenting all 21 of Neidhardt's 1732 temperaments.) It is a quite moderate temperament all around, where all the major 3rds are of sizes 6, 7, or 8, and therefore it sounds like pseudo-equal temperament. And yet: its E-G# is larger (size 8) than its Ab-C (size 7). This temperament, as well, goes directly against the Lindley/Ortgies assertion: "Neidhardt would never countenance tempering E-G# more than Ab-C." In total, six of the 21 Neidhardt examples published in 1732 break one or both of the Lindley/Ortgies points about the positioning of the note G#/Ab, from E or C on either side of it. Neidhardt saw fit to publish these several temperaments as part of his pedagogical discussion of temperament design strategies (which is a point of his 1732 piece!). In an attempt to refute my work, or at least to cast doubt against it, it simply doesn't do for Ortgies and Lindley to assert that this Neidhardt precedent of an E-G# size (also being wider than Ab-C!) didn't exist; the extant documentation is right here in a facsimile of Neidhardt's chapters, and analyzed in greater detail here. Especially so, as their own assertions are that I've omitted anything that should be important within their epistemology. They volunteered to play defense here against my work, so let's examine their manner of defense, along with the factual (or not!) statements of evidence. Shouldn't they play by the same rules they are proposing to hold me to?

Lindley and Ortgies in their article offer no reaction at all to my five "web supplement" files that are integral parts of the original Oxford article; as if only the on-paper sections of that article are worthy of consideration? I notice also that they haven't engaged any of the technical material from my printed part 2, which has been in print for 16 months (May 2005 issue of Early Music, and downloadable for free here). Their reactions are almost entirely to the presentation in part 1 (February 2005), which is only a small portion of my argument; and which they evidently don't fancy enough to take the rest of the presented argument seriously. They have not acknowledged or engaged any of my 2005 article from Clavichord International, in its clarifications of the material; have they read it? (It's more widely available on the web now, to facilitate any such discussion!) Nor have they offered any musical or historiographical reaction to any of my (or other people's) recordings that use my proposed temperament; isn't this too a dodging of potentially interesting evidence, on their part? (My recordings, too, are freely available as samples on the internet: serving as musical examples that go along directly with my printed analyses. [Harpsichord] [Organ]) To put this bluntly: does my putative Bach temperament actually do what I claim it does, in the music where I suggest it's most relevant, which is the musical and historical hypothesis to be engaged? Without engaging these materials or discussing Bach's music, it seems to me that Drs Ortgies and Lindley are merely picking at my writing style, and my refusal to restrict myself to the only methodological paradigm they will accept. In their roster of "implicit premises" imputed to my work, they have set up a straw-version of my part 1, in isolation: to be knocked down without apparently taking the other sections of the presented argument and evidence into account. I can see that their list of premises is a convenient framework on which their own article is constructed, to organize their material; fine. Still, rather than guessing at my "implicit premises", they could have engaged my publicly stated premises and assumptions that have been available for the record since 31 May 2006. I presented those points directly in a HPSCHD-L group discussion, and I clarified those ideas further through the first weeks of June 2006. But, such discussion has already been going vigorously for much longer than that, since February 2005: with my cards face up on the table, and my open invitations to play and discuss the music (which is, after all, where it matters in playing Bach!). This is all on public record, in the hope that the musical and historical material in my hypothesis might actually be engaged for discussion. Such topics include key characters, the roles of 18th century pedagogy (keyboard and otherwise--dealing especially with 1/6 comma regular and irregular systems!), the measurement of competing temperament systems in Bach's milieu, and Bach compositions (whether inside or outside the WTC) that have always presented special problems of intonation...or any special effects aligning with their vocal texts. But, judging from the range of remarks by Ortgies and Lindley here, it's almost as if I never brought up any of these important issues as important parts of my argument! The whole venture is dismissed as "daft" and therefore outside their consideration. In this long-awaited article by Lindley and Ortgies, I hoped they would address these technical issues of the topic, and take my hypothesis under serious consideration. Instead, though, it appears they've merely offered some (wrong) guesses into my imagination (thereby reducing their own presentation to straw-argumentation), and have dismissed my hypothesis outright without bothering to take all of it into account! In the 16 months since May 2005, they have had plenty of time--and plenty of additional public information from me--to study my published hypothesis carefully, thoroughly, and to construct a much more substantial response/dialogue than this article offers. Why haven't they? Instead, we're treated to merely patronizing barbs such as this one by them (page 6 of this article): "A modern harpsichordist's historical misjudgments are no great moral lapse, however. The music belongs to Dr Lehman just as much as to us and we wish him well in performing it."Um, thanks.

As noted above: my fuller and more tediously heavy-handed comments about all this (and more) will be updated to this space, after their article appears in print. I have another four or five pages of my blathering-on about this, to come in the next month or two. Meanwhile, I have notified the publisher and authors of the factual problems with their tables and their Neidhardt assertions, in the hope that those can be corrected before the print!

My remarks on their final version, November 2006:Their November abstract has changed slightly since October, becoming this:The chain of reasoning in Bradley Lehman's article in Early music, xxxiii (2005), pp.3–23, 211–31, is full of weak links. The notion that Bach followed a mathematical rule when tuning is contrary to relevant documentary evidence that he did not go in for ‘theoretical treatments’ and that ‘mathematizing would never have led to success in ensuring the execution of an unobjectionable temperament’. An expert and musicianly tuner would indeed temper alike the 5ths C–G–D–A–E, but would not feel obliged (as Lehman imagines) to temper some 5ths exactly twice as much as others. The premise that a mathematically rigid tuning-scheme is hidden cryptically in a decorative scroll on the title-page of WTC I is daft, and Lehman's belief that there is only one musically feasible way to interpret this alleged evidence is disproved by the existence of several other such ways besides his (which was based on misreading a serif as a letter). Lehman misrepresents Sorge's account of a certain theoretical scheme from after Bach's death (which he regards as evidence applicable to Bach). No tuning-theorist close to Bach approved of tempering E–G# as much as Lehman does. Lehman's idea that Bach's secret tuning is uniquely beautiful for music by Frescobaldi et al. is outlandish. His one-size-fits-all approach obscures some relevant facts about church-organ tuning in those days. If Bach advised some organ builders about tuning, Zacharias Hildebrandt would be the most likely one, but the meaning of the statement by Bach's son-in-law that Hildebrandt ‘followed Neidhardt’, while clearly ruling out Lehman's scheme, is unclear in some other ways since some of Neidhardt's ideas about tempered tuning changed over the years.The final version was released here on November 10 2006, and in the printed issue as well; download from the Early Music web site. See also the page of errata posted by Dr Ortgies onto HPSCHD-L, November 10 2006, to accompany the release of the article; it is also available at his own web site. Indeed that page of errata acknowledges and corrects the technical points I noted above (my October section here about the table typos, and the Neidhardt E-G# business), ...while not acknowledging this proofreading assistance back to me.... At least they have changed their two unsupportable statements about Neidhardt, explaining their points now with better sentences there! I note several changes in the abstract itself: "Lehman's premise that a mathematically rigid tuning-scheme is hidden cryptically in a decorative scroll on the title-page of WTC I is daft, and his belief that there is only one musically feasible way to interpret this alleged evidence is disproved by the existence of several other such ways besides his (which is based on misreading a serif as a letter). Lehman misrepresents Sorge's account of a certain theoretical scheme from after Bach's death (which Lehman regards as evidence applicable to Bach)."At least this set of small revisions to the abstract acknowledges several things:

