© Bradley Lehman, 2005-22, all rights reserved.

All musical/historical analysis here on the LaripS.com web site is the personal opinion of the author, as a researcher of historical temperaments and a performer of Bach's music.

Johann Sebastian Bach's tuning Welcome!

Welcome!

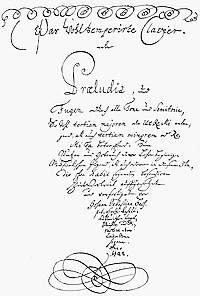

Let's begin. It appears that Johann Sebastian Bach notated a specific and unequal method of keyboard tuning. He did not express it in our normally-expected modern formats of theory, or numbers. Rather, he drew a diagram that looks like a practical hands-on sequence to adjust the tuning pins, working entirely by ear. The music constrains any solution to be nearly equal temperament, and then, the diagram's irregularity shows how to shape the desired subtle inequality. In my simple interpretation, it keeps the six main notes of the C major scale (C, D, E, F, G, A) in evenly-spaced positions, at their normal spots within the context of late 17th century practice. The tuner is then to install the keyboard's six remaining notes (B and the sharps F#, C#, G#, D#, A#) in tastefully raised positions, with adjustments as indicated by the diagram, so they can also serve well as flats. This process of minimal but necessary compromises makes the keyboard ready to play music in all 24 major and minor scales. Every scale has a subtly different expressive character, as the steps are not all exactly the same size. The harmonies have various tensions and spice, when the notes of the scales are built together into chords. Bach demanded and exhibited a system of this enharmonic flexibility not only in the diagram, but also through the music in Das Wohltemperirte Clavier. It presents his tuning challenge (and gives the solution!), where most of the preludes and fugues each require the smooth handling of more than 12 notes. For example, his D major prelude and fugue use all of Bb, F, C, G, D, A, E, B, F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, and E# in the same piece: 14 notes. Some of the other pieces require 13, 15, up to 25! The last piece in the book, the B minor fugue, requires 17 (Eb up to Fx), and presents 13 of them as early as the subject: six naturals C, G, D, A, E, B, and seven sharps F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E#, and B#. Bach obviously knew how to set up his keyboards appropriately before writing his music for them. The aim is to restore the specific intonation scheme of his everyday keyboard tuning, the sound relationships he expected to hear in his melodies and harmonies, as they may have influenced his creative imagination. By hearing how these musical elements work through composition and improvisation, we gain new clues into the interpretation of Bach's music: affecting at least the areas of articulation, phrasing, dynamics, timing, intensity, and drama. The tensions and resolutions within the music suggest fresh ideas in performance, both through intuitive reactions and through close analysis. The resulting temperament has been absent from our history books. It was lost under layers of assumptions and habits that have led away from it. I believe that the particular sound of this temperament, as an integrated part of musical practice, has profound implications for all of Bach's instrumental and vocal music that uses keyboards: either with written-out parts or in the basso continuo. Since every scale has a different Affekt or mood, from the different musical tension within the intervals, the music sounds colorful and "alive" as it moves. Bach's music itself is a large body of primary evidence for temperament: sounding convincingly brilliant and expressive when the intonation is right, or rough and ugly in temperaments that don't properly solve the enharmonic problems. This "LaripS.com" web site clarifies and explains the published papers, both through theory and practice. It provides various introductions to this work, for different levels of readers' interest. It serves as an archive of ideas as this temperament is used and discussed among musicians, researchers, and enthusiasts.

The necessary background: understanding "ordinary" tempering methodsKeyboard temperaments are built from a principle that is sometimes called "meantone": within whatever size a major 3rd is, the tone (whole step) is at the mean (average) position. For example, within the major 3rd interval of C-E, the D is placed at the mean point where the steps C-D and D-E are the same size as one another. In practice, when tempering a keyboard instrument by ear, this is done by tuning a sequence of 5ths, and narrowing each 5th slightly by the same amount. (C-G-D-A-E-B-F#-C#-G# sharpward, and C-F-Bb-Eb flatward.) The resulting layout is regular, or equally-spaced. Depending on the amount of narrowing that was given to all of the 5ths, these regular or meantone temperaments have various musical properties.