Other parts of the abstract and article are similarly problematic, in the way they misrepresent my presented material and my "ideas" and "beliefs", on the way to taking shots at those points. Let me be clear about this: I do not believe that Lindley and Ortgies constructed the straw-man argumentation on purpose, with deliberate intent to mis-represent my statements and my "implicit premises". Rather, I believe it has been a serious and ongoing misunderstanding, where they (probably) started formulating assumptions and counter-arguments even before reading beyond the printed first section of my article. (We must remember, there was a three-month hiatus between that and the printing of the second section: February to May, 2005; and discussions and debates were already loud and heated in various Internet groups before May.) Their first impressions against the thrust of my work were already locked down, ahead of consideration of my entire article, including its web-only portions. They were already casting this off as foolishness, taking my argument as if had little of substance in it beyond speculative graphology. The evidence as I presented in part 2, and in the web-based "Supplementary Data", was not allowed to come into the discussion with much (if any) weight. When it came time to build their counter-argument into an article, they mis-stepped, and it compounded the problem: they did not bother to ask me if their structure (listing their guesses at my "implicit premises", and then concurring with or dismissing each one in turn) made any sense. At least, they could have confirmed with me what I actually said in all of my article, and what I would take to be my own premises, but they didn't. Because they then got so many of those premises wrong, misunderstanding and then mis-representing what I said, point by point, how could it be anything but a straw-man argument? They have been arguing against things I did say, and things I do not believe, all along. Again, probably not deliberately or maliciously! Because they didn't get what my paper actually said, or the evidence I've presented (far beyond graphology), their counter-argument doesn't put up a fair or valid rebuttal. There is more to come here soon, including my notes from playing all the way through the WTC using Lindley's recommended "Bach-style" temperament from this article. The musical/historical point is to find a suitable temperament scheme to play this particular book, isn't it? And since his suggested temperament is presented in the article's Appendix with no given evidence (either within or outside the WTC) for the choices within its intervals, how does it stack up musically against mine that at least uses this WTC title-page drawing (among other things) I've cited as evidence? Ignore the drawing as allegedly non-evidence, label such pursuits as "daft", and then just make up something else...does it work?

The overall thrust of this article's argumentThe presentation by Lindley and Ortgies boils down to the following points:

See also his dismissal of my work as allegedly falling into "the fallacy of sentimens", also November 13, here. He presumed in that posting to speak on behalf of correct scholarship: "It is 'cold' reason, logic and application of scholarly methods which tells us, that Lehman's claim is an unsubstantiated speculation - whether we like his temperament, regard it as useful, or not." ...as if my work doesn't use "scholarly methods", reason, logic, or a dispassionate-enough detachment from the material. Patronizing! He is, of course, entitled to his opinion about that. It doesn't help, though, that his own Early Music article then comes across as anything but dispassionate, and that it falls into variously fallacies of reasoning and logic itself. He and Lindley in their article are the ones presuming to judge such things, by the only viable standards....

The E-G# / Ab-C placement, and Neidhardt and SorgeIn the page of errata posted by Dr Ortgies, he and Dr Lindley have amended two of their article's points as follows: (Page 616) "(b) Neither Sorge nor Neidhardt ever countenanced tempering E-G# (for any reason whatever) by as much as Dr Lehman says Bach always tempered it."...changes to: (revision) "(b) Neither Sorge nor Neidhardt ever countenanced tempering E-G# (for any reason whatever) in actual musical practice by as much as Dr Lehman says Bach always tempered it."And, the first sentence in the next point also receives a change: (Page 617) "(c) Neidhardt would never countenance tempering E-G# more than Ab-C. [endnote 10]"...changes to: (revision) "(c) Nor indeed did Neidhardt ever countenance tempering E-G# more than Ab-C in any tuning that he recommended for use in any kind of social context whatever (i.e. at a court, in a large city, in a small town, or in a village). [endnote 10]" Oh, come on! That is to say: Drs Lindley and Ortgies are willing to deal only with the small sets of temperaments that Neidhardt singled out in 1724 and 1732 specifically for various "social contexts" (their term!); and all the rest of Neidhardt's published temperaments within these same two documents can be fluffed off as allegedly not being for "actual musical practice". How? Why? The E-G# and Ab-C point is not merely a matter of wording a few sentences more carefully, to cover over their assertions where they were caught saying something that is crossed by the published evidence (see my October section, above). It's obviously a play to try to save the skin of their article; but the issue it's more crucial than that, for technical and musical reasons. This placement of the note G#/Ab is fundamentally important to the overall shapes of temperaments, the handling of sharp-based or flat-based music. This is of course assuming a smoothly organized progression around the circle, from this point of placing the G#/Ab at some reasonable position between E below and C above. But, in the context of their argument here, Lindley and Ortgies are simply not willing to engage the possibility of 18th century musicians using a wide E-G# "in actual musical practice" "in any kind of social context whatever"! Their new over-the-top assertions here, while correcting the factual problems of their first versions, make their tone seem even more dismissive in the technical point their article refuses to deal with. My point here is: Sorge (in 1758) and Neidhardt (in several of the 1732 temperaments) both published schemes where this harmonic shape does occur, having E-G# wider than Ab-C. These are documented 18th century formulas, unequivocal in the math. It's Lindley and Ortgies who are tossing these out the window with an allegation that they weren't serious temperaments for actual musical practice, in whatever "social contexts"! These temperaments don't fit into their argument as evidence that they're willing to take as a desirable musical feature; even though this particular Sorge temperament (from 1758) is given as their own Figure 4, right here in their article! Sorge recommended that temperament for use especially in Chorton organs; the performance and improvisation of church music presumably being a situation that is both "actual musical practice" and a "social context". How do Ortgies and Lindley propose to "know" that Neidhardt and Sorge weren't proposing such schemes for real musical use, or that we're supposed to take those as mere speculation, today? Simply because they say so, and we move on as if they've proven it? Their article doesn't establish any rules by which we're supposed to assume that Neidhardt and/or Sorge were joking, or making up merely impractical speculations! Their article tells us only that Ortgies and Lindley themselves will not engage such temperaments that have E-G# wider than Ab-C; and it's a convenient play to dump mine into the rubbish bin, simply by moving the goalposts as they have done. Temperaments with a wide E-G# are outside their penchant to take seriously...and this is propped up with a weak/erroneous claim that Neidhardt and Sorge allegedly didn't take such things seriously either. Nor have they provided any evidence of Bach moving such goalposts, with an opinion one way or the other, or shown how a wider Ab-C is somehow better for his music. Isn't that the point of fashioning credible temperaments for Bach's music, showing how and why the choices of interval sizes are made? By the way, their unchanged phrase "by as much as Dr Lehman says Bach always tempered it" is problematic for another reason, being a straw-man misrepresentation of my article. My article is principally about playing the Well-Tempered Clavier on harpsichords and clavichords, and no such "always" is any central part of my argument. And yet, Lindley and Ortgies seek to knock this down through appeals to organ-tuning treatises, in social contexts where Bach's preludes and fugues were not the music to be played? Ortgies's own hypothesis is apparently that nobody in German-speaking lands at that time played such repertoire in church anyway, under pain of being denigrated as a "paper organist" (i.e. instead of improvising fresh pieces); following that line of logic for the moment, how do organ treatises tell us anything about the WTC, since allegedly that music was not to be played there liturgically? (I must confess that I have personally played parts of the WTC on organs in church services, and have recorded one of these preludes and fugues on the organ to demonstrate how my proposed temperament handles it. Too bad for me, in choosing to do another daft thing as a "paper organist".) Let's summarize this batch of remarks about E-G#, etc. By refusing to take Neidhardt's and Sorge's use of a wide E-G# as musically practical, Lindley and Ortgies are once again simply refusing to engage my argument. Rather, their own assertions about Ab-C needing to be the biggest are (as in Lindley's New Grove articles) simply presented as the only viable game in town, and the refinements are due only to the various sizes of the towns. "Bach-style temperaments" must be pressed into their expectations. They are stuck within that paradigm they've built for themselves! They don't fancy it personally as a historical possibility, and this carefully spun appeal to selective Neidhardt and Sorge material is one of their fallacious arguments set up beside the material: looking like a refutation, but misleadingly so. This is not to allege that they were deliberately being misleading; I believe they are simply unwilling and/or unable to engage my argument from inside the sound of the temperament style being discussed. The design with a wide E-G# is so anathema to them that they refuse to consider this argument with such a "what-if" premise, even hypothetically. Neidhardt and Sorge are then roped in, wrongly, to bolster that refusal. There is even a triumphant bit in this article that Lindley and Ortgies have been able to find "an alternative" reading of the drawing, suiting their own conclusion (well, since it's a foregone conclusion it's really a premise of theirs!) about needing to have a wide Ab-C: "(p 617) (d) One can readily derive from the decorative loops a scheme of temperament in which Ab-C is tempered more than E-G#. The appendix will show this." (p 619, appendix) "In fig. 5 this interpretation is reduced to a musically feasible numerical scheme without involving any gradations finer than half of the arbitrary unit. Here the pattern of relative sizes among the 3rds involving chromatic notes conforms, better than in Dr Lehman's scheme, with the kind of evidence referred to under points (b) and (c) above."Sure enough, the widest major 3rd in figure 5 is Lindley's usual one, and the one he places at lower left in all his diagrams (influencing the way readers might expect it to be the farthest-out from common harmony): namely, Db-F (enharmonically C#-E#), here sizing up at 9 1/2 units. That is merely the same old Lindley argumentation over again, as seen also in his New Grove articles et al, and which I challenged directly in my February 2005 section, thus: "(p 12, February 2005) Unfortunately, the expectation that Db and Ab will be pitched expressively low is one that has been read into the music from Lindley's extensive experience with the basic 'workmaster' shape, and from his own background as a developer of new temperaments within that same paradigm. And it does not necessarily have anything to do with the way Bach himself did organ maintenance, or worked at stringed keyboards. This dictionary entry also has a glaring omission. Where the temperament examples are provided, no temperaments are given that would cross Lindley's observation about the quality of C#-E#. Most remarkably, Sorge's 1758 temperament with the Bachian harmonic shape (see below) would be welcome in the New Grove discussion, at least to show that 18th-century opinion was not unanimous about these shapes. Lindley had included it in his brilliant 1987 article, noting especially Sorge's own assertions about this temperament's suitability for Chorton organs with Cammerton orchestras. Lindley's New Grove assertion about the necessarily worst C#-E# major 3rd therefore comes across as the only possible game in town, and the only thing that really varies is the rusticity index of the town (following Neidhardt's various formulations). In short, the familiar workmaster shape (in various proportions) is presented as the only viable alternative to equal temperament. Temperaments that peak at E major are not judged as presentable."Lindley's argument (back to Early Music, November 2006, now) is just a restatement of his own position, showing no willingness to change it. Temperaments that peak at E major are still not given serious consideration, as historically-feasible alternatives in musical practice. The only "kind of evidence" he'll show us for serious practice is that which suits his own generalization: about Ab-C (and Db-F) needing to be wider than the major 3rds near E-G#. Well: what's to stop Johann Sebastian Bach from having done something that doesn't fit Lindley's and Ortgies's expectations? (Or, for that matter, Neidhardt's or Sorge's expectations either: as in being differently shaped harmonically, or having nothing to do with published court/city/town/village distinctions?) What's wrong with my presented argument, either musically or in the manner a temperament style might be written down, in Bach's book about tuning, except that it crosses Lindley's and Ortgies's expectations? What's to stop Bach from doing something practical, simple, suave, and colorful in his music--as my hypothesis suggests he did? Let's borrow a fine sentence of their own from page 613 of their article: "The '48' are presumably the work of an expert and musicianly tuner. We agree."

Other problems of fallacies, topic-dodging, and tone in the Lindley/Ortgies article

First, it should be pointed out: this article by Lindley and Ortgies doesn't offer evidence that they have tried out my proposed temperament in extant compositions, or in improvisations, for any extended period of practical use. (If they've tried it out seriously, they haven't said so.) As their endnote #15 they offer only an anecdotal remark from a prominent harpsichordist, who didn't fancy attempting it for one particular concert. And, that remark in question was third-hand or fourth-hand hearsay, not a direct quote: I recognize it from someone else's internet posting to HPSCHD-L. The harpsichordist involved, Davitt Moroney, has remarked about that specific anecdote in HPSCHD-L postings on Nov 11 2006 and Nov 12 2006...expressing the wish that Lindley and Ortgies had checked with him as a courtesy before roping him into their endnote.

Also, they have presented no evidence that would refute my hypothesis about Bach's actual practices on harpsichords or clavichords. They merely assert that my procedure is "daft" to use Bach's drawing as evidence ... and then go on to assert a different "Bach-style" tuning of Lindley's own, for which no evidence is given. (That one in particular closely resembles Thomas Young's #1, of 1799/1800, but with the tempering of the naturals relaxed to be less than 1/6 comma. This gives it room for tasteful adjustments around the sharp/flat side of the circle. Why?)