Furthermore, the sharps and flats do not connect with one another by 5ths. Somewhere, typically at G#-Eb or at D#-Bb, there is a diminished 6th that is considerably wider than the regular 5ths. Any intervals played across this enharmonic gap sound rough and out-of-tune, both harmonically and melodically, because some of the notes are being misinterpreted with wrong enharmonic spelling. Those notes are missing from the scales. To be able to handle the enharmonic requirements of the music, the musical spelling of the notes for their scales and harmonic intervals, there are several ways to get through those problems with regular temperaments:

Already by the 17th century, much of the extant music calls for the exotic notes such as D#, A#, E#, B#, Ab, Db, Gb, Cb, and/or Fb. It is also common to find enharmonic pairs (such as A# and Bb) both needed in the same composition. The problem gets more extreme with Bach's music, even his earliest, and that of the musicians around him: so frequently needing more than 12 named notes within a single composition that any old-style regular temperament was not feasible. The music itself tells us which notes it needs, in finding a satisfactory tempering scheme to play it. Where the choice is to derive an ordinary or irregular layout, the careful listening and adjusting at a keyboard can be summarized into process flowcharts.

After the hands-on adjustments of pitch are made, and tested thoroughly in the music to be played, the resulting irregular temperament can be written down. This makes it easier to reproduce accurately on other occasions, so one does not have to solve the same problem of tasteful adjustments again every time. That, I believe, is what Bach did here: through a hands-on "ordinary" process of listening to and adjusting the scales, he (or someone around him) found a very good irregular layout that solves all the musical problems. It allows one to play beautifully in all 24 major and minor scales, while it also keeps the most acoustically-favorable sounds in the most commonly-needed scales. It provides enough contrast that every scale sounds subtly different, which can make the music more exciting and interesting as it modulates. He then wrote down enough details, a picture of the tempering result, to show how to do it again.

The recipeThe way I believe Bach himself explained it to experienced harpsichord tuners by ear, step by step, with (or without!) his diagram:

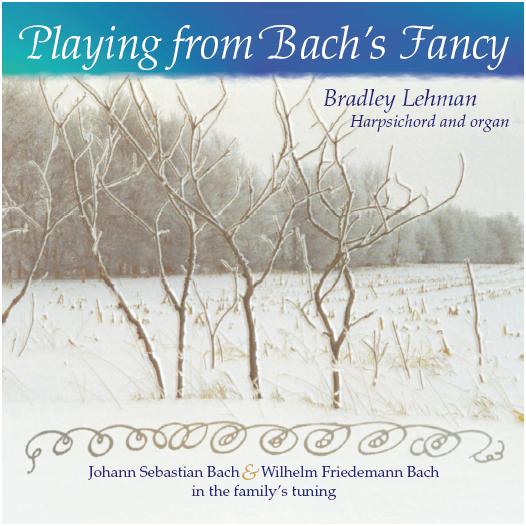

ArticlesMy main scholarly article proposing this reading of the evidence is published by sections in the February and May 2005 issues of Early Music. That article, "Bach's extraordinary temperament: our Rosetta Stone", describes the historical context and provides musical and mathematical analysis. [Outline, and free download of its seven PDF files from Oxford University Press]A supplementary article "The 'Bach temperament' and the clavichord" is available in the November 2005 issue of Clavichord International. It contains further discussion of practical issues: some specifically for clavichord, some more generally in analysis of Bach's keyboard music, scale structure, enharmonic considerations, and by-ear tuning instructions. The compositions presented include BWV 772-801, 802, 808, 849, 887, 988, 1079, and 1080. [Outline] [Full text] A November 2005 essay "The Tuning" gives a two-page summary of the temperament and its musical character. [Full text] It is printed in the booklets of Peter Watchorn's CDs. The 2006 article "Bach's Art of Temperament" for BBC Music Magazine further explains this temperament from several additional practical angles, focusing especially on the blend of the C major and B major scales. (C, D, E, F, G, A, B; B, C#, D#, E, F#, G#, A#) [Full text] The BBC's version was shortened and given the title "In Good Temper". Other articles about this temperament are listed here. There is also a page of my responses to other people's articles and books where they present their agreements or disagreements with this temperament. My October 2008 lecture notes for James Madison University turn out to be almost a complete article, in themselves. In Early Music November 2009 I have a letter to the editor, calling for fair argumentation on this topic...especially from Mark Lindley, who has mis-represented and disdained my work three times in that journal. In "Unequal Temperaments", The Viola da Gamba Society Journal vol 3 part 2 (2009), 137-163, I review a 2009 book by Claudio di Veroli. I also address some recent argumentation about Bach keyboard temperament, and debunk the 1979 analytical methodology of John Barnes. [PDF] See also the lecture notes from October 2010, a presentation at the University of Colorado: "Recovering Bach's tuning from the Well-Tempered Clavier". These give a deeper perspective on the technique of examining which notes are used in various compositions, and the way that that process informs the inferences about temperament. My Autumn 2022 article, "The Notes Tell Us How to Tune", revisits the scale theory and the enharmonic measurements from the 2005 article. It explains everything again after the intervening 18 years since 2004, written from a musical scale perspective. I set for myself the challenging task of describing all the principles using as little math as possible.

Quick start!

Easy way to tune it accurately and mostly electronicallyIf you prefer not to tune by ear, and not to have to count any beats anywhere, do this:

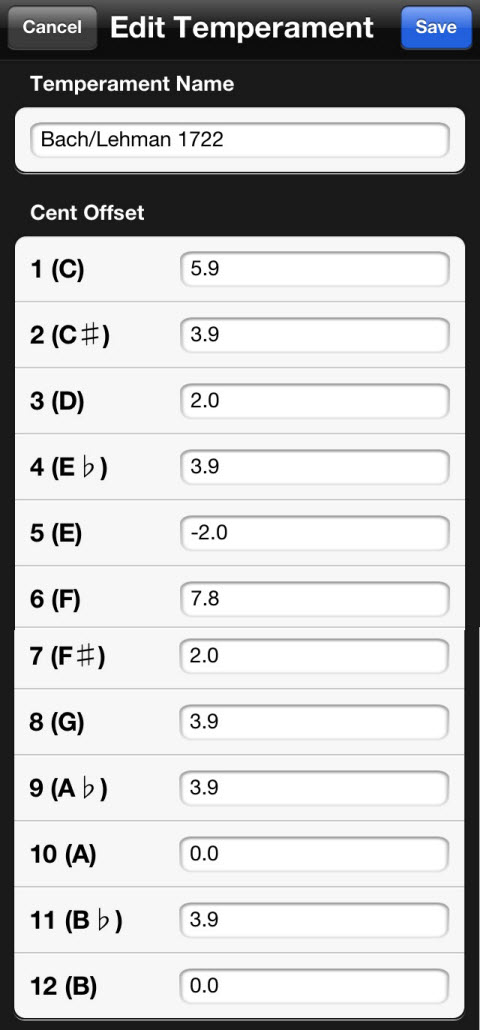

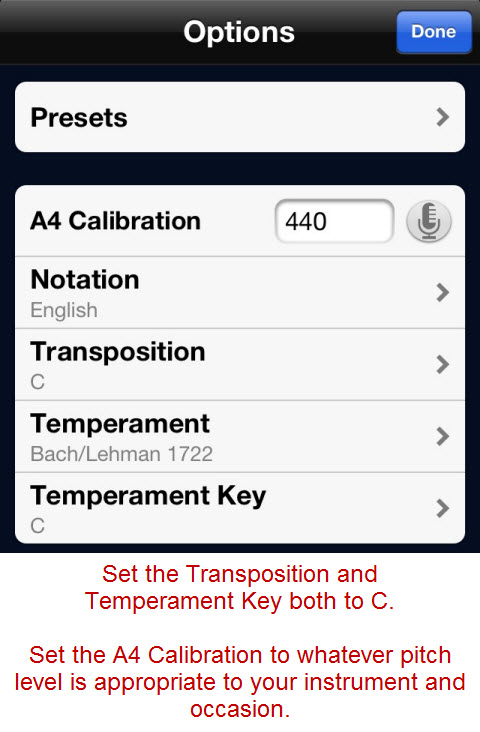

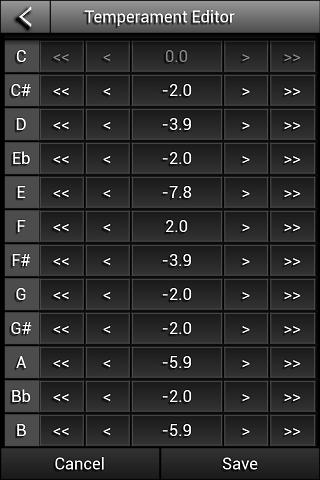

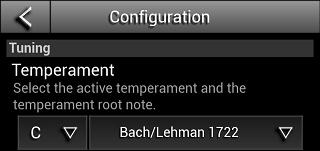

Offsets for ClearTune, PitchLab, and other electronic tunersIf you use an app or device that allows definitions of Custom temperaments, such as ClearTune, set it up with the following cent offsets from equal temperament:C (+5.9), C# (+3.9), D (+2), Eb (+3.9), E (-2), F (+7.8), F# (+2), G (+3.9), G# (+3.9), A (0), Bb (+3.9), B (0). Check it all by ear, as described in the above section. You should have an even and smooth F-C-G-D-A-E (all with the same quality as one another, 1/6 comma narrow), a pure E-B-F#-C#, and a very gently wavering C#-G#-D#-A#. The Bb/A# should be placed at a spot very slightly lower than the spot where it would have been pure from both D# and F. When setting the octaves, check all the 5ths and 4ths by ear for appropriate quality. This habit is especially useful when working on the treble.

For the PitchLab tuner, which is newer (2014) and better than ClearTune, do the following:

See also this review of PitchLab by Paul Poletti.

Audio samples and video demonstrationsThere are pages of recorded musical examples and 20-minute playlists of streaming audio, with performances by Bradley Lehman on harpsichords and pipe organs.....More than a dozen recordings by other musicians using this "Bach/Lehman 1722" temperament: on harpsichords, fortepianos, pipe organs, digital organs, synthesizers, and more.... A survey of the temperament's use in public performances and recordings by hundreds of musicians, and built into pipe organs and other instruments.... The LaripS Recordings label.... There is a growing collection of video demonstrations, showing how to tune harpsichords by ear in this and several related temperaments. Other resourcesIntroductory lecture at an informal level.... (How to explain temperament, and why it matters, to teenagers!)

A historical survey of other "Bach" temperaments as hypothetical reconstructions.... Additional resources for music theory, practice, and history....

All LaripS.com contents © Bradley Lehman, 2005

Improved graphics supplied by Joakim Bang Larsen (Norway), 5-Apr-05; thank you!  |

* Introduction - Features - Lecture - Background - Videos v Articles v FAQ v Practice v Theory v History v Etc v Recordings |

In these regular temperaments, however, the sharps and flats are not interchangeable. The only available notes

are Eb-Bb-F-C-G-D-A-E-B-F#-C#-G#, or occasionally substituting D# for Eb. Where the keyboard has been tuned

with a regular Bb, that pitch will sound wrong when played in scales, melodies, or harmonies as if it were A#.

The Bb is tuned too high to be A#. Similarly, F is too high to be played as E#, B is too low to serve as Cb,

and this problem continues into all other enharmonic spellings of the notes.

In these regular temperaments, however, the sharps and flats are not interchangeable. The only available notes

are Eb-Bb-F-C-G-D-A-E-B-F#-C#-G#, or occasionally substituting D# for Eb. Where the keyboard has been tuned

with a regular Bb, that pitch will sound wrong when played in scales, melodies, or harmonies as if it were A#.

The Bb is tuned too high to be A#. Similarly, F is too high to be played as E#, B is too low to serve as Cb,

and this problem continues into all other enharmonic spellings of the notes.