The structure of their article sets out what they call my "implicit premises", in italics, to which they respond. This process is substantially a straw-man argument against my article, since I did not have those particular premises; they have only read them into my work, on the way toward knocking down the ones they don't agree with. I stated my explicit premises, for the record, in May and June 2006 in the public forum HPSCHD-L. These are available in my digest at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~bpl/faq-hpschd.html , or in that list's web archives. I also posted them for easiest reference at the page http://www-personal.umich.edu/~bpl/larips/history.html . Ortgies and Lindley should have had plenty of time between May 2006 and October 2006 to clean up their list of "implicit" premises next to those (i.e. to continue revising their article pre-publication), had they been so inclined....

Here are my remarks about some of those straw-premises (presented here [in brackets]), and about the commentaries on them.

This launches the series of straw-man points, misrepresenting my article on the way to presenting a superior disagreement with it. I did not state anything so strong or bald as that "always the same"; and indeed, my own conclusions in that direction remain tentative (especially as Bach obviously did not have absolute control over the organs he played early in his career; I never said he did). Here is my most relevant paragraph, showing what I actually wrote. This is among a page of my remarks about other specific pieces outside the Well-Tempered Clavier, and showing how this temperament solves the long-standing problems in them: "(page 212, May 2005) Judged from the substantial evidence of his music, did Bach learn, discover or develop his specific tuning method by his early 20s, and continue using it for the rest of his life? I believe it is likely, from the perspective of playability in all his music, and from the inexhaustibly expressive resources of the temperament itself. I understand the dangers of speculating that this temperament might reach far on either side of 1722. But, on hearing how well it works in practice, I see no reason why Bach would ever have discarded such an effective solution for his musical purposes. It allows his music to sound beautiful, richly layered, and continuously engaging through balanced contrasts."To be clear on this: Bach's earlier and later music works so well in the temperament I have derived from his drawing, I am confident that Bach had some method to make that music sound reasonable at the times when he wrote it. It didn't necessarily have to be exactly the same as this; but I believe it was some method(s) allowing his music to be played with pleasing musical effects. Why would any composer, Bach or otherwise, write music that sounds bad on purpose? My contention is that he didn't. In another important distinction here: my context makes it clear that this point was a tentative conclusion, reached after months of studying, playing, listening, and writing. That conclusion was (and remains) surprising to me also, but that's the direction in which I believe the extant musical evidence points ("Judged from the substantial evidence of his music..."). That conclusion has changed the ways in which I approach Bach's music as both musician and scholar. One example (among others) is my suggested purpose that Bach supplied the four Duetti as tuning-test pieces for organs; an idea that I believe is new to the Bach literature. (Hence, my analogy to the "Rosetta Stone": for any willing to follow this musical adventure where it leads, taking this temperament seriously, it can unlock compositions that had seemed difficult to comprehend before. It can also change the way musicians and scholars think about the roles of keyboard temperament within music, being sometimes an integral part of the music and not merely clothing to be applied willy-nilly later...if they're willing to let actual sound be part of musical analyses, not merely treating intervallic relationships from inside an abstract model of equal temperament!) But, what have Lindley and Ortgies done here with this conclusion? They have miscast (or misunderstood) it as a premise ("Bach's tunings of keyboard instruments were always the same"), an overstated premise at that, and one they can conveniently disagree with...since they don't engage much of my material from the article's part 2 or the "supplementary files" anyway.

As I have already presented in my article, the musical reasons for those particular sizes are strong ones: principally the extant 18th century pedagogical materials by Tosi, Sauveur, Telemann, Leopold Mozart and others! (See my discussions of the 55-note division of the scale, which aligns with a general common scheme of 1/6 comma meantone.) I might add several further bits of corroboration: the scaling in the construction of wind instruments to play most easily in this 1/6 comma milieu (which I am exploring presently); and the treatment of this same "equal-temperament size" (i.e. one schisma) by both Neidhardt and Sorge as a theoretically indivisible unit, in practice. Additional corroboration along this line comes from Ross Duffin's new book (© 2007), How Equal Temperament Ruined Harmony (and Why You Should Care). The book presents a historical and practical survey, including an emphasis on 18th-century use of 1/6 comma and 55-division. Near the end, page 149, Duffin encourages modern pianists to experiment with non-equal temperaments, and continues: "The focus of this book, however, has not been on the various keyboard temperaments, but on what non-keyboard performers should do or can do. String players, wind players, and singers all have some degree of flexibility as to where they place the notes of the scale. Their great advantage, as noted again and again throughout history, is that they are not obligated to put the notes--especially the accidentals--always in the same place, but can choose a placement that fits the harmonic context of the moment. Yet, because these musicians must sometimes perform with keyboard instruments, it makes sense for their systems to be somewhat compatible." Certainly, some musicians might prefer some other "intermediate size" intervals on their naturals, instead of a 1/6-comma basis; but (I believe) the burden of proof is on Lindley and Ortgies to demonstrate that Bach would have had sufficient reason to do so. If Bach had wanted something substantially different from a two-to-one ratio of tempering amounts, recognizing them by ear and by wrist action on the tuning pins, mightn't he have found a way to draw his diagram differently? (That's assuming that it is a diagram, of course, which Lindley and Ortgies won't even bring to the table, but simply dismiss as a "daft" procedure.)

My article was quite clear that I believe it's not a mathematical or theoretical scheme by Bach, but rather a practical notation by him of something he used. I presented historical corroboration (chiefly from CPE Bach's report) that Bach did not go in for speculative mathematics! But, what do Lindley and Ortgies do here? They first set up a straw-point that I allegedly believe it's some merely "mathematical scheme", and then they present reports from Mizler and Forkel that would contract this straw-Lehman. I happen to agree with both the Mizler and Forkel quotations, that "Bach did not get involved in deep theoretical treatments of music," and that "mathematizing would not ever have led to success in ensuring the execution of an unobjectionable temperament". Those quotes both do well to support my point that it was a practical/intuitive scheme away from any manner of calculation, and that Bach wouldn't have approached it with any mathematical rigidity! I believe he tuned it by careful musical listening and experience...and then wrote it down in a way that made sense to him, that is, non-mathematically.

I said no such thing; my aim has been merely to present a plausible reading of the drawing that gives Bach the greatest possible benefit of the doubt, i.e. one that sounds colorful, smooth, interesting (admittedly all value judgments...), and solves the outstanding practical problems within his music. This is not principally a mathematical scheme. I believe it is a simple practical process of slightly flattening certain notes at the harpsichord tuning pins, during everyday work. My mathematical presentation merely measures the results, to explain the thing to an expected modern standard of thoroughness! There are no calculations needed to set up this keyboard temperament in practice, but merely a process of nudging the pin a little bit, or approximately twice as much, as indicated by taste and experience. It is easy to do this in under fifteen minutes for the whole harpsichord, by ear. I've been doing it several times a week, for more than two and a half years now. It's not complicated. I have explained all this more fully in an April 2006 article "Bach's art of temperament" available at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~bpl/larips/art.html . By the way, does there exist a distinction between "alleged evidence" and "questionably credible evidence", or perhaps "questionably useful evidence"? Bach's drawing is evidence of something, existing on that title page of the WTC: evidence at least that he took the time to draw it. It's not "alleged" evidence. What are some of the most notable differences (to me) between this drawing and Bach's "decorative" curlicues elsewhere?

But, I have addressed such things in my FAQ pages, almost two years ago already.

I already addressed this point in endnote #63 of part 2, in the original article, printed May 2005. I have also explained it more fully at my FAQ page, early in 2005 and readily accessible to Ortgies and Lindley: http://www-personal.umich.edu/~bpl/larips/faq3.html . The primary reason to read the naturals at that place in the diagram is not because of this putative c, but because the first notes to be tuned are (I believe) the diatonic notes of the C major scale—therefore starting the series with F-C-G-etc. My reading of the diagram would be exactly the same, even if this "small c" were altogether deleted. Again, "Bach's art of temperament" explains this perhaps better than my Early Music article did.

This is the weakest point in the Lindley/Ortgies article: because it is factually mistaken! Neidhardt's 1732 publication includes 21 sample temperaments, illustrating methods by which one may develop them. No fewer than five of these 21 include an E-G# that is tempered as much as, or more than, mine! This document is readily available at http://harpsichords.pbwiki.com/Tuning , both in facsimile and in a reliable transcription.

Neidhardt here begins with a Pythagorean scheme, placing the entire Pythagorean comma in C-G; and the resulting E-G# is a full syntonic comma sharp. He then presents twelve example temperaments in which the 1/12 bits of comma are distributed variously, emphasizing the qualities and varieties of 5ths, "Quinten-Circuls". His next chapter presents the concept of creating temperaments by major 3rds, showing how to work at this experimentally, and it begins with three sample temperaments: all three of which have an E-G# as wide as (or wider than!) mine. He continues with five more practical examples, emphasizing 3rds.

I have already mentioned four of the five here; but the most telling of all is back among the twelve "Quinten-Circuls". It is #11, the one that includes three 5ths of 1/12 comma wide, and has the following most prominent feature: the E-G# interval is the same size as mine, the Ab-C is much smaller (i.e. the same size as in equal temperament), and the C-E is smallest of all. This temperament, even without its four rougher brethren in the same document, sufficiently negates both the Lindley/Ortgies assertions here! Its complete pattern, for the record, is:

C 1 G 2 D 3 A 1 E -1 B 1 F# 2 C# -1 G# 3 D# 1 Bb -1 F 1 C.

The tempering within E-B-F#-C#-G# totals 1 (i.e. 10 out of 11 units sharp, where 11 would be a full syntonic comma). G#-D#-Bb-F-C totals 4 (7 out of 11 units sharp); C-G-D-A-E totals 7 (4 out of 11 units sharp). As noted above, in my section "The E-G# / Ab-C placement, and Neidhardt and Sorge", they have attempted to correct those several erroneous statements to better readings. Those altered sentences merely create different problems, however! And, if they had taken those particular Neidhardt and Sorge temperaments as serious musical resources in the first place, it seems to me they wouldn't have written such dismissive and misleading sentences that needed to be corrected as errata.

This is such a gross overstatement of my position as to be absurd. It's one of the most patronizing barbs and outrageous pieces of straw-man argumentation (among several others) in their article. I did not propose any such thing. Therefore, their gratuitous digs against my alleged taste are both misleading and inconsequential.

Rather, my remarks about 17th century music known to Bach (including Froberger's and Frescobaldi's) were in passing, as I described my process of personally testing my temperament thoroughly...playing through such repertoire to hear what it sounds like (i.e. entertaining the notion that Bach might have done the same). Nor did I use the word "occult" anywhere in my article, or call this temperament a "mathematical invention"; I consider this temperament a simple picture of adjusting notes in practice at a keyboard, not a "mathematical" construction.

Furthermore, there is no reasonable excuse for such presumptive comments against my "aesthetic judgment" or against my own practices as harpsichordist; in e-mail discussion with Dr Ortgies and others in spring 2006 (23 May 2006 on HPSCHD-L), I made it quite clear that I maintain one of my several harpsichords in or near meantone temperaments all the time, to continue to play 16th and 17th century repertoire. Furthermore, one of my own doctoral recitals in harpsichord (1994) was entirely in 1/4 comma meantone, and I still play those compositions in or near meantone because of its appropriateness.

Perhaps they are over-reacting to several of my remarks in the booklet notes of my organ CD set? I wrote the following: "This system turns out to be an excellent tuning solution to play all music, both before and after Bach's. It is moderate enough for complete enharmonic freedom, but also unequal enough to sound directional and exciting in the tensions and resolutions of tonal music. I have chosen the music of this CD set to demonstrate the expressive resources and contrasts available within this system...and of course for the sheer beauty of the resulting sounds on this new organ! (...) Among his many adventures, Johann Jakob Froberger had been a court organist in Vienna from 1637. I chose to record this particular Froberger toccata from 1649 as it is especially wayward harmonically. Liturgically it was probably played with a somewhat quieter registration, in its designated function for communion: but it can also be a wild and exciting piece when played robustly. How were the keyboards tuned, to be able to visit the triads of both B major and A-flat major within a G-Dorian context as here? This composition uses 15 different notes in its course: Db, Ab, Eb, Bb, F, C, G, D, A, E, B, F#, C#, G#, and D#. If Froberger's basic tuning was anywhere near classic meantone (based on pure major 3rds), he either had some split keys on the instrument, or he and his listeners put up with occasionally raucous moments from the enharmonic misspellings." But again, there's nothing here in my remarks to resemble their overstatement, "suits uniquely well the extant music of Froberger and Frescobaldi"; I was simply pointing out that I've recorded a Froberger piece which arguably sounds good on this organ, and which presents problems when played in other twelve-note temperaments!

Well, there are certainly some important things here that Dr Lindley isn't telling us. Since he's brought it up as a topic: that e-mail message from Dr Lindley to me was on 16 December 2005. In it he suggested that such a play-off between the two of us should demonstrate the following three compositions from WTC book 1: the E major, A-flat major, and C major preludes. He continued: "Each of us will have the challenge, as a performer, of making a virtue of the relatively more nervous parts of our respective tunings." I replied to him immediately (19 December) as follows, agreeing that it would be interesting: "For such an occasion, if it ever takes place, I would have to insist additionally on the book 1 preludes in C# major, F minor, and Bb minor. It would seem only fair that each person gets to select the same number of preludes. These three have such prominent spots on downbeats, and often with wide spacing to major 10ths, of the classic problematic intervals. ... One somewhat unexpected thing I have found about my E major, in the Bach repertoire and not only in WTC, is that its sound is especially lyrical in the way it emphasizes smooth melodic motion. Quite the opposite of any 'nervous' effect." At this point, where I had insisted that it should be a fair contest with each person picking half the material for the test, Dr Lindley did not respond any further. He also had the advantage, at that time, of knowing my temperament's layout but without telling me his. Now, having played through the WTC in Dr Lindley's temperament (during October-November 2006) to hear what I'd be up against, I might do even better to select pieces that work even less well in his than the C# major, F minor, and Bb minor preludes! Those are fine examples, to be sure, and would probably be sufficient for such a play-off; but there are some additional problems in (for example) the D# minor fugue, F minor fugue, F# major prelude, F# minor fugue, G# minor prelude, Bb minor fugue, and more. I also don't like the things his temperament does to the simplest keys of all: C, F, and G majors! They're made to be so bland and unresonant.... My own recordings on harpsichord and organ are intended for exactly this sort of comparative listening, putting them next to anyone else's recordings of the same repertoire, and using any temperaments of their own choice. Enterprising listeners can surely come up with some fair "taste tests" in this way, to hear the effects and characters due to temperament. An even better comparison for close listening, of course, is to have two harpsichords side by side, tune both of them by ear in competing temperaments, and then play the repertoire directly on both, oneself. This is in fact what I do all the time, with two harpsichords set up in my living room permanently.

That one is so patronizing to the point of hilarity, I needn't comment further on it.

The material presented in their section here is of course interesting and valuable, but it overlooks a main point: that my article to which they are reacting was primarily about harpsichord practice, and only marginally about organs (principally my remarks about Chorton transpositions).

The passage here is both patronizing and dismissive, while not providing any proof that Bach could not have done anything like this! This "daft" assertion simply indicates that my results and methods do not make credible sense to Lindley and Ortgies. In this same section they present five other ways in which this same "daft" pursuit may be done, allegedly (in their opinions) as well as or better than my proposal; out-dafting me. Their point here, a reasonable one, is that my scheme is not a unique one; but they have already said that earlier in the article, and I never suggested that it was either a unique or unchallengeable reading. My "accounting for all the details" is in my long sections of musical and theoretical analysis. My article was never a mere look at calligraphy; more substantially, it has been rooted principally in musical practices and in methods of 18th century pedagogy. Lindley and Ortgies here dismiss my work as nothing more than unbelievable "tea-leaves" reading (their term!); and they selectively overlook the actual evidence I have presented, which is Bach's music in analysis and performance.

Well, thanks, but that is (once again) overbearingly patronizing in the way it's worded. Let's turn this same patronizing table around and view it from the opposite direction. If Drs Lindley and Ortgies really wish to pursue the sound of my proposed temperament, to hear what it really does in musical practice that they may offer musical reactions to it (even though Ortgies maintains that such a tasteful procedure is non-evidence!), good resources are available. Let them purchase my harpsichord recording of WTC excerpts et al, and Peter Watchorn's complete WTC Book 1, to hear it (if they are not in a position to do primary research on this by playing the whole WTC themselves).

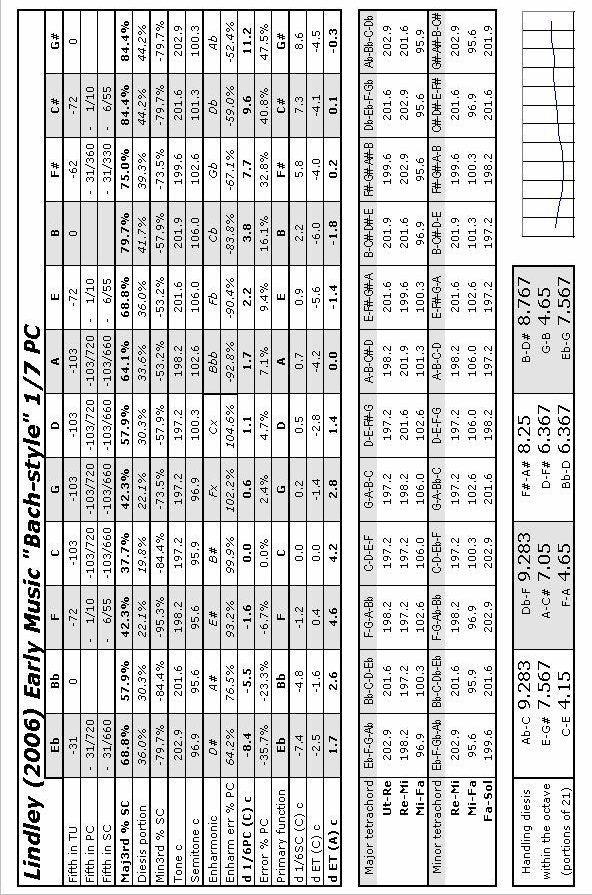

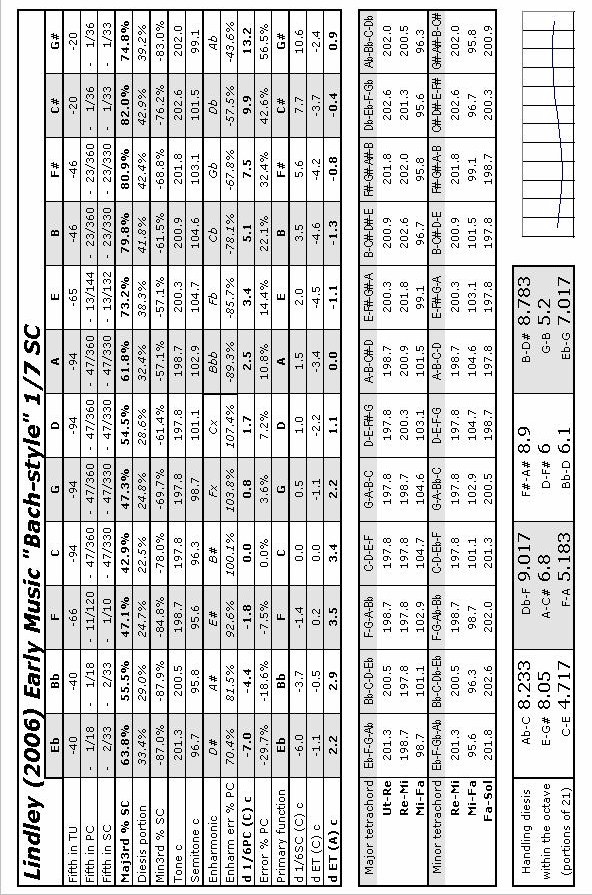

This is all well and good, in practice, presenting a temperament whose overall shape closely resembles Thomas Young's scheme #1 (published 1799/1800), but with a lighter C-G-D-A-E, working out to approximately 1/7 comma each. This gives more wiggle-room around the sharp/flat size to create the types of E-G# vs Ab-C colorations that Dr Lindley asserts are essential. The trouble is that he has not presented any evidence that such a scheme should be "Bach-style", but merely that it sounds "musicianly" and works for him. If he would simply set up, for example, the Neidhardt 1732 "Fifth-Circle #11" as described above, and play through the WTC (as I have done...), listening very carefully...he might come to the same subjective conclusion I have, which is that this particular Neidhardt temperament sounds more "musicianly" and less problematic in the WTC than Lindley's does! Such a test is of course open to anyone who has two harpsichords, or a double-manual harpsichord, plus the tuning and playing skills to go through the WTC: set up Lindley's and this Neidhardt "Fifth-Circle #11" (a clearly-documented and authentic 18th century temperament) for direct comparison side by side, and play the music. What should we do with his assertion that such Neidhardt temperaments were not for practical use? And (a small point), why do Lindley's tuning instructions start from the note E? Where do we (or Bach!) obtain an E tuning fork or similar reference to begin, if we regularly tune our instruments without any electronic aids? Granted, one might start with a standard C fork, build the prescribed E first, and proceed from there...but the printed instructions do not suggest that.

This endnote also wastes space with an illustration showing Kellner's mapping of notes to the seal. So what? I don't stand for Kellner's strings of forced coincidences either, and my article clearly says so; nor is my article any defense of Kellner's outcome (quite the opposite, in fact!) or his methods. Frankly, this endnote by Lindley/Ortgies looks to me to have two main purposes, both being poor sportsmanship:

Come to think of it, why is the Appendix of their article the really substantial technical part of the thing? Why didn't they organize their article so that this discussion of practical temperament (here in their "Appendix") was the main section, and put their roster of straw-Lehman premises into an Appendix--if it even needed to be presented at all?

Playing through the WTC in Lindley's temperamentMy following remarks are from a practical test (October 2006): playing straight through the WTC book 1 in Lindley's proposed temperament, and stopping to jot comments on paper whenever the music sounds harsh or startling. This was done on a Flemish-style harpsichord, tuned carefully according to Lindley's temperament given in the Appendix of this article. Wanting to react only as a listening musician, I deliberately did these playing sessions before venturing into any numerical analysis (see further below).Let it be said, in appreciation, that this temperament already sounds considerably better in this music than Werckmeister 3, Vallotti, Kirnberger 2 and 3, Kellner, Barnes, and some others. On the other hand, that's not saying much! Lindley's temperament merely tames down the same basic problem they have, collectively, which is that the major 3rds B-D#, F#-A#, C#-E#, and Ab-C are too bright relative to the other major 3rds. It also opens up F-A, C-E, and G-B to be less stable than they could be--and this contributes to an overall blandness, plus an inability to settle into richer resonance. Its moderateness is both a virtue and a downfall. Play-through notes, piece by piece:

Now, a small bit of numerical analysis as well, from December 2006: In the major-3rd bounds within Lindley's instructions (the beat rates of his major 3rds at A=440 pitch), it is apparent that his scheme on the naturals captures the range between 1/7 Pythagorean comma and 1/7 syntonic comma, inclusively. Moreover, as I have noticed both in this play-through and in some using various Neidhardt temperaments, there is a liability that is scarcely apparent on paper. This is a phenomenon when playing on harpsichords; organs and pianos behave somewhat differently. As noticed in the natural major 3rds here (F-A, C-E, and G-B: these are the major 3rds of sizes 4 to 5. They hit the "no-man's-land" region between reasonable purity/stability (size 3 or less), and the rapid buzz typical of equal temperament (size 7 or more). That is, they beat rapidly enough to grab extra attention (in musical contexts), but not vigorously enough to turn into an energetic blur--which happens at approximately size 6 and above. Again, this is no number-juggling, but a reaction from listening within ordinary musical contexts, and specifically on harpsichords. Measurements of major 3rds, from size 0 up through 11 and more, might look like simply a continuum on paper; but, there is a region in there (around sizes 4 to 5) where the major 3rds in practice sound especially harsh. I understand that this might look like a paradox, but I encourage any skeptics to listen to this for themselves: major 3rds on harpsichords sound better when they are either smaller than or larger than this rough effect in the middle range! And, this happens to be the range of Lindley's naturals in the three simplest major and minor keys.... [Here's a conjecture, aside: is this phenomenon in part behind the fact that 1/7 and 1/8 comma temperaments make such little appearance in the historical record? Because their resulting major 3rds hit this raw and ugly midrange size, and therefore weren't much worth bothering with in practice?....] Here are examples of Lindley's layout as it works out in practice, interpreted both as 1/7 Pythagorean comma and 1/7 syntonic comma. These are both based on the beat-rate ranges given in his article, at A=440, and worked back to be displayed here as fractions of commas:

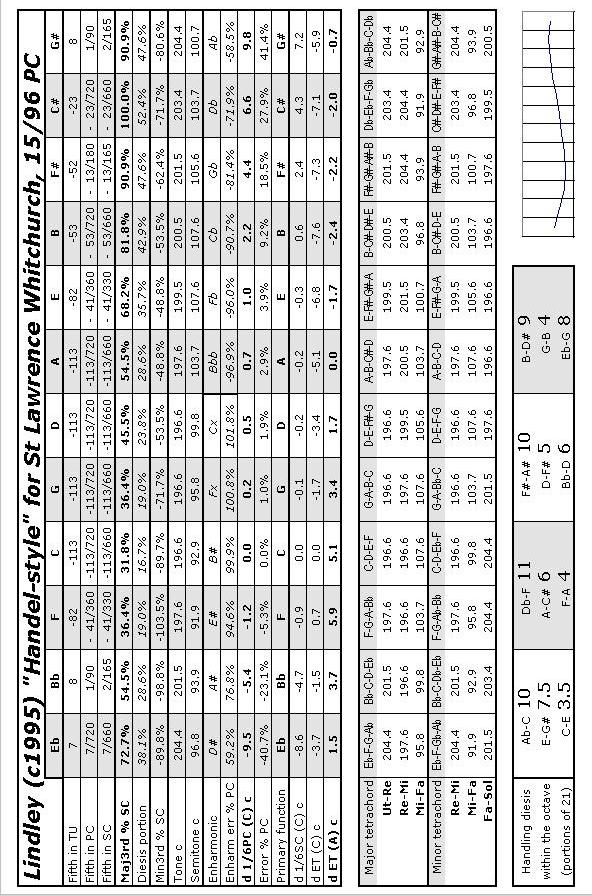

"Bach-style" and "Handel-style" by LindleyCompare the above with the following interesting temperament developed by Lindley, c1995, for the Handel organ at St Lawrence Whitchurch (London suburbs). It also resembles the batch of experimental "Bach-style" temperaments on the last several pages of Lindley's Michaelstein conference article (1994-7).And all of these are seen to be quintessentially Lindley-style, within the algebraic methodology and premises of that Michaelstein article:

I should add: this temperament sounds terrific in that CD set, played on organ in Handel's organ concertos. But also: Handel's music is not as harmonically adventurous as Bach's...so why should there be any expectation that modern temperaments for these composers' music should be of similar shape as one another? The Hyperion booklet doesn't present any of Lindley's reasoning here, either (as the present article about Bach also doesn't). Apparently we're just supposed to take his idealized temperament style as solved, for Handel's music, on faith in Lindley's authority...and if we happen to know about it, on Lindley's algebraic "lucubrations" (his word) at the Michaelstein as well. It still all spins back round to the same set of premises in Lindley's personal preference, by which Lindley is now judging my work to be faulty in that it disagrees with his! Historically based preferences, to some extent, yes; but it has the same leaps of faith that he gives us in his New Grove articles as well. Whatever fits his model outcome, as exemplified in these, is good; and whatever doesn't fit is wrong. Also of interest, at least to me, is the relative sizes of Lindley's naturals here for Handel. They are basically 15/96th PC until we get to the F and E endpoints, each spread out a little wider; that is, they are tempered at a size between 1/6 Pythagorean comma and 1/6 syntonic comma (i.e. about 11/72 PC). This same tiny region in between 12/72 PC and 11/72 PC is where the regular 55-division of the octave also lives. So essentially, Lindley has put his "Handel" naturals onto the 55-division spots described by theories of Tosi, Sauveur, Telemann, Leopold Mozart, et al. I agree! (And so do Thomas Young's two temperaments of 1799/1800.) All hair-splitting aside, anything in this little region bounded by 12/72 PC and 11/72 PC is historically plausible, to me, for the regular tempering of the naturals. It's Lindley's treatment of the five sharps/flats that I don't agree with. They're probably OK for Handel, but they're not high enough for Bach's music.

Ortgies's further commentary on his web siteAs of November 5th 2007 (and probably considerably earlier), Dr Ortgies's errata and corrigienda page for his article has the following two paragraphs introducing the piece:In it we discuss some of the historically wild and methodologically wrong speculations published last year (2005) by Bradley Lehman in his article in Early Music (Note 1), where he claimed to have discovered "Bach's temperament."That's sort of amusing, as their article doesn't say anything about Sparschuh playing a practical joke at Kellner's expense...or about any of the 7/7/77 and 9/9/99 number games. If this were important, why didn't Ortgies and Lindley put it into their article? I didn't "know" about it until today, reading it there on Ortgies's page. 1977? Really? I'd always followed Kellner's words from one of his articles, or maybe it was Kellner's web site, claiming that he figured it out during the week of Christmas, 1975. But we digress. Nor does their article explain what is meant here by "historically wild" and "methodologically wrong" in assertions against my work. Wow. Window dressing. And, Ortgies's page has links to "Full text" and "Full text (PDF)" of their article...but those links work only for paid subscribers to the journal. Since they're not giving away what they actually wrote, the errata and corrigienda and the abstract will have to serve some of their readers who will see only those bits instead of their article. Hmm. My work is all downloadable for free as a courtesy services that Oxford provides to all their authors: a toll-free link for use on an author's own web site, for promotion of the work. Why haven't Ortgies and Lindley availed themselves of their free links, to bring their arguments before the general public?

November 2008: Lindley has a short bit of correspondence published in the current issue of Early Music. It includes this sentence: "I think it was kind of Ortgies to omit from his review any mention of Duffin's endorsement of the notorious idea that Bach had a secret mathematical formula for tempered tuning which he conveyed cryptically in the decorative loops of the title-page of Part 1 of the '48'." Yes, that would indeed be preposterous and far-fetched, especially because Bach did not go for any "dry, mathematical stuff". A secret mathematical formula, encrypted? It shows that Lindley is (after more than three years) still stuck in his own straw-man argument where he apparently doesn't understand a main point of my article! I never said it was any "mathematical formula", secret or otherwise; nor did I say Bach was being cryptic with it. Bach's drawing, in my opinion, is a straightforward and practical diagram to get the work done without any calculations. Nor do I require Bach to have understood anything in theory about commas, or mathematical constructions. To me, the loops in Bach's diagram indicate a simple narrowing by "double" or "single" amounts from a pure 5th, by experience and listening, not by any secret or overt mathematical process! The thing takes less than three minutes to do, accurately enough in practice, sitting at a harpsichord with a tuning lever. How difficult is that point to understand? Perhaps Dr Lindley (if he ever sees this web page that rebuts his preposterous published comments) should take a look at my lecture notes from 10/22/08. In that presentation I explained the theory without requiring the audience to do anything mathematically difficult, or even to read music. I showed how the principles arise from the necessity of playing more than two dozen differently-named notes within that book of music, Das wohltempirirte Clavier. I demonstrated the easy hands-on process of tuning, without requiring Bach or anyone else to calculate commas. The presentation didn't go into "the little C capitalization stroke" that was such a red herring to both Lindley and Ortgies, among others; Bach's tuning sequence (according to my analysis) requires the same placement of C whether or not that little stroke is taken as part of it! Are there any other silly little points of contention that are still tripping up Lindley and Ortgies from understanding the work they're trying to criticize?

August 2009: In Mark Lindley's review of Patrizio Barbieri's book Enharmonic instruments and music 1470-1900 ('A great microtonal survey', Early Music, xxxvii/3 (2009), pp.481–3), there is this sentence: "The section on 12-note equal temperament includes a page and a half on this other topic (with an appropriately dismissive footnote about Bradley Lehman's hypothesis regarding Bach's use of an unequal circulating temperament)". [2011: A free version is now available here through Stanford's "HighWire" service.] For response, see November 2009, below.

November 2009: Early Music, Bradley Lehman: "Unequal temperaments circulate again" letter to the editor, Early Music. A call for reasonable and valid argumentation in the field of temperament research - especially from Lindley, whose published remarks in that journal have now mis-represented my work three times. I still do not believe he is doing that deliberately; rather, it seems to me that he misunderstands the thrust and the evidence of my whole argument, and he is still arguing against (and belittling) that underestimation of it. The letter is printed and published online in Early Music (Oxford University Press), February 2010, Vol 38 #1, p 170-171. [PDF] [HTML] It had been accepted for the November issue, but the entire Correspondence section was then delayed until February.

|

v Introduction v Articles v FAQ v Practice v Theory > History - CPE Bach * Lindley/Ortgies - O'Donnell v Etc v Recordings |